It's Raining Fish and Spiders (8 page)

Read It's Raining Fish and Spiders Online

Authors: Bill Evans

2

Hurricanes

Hurricanes: Monsters of the Tropics

Hurricanes are the extreme-est of the extreme! Their winds and waves have wiped out entire communities worldwide and have changed coastal landscapes all over the planet. Hurricanes are the deadliest of storms with more than 20,000 American lives lost in the last 150 years. In a single year, as many as eighty-five hurricanes can prowl across the earth.

A hurricane is a gigantic machine, a tremendous latent heat pump, which can produce violent winds, incredible waves, torrential rains, tornadoes, and tremendous amounts of flooding.

What we call a hurricane is really a tropical cyclone, which is the generic term for a low-pressure system that generally forms in the tropics. The winds of a hurricane swirl around a calm central zone called an

eye

, which is surrounded by a band of tall, dark clouds called the

eyewall

. Pressure changes around the eyewall create the hurricane's strongest winds.

A washed-out bridge in the middle of a flood

U.S. Geological Survey/Department of the Interior

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Department of Commerce

When these storms happen over the northern Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, or the northeastern Pacific Ocean, they are called hurricanes. The word “hurricane” comes from “Hurican,” the Carib god of evil. Hurican was derived from the Mayan god, Hurakan, one of the culture's creator gods, “who blew his breath across the chaotic water and brought forth dry land.”

In other parts of the world, hurricanes have different names depending on where they occur. In the northwestern Pacific Ocean they are called typhoons. When their wind speeds exceed 150 mph they are called super typhoons. In the southwestern Pacific and southeastern Indian oceans they are called severe tropical cyclones; in the northern Indian Ocean they are called severe cyclonic storms; and in the southwestern Indian Ocean they are called tropical cyclones. Whew! That's a lot of descriptions from around the world. Sometimes you need a scorecard to keep up in this game!

Hurricanes are also the only natural disasters with their own names. Camille, Wilma, Charlie, Andrew, Hugo, Katrinaâeach seemed to have a personality and each caused a different sort of disaster.

Hurricanes are very special. A tornado can have winds up to 300 mph, but a hurricane is rarely above 155 mph. A tornado, however, is a very concentrated event compared to a hurricane. A tornado may be more violent, but hurricanes are more deadly! As you will see in this section, hurricanes

make

tornadoes!

A mile-wide tornado is huge, but a 100-mile-wide hurricane is considered small. Few tornadoes last an hour, whereas a hurricane can last for weeks, producing 12 to 20 inches of rain and flooding hundreds of miles of coastline with 20- to 30-foot-high storm surges.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Department of Commerce

Despite improved weather forecasting of hurricanes, loss of life and terrible destruction continue to occur. This was never more evident than in Louisiana and Mississippi in August of 2005, when Hurricane Katrina caused the deaths of 1,836 people and the destruction of hundreds of thousands of homes and other buildings.

Hurricanes generate an incredible amount of energy. In one day, an average hurricane can produce the equivalent of 200 times the total amount of electricity that can be produced worldwide! That's an incredible amount of energy! Imagine if we could capture or harness that energyâwe would never have to rely on fossil fuels again.

Fortunately, only about 3 percent of that energy is converted into wind and waves. I say

fortunately

because if all of that energy were converted to the surface landmass, it would have the destructive impact of all of the nuclear weapons of the United States and Russia put together!

Ingredients for a Hurricane

The ingredients for a hurricane are simple, yet the formation of a hurricane is a complex process. The key ingredient for a tropical cyclone is a little wind and some warm ocean waterâ82°F (28°C) and above. Add a humid air mass and weak upper winds flowing in the same direction as those on the surface of the ocean, and you have the perfect environment for a tropical cyclone, especially if the surface winds are rotating.

Frank Picini

Preexisting weather disturbancesâlike thunderstorms moving across from western Africaâcan interact with rotating surface winds, a rising humid air mass, and higher-level winds fto create a tropical cyclone.

This sort of encounter takes place fairly often, but thankfully, only a few of these disturbances become full-blown hurricanes! I can watch the satellite loops all season long and see hundreds of these situations develop, but usually just a handful will have winds of above tropical storm strength at 39 mph!

The warm water must be at least 200 feet deep because as the storm develops, it forces energy into the ocean, which brings cold water up from the depths below.

Winds must be converging at the surface and the wind must also be unstable so that the growing storm will rise. The air must be very humid and go very high into the storm system (as high as 18,000 feet) as the extra water vapor supplies more energy.

To avoid ripping apart the developing storm, all existing winds should be coming from the same direction and at nearly the same speeds. Finally, an upper-atmospheric high-pressure area must exist above the system to pull away the air rising through the storm. This will help the storm to grow stronger.

I think you can understand now why only 10 percent of tropical disturbances grow into tropical storms. The combination of the right ingredients, coming together in the right conditions at the right time, is extremely rare!

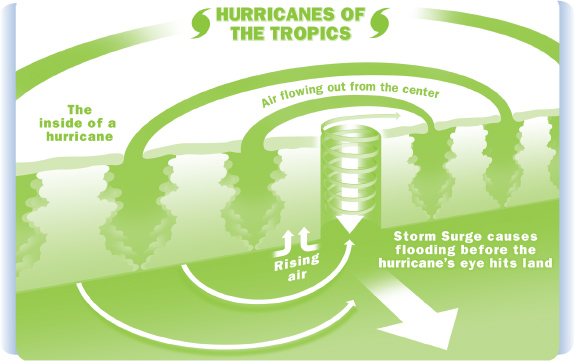

Structure of a Tropical Cyclone

The formation of a tropical cyclone is also a process. First, thunderstorms grow and combine, creating a disturbed area in the tropics. Then warm humid air spirals inward as the thunderstorms organize into a circle or a swirl. Next, bands of thunderstorms spiral around the center. Hurricanes are made up of these bands of thunderstorms, called rain bands or spiral bands. They can be 3 to 30 miles wide, and 50 to 300 miles long. The spiral bands contain all of the destructive winds and flooding rains of a hurricane.

Frank Picini

The most recognizable feature of any hurricane is the eye. This is an area, 10 to 40 miles in diameter, around which the entire storm rotates. In the eye, the skies are clear and the winds are light. It's the calmest part of the tropical cyclone, the area where the lowest surface pressures are found.

A hurricane's eye becomes visible when some of the rising air in the eyewall is forced toward the center of the storm from all directions. This convergence causes the air to actually sink in the eye. This creates a warmer environment and the clouds evaporate, leaving a clear area in the center.

Air flowing out from the center of the storm begins curving clockwise as water vapor in the air forms cirrostratus clouds, which cap the storm. As the storm approaches the coast of a landmass, a huge mound of water builds to the right of the eye. This is called the

storm surge

, which is discussed further later on.

These monster storms capture our attention because of their power and their destructive capabilities, as well as their impact on the economy and on our society.

How Water Powers a Hurricane

As I mentioned, a warm ocean and warm air are the key ingredients in a hurricane. The warmer the air, the better. Some of the largest and most destructive hurricanes of all time, like the 1938 hurricane called the “Long Island Express,” and Hurricane Camille in 1969, occurred during years in which there was record heat.

Warm seawater evaporates and is absorbed by the surrounding air. As humid air rises high into the atmosphere, water vapor condenses into water drops. When that happens, heat is released. This is called

latent heat

âremember, earlier I described a hurricane as a latent heat pump. That latent heat warms the surrounding air, making it lighter and causing the air mass to rise even more. As the warm air rises, more air flows inward to replace it, causing wind.