J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets (40 page)

Read J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets Online

Authors: Curt Gentry

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #United States, #Political Science, #Law Enforcement, #History, #Fiction, #Historical, #20th Century, #American Government

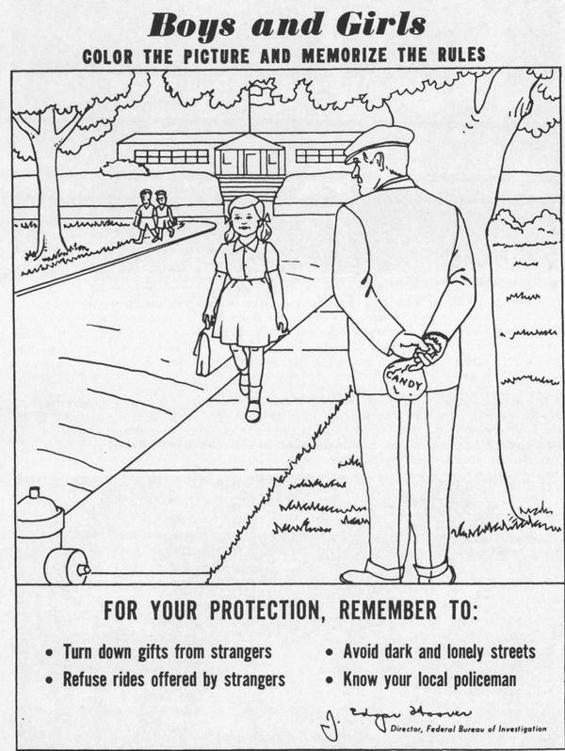

Hoover believed that the morality of America was his business. In addition to ghost-written articles warning the public about the dangers of motels and drive-in “passion pits,” the FBI distributed the above child molester’s coloring leaflet. “We had not anticipated at the time it would be so favorably received,” Hoover told Congress, “but it was immediately taken up by hundreds of law-enforcement agencies, newspapers, and civic groups throughout the country to promote child safety through coloring contests.”

Finally tiring of his “fun with the FBI,” Bridges invited some reporters up to watch the show. He also let them examine the microphone he’d removed from his telephone box, as well as the notarized statement of a young woman the agents had invited up to listen to the tap.

*

Looking across the street and suddenly realizing from the smiling faces that

they

were under surveillance, the two agents fled the room so hastily they left behind a report with an FBI letterhead.

21

On learning of the incident, Clyde Tolson severely censored both agents;

†

Lou Nichols tried, unsuccessfully, to have the story killed

(P.M.

ran it on its front page, while McKelway’s piece, which became a much anthologized classic, appeared in the

New Yorker

several months later in 1941—earning both the newspaper and the magazine a place on the Bureau’s “not to be contacted” list); and a mortified J. Edgar Hoover was forced to confess the embarrassing incident to the attorney general.

“I could not resist suggesting to Hoover that he tell the story of the unfortunate tap directly to the President,” Biddle recalled. “We went over to the White House together. FDR was delighted; and with one of his great grins, intent on every word, slapped Hoover on the back when he finished. ‘By God, Edgar, that’s the first time you’ve been caught with your pants down!’ ”

22

Hoover obviously did not think it that funny. When Biddle included the story in his autobiography,

In Brief Authority,

which was published in 1967, Hoover called the former attorney general a liar and denied the White House incident had ever taken place. By then, of course, Roosevelt was long dead and no longer able to contradict him.

Aware that “the two men liked and understood each other,” Attorney General Biddle never complained when Roosevelt and Hoover met privately, without him. Nor did he see such meetings as circumventing his authority. Rather, knowing that “the President cared little for administrative niceties,” he presumed that it was always Roosevelt, and never Hoover, who had requested the meetings. He believed this because Hoover had told him it was so. “Not infrequently [Roosevelt] would call Edgar Hoover about something he wanted done

quietly, usually in a hurry; and Hoover would promptly report it to me, knowing the President’s habit of sometimes saying afterward, ‘By the way, Francis, not wishing to disturb you, I called Edgar Hoover the other day about…’ ”

23

Francis Biddle was the first attorney general who made a serious attempt to study J. Edgar Hoover. He was neither the first, nor the last, attorney general J. Edgar Hoover “analyzed”—and, as usual, all too accurately.

With direct access to the president, an attorney general who went along with almost everything he requested, and the FBI’s authority recently expanded to include not only domestic intelligence but all foreign intelligence in the Western Hemisphere,

*

Hoover should have been content. But he wasn’t. He wanted more, much more.

In his June 3, 1940, diary entry, Adolf Berle wrote, “…to J. Edgar Hoover’s office for a long meeting on coordinated intelligence. We agreed that we would set up a staff that I have been urging, plans to be drawn here…We likewise decided that the time had come when we would have to consider setting up a secret intelligence service—which I suppose every great foreign office in the world has, but we have never touched.”

24

In his conversations with Roosevelt, Berle, and particularly his own aides, it was obvious that Hoover was aiming at a specific goal, which was nothing less than expanding the Federal Bureau of Investigation into a worldwide intelligence-gathering organization.

Unfortunately for Hoover, others had similar ideas. And because of their secret planning, Hoover would lose that much coveted prize, to none other than William “Wild Bill” Donovan.

With the outbreak of the war in Europe, the FBI had cut its liaison with British intelligence, in compliance with a mandate from the State Department which maintained that any form of collaboration would infringe on U.S. neutrality.

With tons of badly needed shipping threatened by the activities of German agents in the Western Hemisphere, the British, and in particular Winston Churchill, were especially anxious to reestablish a close working relation with U.S. intelligence, and for this purpose in the spring of 1940 William Stephenson

(code name Intrepid) was sent to the United States to approach the FBI director.

A mutual friend, the boxing champion Gene Tunney, provided the introductions. Hoover listened attentively as Stephenson presented the British proposal. The argument was made even more convincing by Stephenson’s disclosure that a code clerk in the American embassy in London—the domain of Ambassador Joseph Kennedy—had been intercepting communications between Roosevelt and Churchill and turning them over to the Germans.

Hoover responded by saying that although he would welcome working with the British, he was prohibited from doing so by the State Department mandate: “I cannot contravene this policy without direct presidential sanction.”

“And if I get it?” Stephenson asked.

“Then we’ll do business directly,” Hoover replied. “Just myself and you. Nobody else gets in the act. Not State, not anyone.”

“You will be getting presidential sanction,” Stephenson told him.

Another mutual friend, Ernest Cuneo, was chosen to approach Roosevelt. According to Cuneo, the president responded enthusiastically, telling him, “There should be the closest possible marriage between the FBI and British intelligence.”

25

If Roosevelt put his approval in writing, the document has never surfaced. More likely, his permission was oral.

*

Even at that, it was a politically dangerous act: given the isolationist sentiment at the time, had the agreement been made public, it could conceivably have resulted in an impeachment attempt and would almost certainly have been used against Roosevelt in his 1940 reelection bid.

Operating under the guise of a British trade commission, Stephenson set up the British Security Coordination (BSC), their cooperation at this early stage being so close that Hoover himself suggested the name. Although its headquarters was a small suite—Room 3606—in Rockefeller Plaza in New York, at its peak about one thousand persons worked for the BSC in the United States and about twice that number in Canada and Latin America. Its largest single operation was in what seemed a most unlikely location, Bermuda. However, all mail between South America and Europe was routed through there, including diplomatic pouches, and the BSC set up a mammoth, highly sophisticated letter-opening center, complete with code breakers, the fruits of which it shared with the FBI.

It was an odd marriage—the British quickly realized that Hoover was an Anglophobe

†

—but for a time it worked. During 1941 alone, the BSC provided

the FBI with over 100,000 confidential reports. Better yet, from the FBI point of view, Stephenson, who didn’t want any publicity regarding his activities, was quite content to let Hoover claim full credit for British successes.

It is possible to pinpoint exactly when the marriage went sour: it occurred on July 11, 1941, when Roosevelt appointed William Donovan head of the Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI).

Though classmates at Columbia Law School, Donovan and Roosevelt had been neither social equals nor friends. In 1932, during his unsuccessful bid for the governorship of New York, Donovan had even campaigned against FDR. However, as the situation in Europe worsened, John Lord O’Brian convinced the president that his much traveled protégé would be a good choice for any “special assignments” he might have, and Roosevelt, intrigued by the idea, sent Donovan on a number of secret missions, including several to Great Britain, where—circumventing the defeatist Joseph Kennedy—he dealt directly with Winston Churchill and other high British officials.

Aware that Donovan provided direct access to the American president, William Stephenson quickly “co-opted” him. Donovan was given an inside view of British intelligence, with special emphasis on code breaking, sabotage, counterespionage, and psychological and political warfare. Stephenson also convinced Donovan that the United States was badly in need of its own coordinated, worldwide intelligence agency. Donovan, armed with accurate and impressive military intelligence provided by the British, in turn convinced Roosevelt; and in July 1941—much to the displeasure of Hoover and his rivals in the State Department, Army, and Navy—the president appointed Donovan chief of a new organization called the Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI), a year later renamed the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

Although he did everything in his power to oppose Donovan’s appointment, Hoover was partly responsible for it. For months the FBI director had been battling with General Sherman Miles, head of Army intelligence, over

which

of their organizations had

what

intelligence authority. The president, Richard Dunlop has noted, “exasperated by the intransigence and narrow-minded bickering of Miles and Hoover, decided that an integrated strategic intelligence service was long overdue,” and adopted the Donovan-Stephenson plan.

28

“You can imagine how relieved I am after months of battle and jockeying in Washington that our man is in position,” Stephenson cabled London.

29

Well aware of Stephenson’s efforts on Donovan’s behalf, Hoover stopped cooperating with the BSC. He continued to use its reports, sending them on to Roosevelt as if they were his own, but, as the British soon discovered, it was now a one-way street.

“The FBI in its day-to-day working relations were always superbly helpful,” the BSC’s Herbert Rowland recalled. “Hoover only began ordering his department heads to cut us off after he saw Roosevelt had bought Stephenson’s arguments for an integrated and co-ordinated intelligence service.”

30

Lieutenant Commander Ewen Montague, the “dirty tricks” expert on Stephenson’s

staff, saw it coming. Hoover, Montague recalled, “wanted to publicize everything to enhance the FBI’s reputation. We dared not confide to him certain plans for fear of leaks. Our methods depended on concealment. This made Hoover most distrustful. A ghastly period began.”

31

Even at that, the BSC fared better than Donovan’s new organization. On orders from Hoover, specially selected FBI agents infiltrated the fledgling COI, some later rising to key positions in both the OSS and its successor, the CIA. Since the FBI was charged with conducting background investigations of all COI/OSS applicants, Hoover knew the identities of Donovan’s agents, many of whom were kept under surveillance. One of Hoover’s closest allies in Washington, Mrs. Ruth Shipley, who ran the U.S. Passport Office as her own fiefdom, had the passports of Donovan’s supposedly secret operatives stamped “OSS,” until a complaint to the president stopped the practice. Hoover, who had first opened a file on Donovan back in 1924, when he was his nominal superior in the Justice Department, now added to it reports on his security lapses,

*

financial dealings, and numerous extramarital involvements. Whenever Donovan or his men made a serious mistake—and former COI/OSS officers admit there were many such—Hoover fired off a memorandum to the White House. For example, acting on their own, OSS agents broke into the Japanese embassy in Lisbon, Portugal, and stole a diplomatic codebook—unaware that U.S. intelligence had already broken the code. With the discovery of the loss, the ciphers were changed and Donovan added to his growing list of bureaucratic enemies the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Even relatives of OSS officials did not escape Hoover’s attention. In 1942 a Polish college professor applied for a job with the FBI as a Russian translator. FBI surveillance revealed that he was carrying on an affair with Eleanor Dulles, sister of Allen and John Foster, the pair having met secretly three times a week (every Tuesday, Saturday, and Sunday) for five years, and Hoover rejected him for this reason. Donovan, to whom Hoover’s enmity was the highest recommendation, quickly hired him, remarking, “We need Russian analysts more than Hoover does.”

†

33

All too often Donovan made himself an easy target. His hiring practices, for example, were sloppy at best. Ernest Cuneo recalled that once Donovan requested a special entry visa for a man he’d hired, but that Hoover had blocked it. The problem, Donovan told Cuneo, was that the man had committed “a few youthful mistakes.” Cuneo approached Attorney General Biddle, who said he

was sure the youthful escapades could be overlooked. Cuneo had scarcely returned to his office when the telephone rang and Biddle ordered him to get right back to the Department of Justice. The FBI director was with the attorney general when he arrived. “

A few youthful mistakes?

” Biddle uncharacteristically shouted. “

Tell him, Edgar!

” Hoover read the man’s rap sheet, which included two convictions for homicide in the first degree, two manslaughters, and a long list of dismissed indictments.

35

Hoover made sure such incidents received wide circulation in the intelligence community.