It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War (10 page)

Read It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War Online

Authors: Lynsey Addario

Afghan women shield their faces at the women’s hospital in Kabul, May 2000.

On one of my last days there, I visited with a Sudanese woman named Anisa, who ran the main UNHCR office in Kabul and had been living in Afghanistan for several years. I was relieved to see her, sitting behind a grand desk in a bare-bones office. I had been craving the presence of a female with whom I shared at least a few cultural references.

Anisa took me to a middle-class neighborhood on the outskirts of Kabul. Four women greeted us at the door. The front of their blue burqas had been slung back over their heads, revealing angular features, fair skin, and striking blue eyes. They all wore floral skirts. Their white patent-leather pumps were lined up at the door. It still surprised me to see an actual living being under the tomblike burqa. They smiled warmly and excitedly ushered us inside their modest clay home, wicker baskets and pink-and-green-embroidered sheets hanging on the walls, lacy curtains fluttering by windows covered in wax paper.

The UN had secretly hired the women to teach vocational skills—knitting, sewing, weaving—to widows and poor mothers in their neighborhood. They sat on the floor and, over the requisite tea and biscuits, began to talk. They were nothing like the women of the countryside; they were educated and had held jobs in government ministries before the Taliban came into power. They were frustrated with the restrictions on their freedoms, which, among other things, prohibited them from working outside the home.

“Before, our capital was destroyed,” one of the women explained. “The Taliban has rebuilt our capital. In each house in Afghanistan, though, the women are the poorest of the family. The only thing they think of is how to feed their children. Now the men are also facing problems like the women. They are beaten in the streets if their beards are not long enough, thrown in prison for not praying. It is not only the women who suffer,” she said.

“Wearing a burqa is not a problem,” another said. “It is not being able to work that is the problem.”

Everything they said surprised me. It had been naïve of me to think that, given all the repression women in Afghanistan were facing—their inability to work or get an education—wearing a burqa would be high on their list of complaints. To them, the burqa was a superficial barrier, a physical means of cloaking the body, not the mind.

The women also put my life of privilege, opportunity, independence, and freedom into perspective. As an American woman, I was spoiled: to work, to make decisions, to be independent, to have relationships with men, to feel sexy, to fall in love, to fall out of love, to travel. I was only twenty-six, and I had already enjoyed a lifetime of new experiences.

• • •

T

HE DAY BEFORE

I left Kabul, I returned to the Foreign Ministry to get my exit visa from Mr. Faiz.

“Welcome,” Mr. Faiz said, gesturing for me to sit. “How was your trip? What are your impressions of our country?”

I thought of Mohammed from the visa office, the working city women stuck at home, the widows in the countryside, the maternity hospital with its ghastly conditions. Mr. Faiz, in his grand office at the Foreign Ministry in Kabul, represented everything millions of women across the world have fought. In Afghanistan the Taliban granted me license to see and to do things no Afghan woman had permission to do since they took control: partake in meals and in conversations with men outside of their families, go without a burqa, work. But perhaps there were many women in Afghanistan happy with how they lived: their days spent baking bread in the countryside and caring for their families in the crisp, clean Afghan air. My own life choices must have been equally as confounding to people like Mr. Faiz.

“Mr. Faiz,” I said, “I love your country. I only wish Taliban rules permitted foreigners like myself to openly engage in conversation with the locals. It is very difficult for me, and for journalists, to visit Afghanistan and have anything positive to write about, given such restrictions on our interaction with the Afghans.” Mr. Faiz, of course, didn’t know I had broken their rules by meeting with some Afghans on my own. “It is a culture renowned for its hospitality and warmth.”

“I understand,” he said.

I looked down at the last sip of room-temperature green tea in my china cup and felt oddly comfortable. I didn’t want the moment to end.

“It is not time yet. When we are ready to have you meet with our women and our people, we will definitely invite you in.”

I smiled, and as our eyes met Mr. Faiz did not look away. I finished the last cup of tea, and as I left I pulled my chador tightly around my head and neck, making sure it wouldn’t slip from my hairline in the wind.

I returned to Afghanistan twice in the next year. Between trips I found a photo agency willing to distribute my work. But for a long time no newspaper or magazine bought them. In the year 2000 no one in New York was interested in Afghanistan.

CHAPTER 3

We Are at War

I returned to New Delhi and kept shooting, traveling throughout India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nepal, focusing on human rights and women’s issues. Marion and I fueled each other with story ideas and motivated each other when we were tired or frustrated or in a rut. It was also easier for us to get assignments as a team, so when Marion decided to move to Mexico in 2001—because she had always wanted to live in Latin America, and she and John had broken up—I did, too. It was on to the next adventure.

I never considered going back to live in New York and didn’t even stop home to see my family. By the time I finished college, my family had scattered across the country. My sister Lauren moved to New Mexico to paint when I was still in high school. Lesley moved to Los Angeles to work for Walt Disney when I was in college, and Lisa followed a few years later to write movies with her partner. Christmas became our time to gather as a family, a reunion we all looked forward to.

We remained close despite the geographical distance, but life abroad had its costs. While I was in India, my sister Lauren’s first husband was diagnosed with lung cancer and died thirty days later. I never got to say good-bye to him or comfort her. That same year my mother was in a car accident that left her unconscious for three days; my family chose not to tell me, because I was far away and there was nothing I could do. I often lived with an aching emptiness inside me. I learned early on that living a world away meant I would have to work harder to stay close to the people I loved.

• • •

M

EXICO

C

ITY

was about to empty out for a holiday weekend. El Distrito Federal, or el D.F., as Mexicans called the capital city, was a sprawling mass of concrete blocks, intricately designed bronze statues, and colonial-era buildings, some bereft of character, others lovely Latin American haciendas. A thick haze of pollution formed a perpetual milky umbrella over the city; cars, especially lime-green Volkswagen Bug taxis, choked the wide avenues. The DF’s sprawl and chaos was intimidating, uninviting.

Marion already had a new boyfriend, a professional mountain biker who led tours through the countryside for semiprofessional mountain bikers. On Easter weekend, they were going to the nearby state of Veracruz, and I suggested that Marion and I go along with them. I was a tomboy growing up and didn’t think it could be that hard to ride a bike. From the town of Papantla de Olarte, a dozen of us set off through countryside lush with the yellow flowers of vanilla plants. The first time I hit the front brakes at top speed, I flew over the handlebars.

I decided to spend the rest of my weekend riding in the support van. A young Mexican man with a thick mess of brown hair named Uxval was one of the guides. He spoke Spanish, English, Italian, and just enough of every other language to be able to charm women around the world. He was engaged to be married, but there was an uncomfortable chemistry between us immediately. Like most mama’s boys, he was strategically in touch with his feminine side. Everything about his personality was deliberate. When we said good-bye, I wished him well with his marriage.

Two days later he called and asked if he could come by the apartment I shared with two American roommates. I gave him my address, and he arrived within a few hours. He walked in the door and pulled me close and kissed me. We stood there embracing for what seemed like hours, and when we stopped, he turned around to leave.

“I just had to do that before I did anything else,” he said and walked out the door.

Uxval broke off his engagement with his fiancée that night. I was apprehensive about getting involved with someone who would break an engagement over a gut attraction to a relative stranger, but I was attracted to his decisiveness. A few years earlier my grandmother Nina sat me down at her kitchen table in Hamden, Connecticut, to talk about love. I had just broken up with Miguel, who was reserved and passive, and I was at that tender age when decisions about love and life seemed somehow intertwined, when the questions of whom to love and what profession to choose seemed essentially the same question: How do you want to live? “I’ll tell you a secret,” she said coyly, as if she were going to tell me that she and my grandfather French-kissed before they were married. What she told me would stay with me for life.

“I used to go with this fellow, Sal,” she said. “Years ago Sal would pick me up from work and walk me home to my doorstep. We used to sit on the concrete steps for hours on Sherman Avenue. We would walk from Sherman to Chapel Street to pass the time and see the shows, the Paramount, you know. He was funny and spontaneous, and back then there was nothing to do but walk and go to the theater for twenty-five cents. He made me laugh, and he would grab me and kiss me all the time. But he didn’t have a pot to piss in. He had no money. He was a hard worker. He worked long, long hours and helped his mother out taking care of his brothers and sisters. But he never had any money. No future.

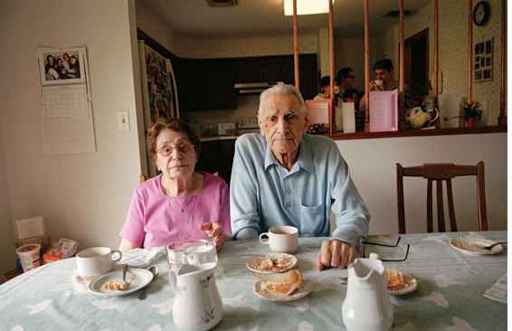

Nina and Poppy having coffee at home, May 2005.

“We went our separate ways, and soon enough my friend Eleanor fell for him. She was crazy for him, and he liked her, too. He treated her real nice, and she was mad about him. She cooked for him all the time and tended to his every need. He was a hard worker. He always made sure that she was all right. I was already with Ernie.

“Don’t get me wrong, your grandfather was a good provider. He was a good provider, and he trusted me with everything. I never had to show him the receipts from the grocery store. My sisters still do this with their husbands. Your grandfather gave me my freedom. He let me play cards on Quinnipiac Avenue and never told me I had to be back at a certain time. When his brothers came over, Ernie would sit at the table and watch us play. He didn’t like to play, but he would sit and watch and talk with us.

“Eleanor and Sal were doing well. They stayed married right up until the end. I have no regrets. Your grandfather can be a little distant, but he is a good man. I hear Eleanor has Alzheimer’s disease, and it gets progressively worse. I say, ‘You know, Ernie, I think I will call Sal to tell him I am sorry about his wife—invite him by for coffee.’ ‘Sure,’ Ernie says, not listening. So one day when your grandfather is at work, the doorbell rings. It is Sal. Eleanor is by now in a home, and he comes in. We talk, reminiscing of when we were sixteen years old, walking down the main boulevard in Hamden. I tell him I’m sorry about his wife, and we finish our coffee. He’s on the way to the hospital. I walk him to the front door, and in the foyer before we reach the door Sal grabs me. He grabs me and kisses me like I haven’t been kissed since those golden days when he would walk me home from work down the main boulevard. ‘I have been waiting over fifty years to do that, Antoinette,’ he says. ‘I know,’ I said, and I walked him out.