Jack Pierce - The Man Behind the Monsters (9 page)

Read Jack Pierce - The Man Behind the Monsters Online

Authors: Scott Essman

In Lon Chaney, Jr., opposite bottom left, the Universal Studios of the early 1940s had their new Karloff—a versatile actor who could enliven their many monster franchises. From 1941 to 1944, Chaney Jr. would appear in sequels to

Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy

, and

The Wolf Man

, in addition to making several original films. Jack Pierce’s first collaboration with Chaney Jr. was

Man-Made Monster

(1941), opposite top, in which they presented a man invulnerable to electricity. Then, following the success of

The Wolf Man

later that year, Chaney Jr. was cast in three Mummy sequels playing the doomed Egyptian prince Kharis (opposite bottom right):

The Mummy’s Tomb

(1942),

The Mummy’s Ghost

(1944) and

The Mummy’s Curse

(1944). All featured the actor in a heavily modified version of the original

Mummy

makeup that Pierce had fashioned for Karloff. Where Pierce’s makeup for Tom Tyler in

The Mummy’s Hand

retained Tyler’s basic facial features, Chaney was fairly unrecognizable in his Mummy incarnations. In fact, despite his objection to using appliances, Pierce undoubtedly created full facial masks for several of Chaney Jr.’s Mummy appearances, plus additional “double” masks for Eddie Parker, who was Chaney Jr.’s regular standin/double/stuntman. Pierce also worked with Chaney Jr. on both

Ghost of Frankenstein

(1942) as the Monster and

Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man

(1943), above, as Larry Talbot/The Wolf Man. In 1944, Pierce and Chaney created the character for

Dead Man’s Eyes,

left, taking the concept of Chaney Jr.’s blind character receiving an eye transplant to a grisly conclusion.

In 1943, Universal cast Chaney, Jr. as the lead character in the atmospheric horror thriller

Son of Dracula

(above), oddly, a dozen years after the first

Dracula

and a full seven years after

Dracula’s Daughter

—an atypical practice for the release of sequels in that time period. Though

Son of Dracula

did not offer Pierce the challenge of creating a completely original monster character in the same stead as his other horror creations, it allowed him the chance to use his considerable hair work skills.

It is no secret that Chaney Jr. and Pierce had their disagreements. The actor, whose father Pierce had idolized and called both friend and mentor, was intolerant of the long hours and crude methodology that Pierce undertook in realizing the monster characters. If the makeup for

The Wolf Man

was uncomfortable—supposedly hot, itchy and malodorous—Chaney Jr. was no more pleased with his Mummy makeup and costume (right). Pierce, in all his attention to detail, insisted on applying the necessary “muck,” as Chaney called it, on a daily basis while the actor waited, as patiently as he could. He once signed a photo to Pierce as follows: “

To the greatest goddamned sadist in the world.

”

- L.C.

films with abbott & costello

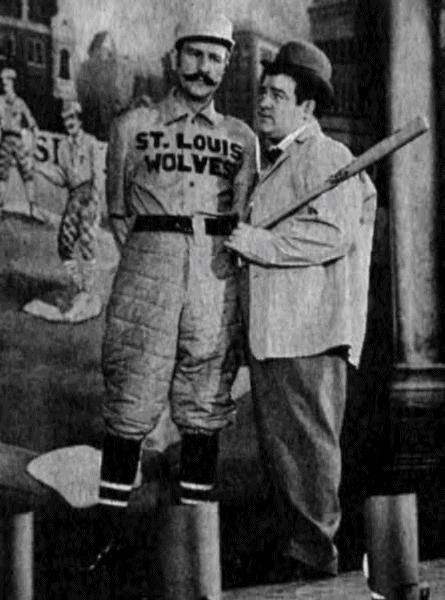

Among Jack Pierce’s fondest assignments as head of

Universal’s makeup department in the 1940s were those

with comedy duo Abbott and Costello. As the top box

office draw at the studio, Abbott and Costello worked

more than any other Universal team or franchise, mak

ing some 16 films by the time Jack Pierce left the studio.

Pierce was chiefly brought in for specialized assignments,

and Abbott and Costello most likely worked more closely

with Pierce’s assistants like Abe Haberman in that period.

Strangely, though Jack Pierce had been head of

Universal’s makeup department since 1928, he didn’t

receive a screen credit on any Abbott and Costello film

until

The Naughty Nineties

in 1945 (top right), which

featured the legendary “Who’s on First?” routine.

Nonetheless, the Abbott and Costello experiences were important to Pierce on a personal as well as professional level. Producerdirector Arthur Lubin and Pierce became fast friends in the early 1940s—Lubin directed the first five successful Abbott and Costello films at the studio (pictured above right on the set of

In the Navy

), in addition to Pierce makeup vehicles such as

The Phantom of the Opera

with Claude Rains. He and Pierce remained friends through the 1940s even as Lubin left the studio, when he issued Pierce this friendly letter in November, 1945:

“Dear Jack, As you have undoubtedly heard, I have left Universal after an association of many years. I can’t say goodbye without first expressing my sincere appreciation for your friendship and kindness. I feel that, without your help, whatever measure of success I may have achieved in my work here would not have been possible. If in any way in the future, I can be of service, I shall. I want you to feel that I take with me a very warm regard for you wherever I may go. Cordially, Arthur Lubin.” Pierce could not have known then how prophetic those words would be in years to come. Other important associations with Abbott and Costello filmmakers included one with Charles Barton, who directed eight films with the duo after Lubin left Universal. In fact, Pierce was working on the sequel to Abbott and Costello’s first feature film success

Buck Privates

in the spring of 1947 when a “horror-comedy” that had long been planned was announced. However, on the set of that film — Barton’s

Buck Privates Come Home

— Pierce and other Universal mainstays, including Vera West and John P. Fulton, were fired from the studio that they had called home for nearly 20 years. The announcement, by new studio chief William Goetz, must have been especially shocking to Jack Pierce, who, in his 30 years of loyalty to Universal Studios, never once signed a contract with studio bosses.

pierce in the 1950s

In 1947, having been let go by Universal Studios, Jack Pierce faced the second half of his career at the age of 58. His fortunes were furthered tainted by the reality that studios of the era had lost interest in making horror films. With the real horrors of World War II in the past, only lighter fare such as 1948’s Universal romp

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein

was put into production. Moreover, that film, which was being planned by director Charles Barton when Pierce was dismissed from his duties at Universal, utilized Pierce designs for the Frankenstein Monster, the Wolf Man and Dracula, but new makeup supervisor Bud Westmore and his team realized those characters with more sophisticated makeup techniques than Pierce had in his arsenal. Jack Pierce once proudly claimed that he did not use appliances (though it is fact that he used at least partial appliances on

The Wolf Man

and the

Mummy

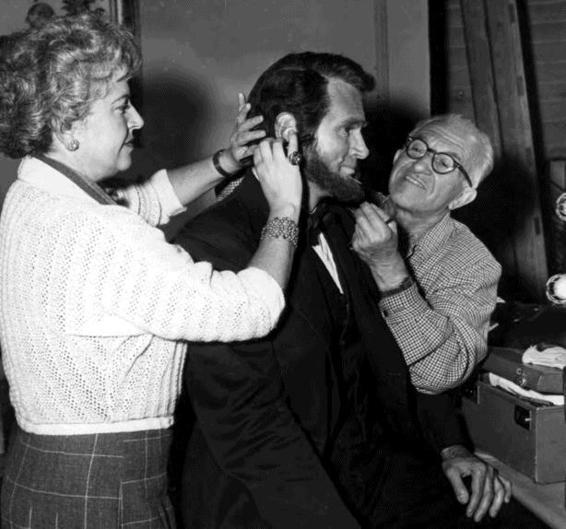

sequels), but in the late 1940s and early 1950s that statement did not serve him well. Pierce’s methods were seen as archaic in the era of George Bau’s foam latex formula and techniques. And despite Pierce’s indisputable talents, his age and high standards were likely seen as a hindrance rather than an advantage. Thus, Jack Pierce, creator of the classic monsters of cinema, was relegated to work as a freelancer on often substandard material, rarely making use of his specialized skills. Occasionally, Pierce’s projects in this time allowed him to stretch his creative wings, including an episode of the popular 1950s show

You Are There

in 1955 in which he and former Universal co-worker Carmen Dirigo transformed Jeff Morrow into Abraham Lincoln (above).