Jefferson and Hamilton (70 page)

Read Jefferson and Hamilton Online

Authors: John Ferling

Jefferson saw Hamilton as a counterrevolutionary, which was neither entirely correct nor totally incorrect. More than any other figure in the early years of Washington’s presidency, Jefferson mobilized the resistance and provided the ideology against the darker things for which Hamilton stood. With his unsurpassed grasp of political reality, Jefferson was instrumental in stopping Hamiltonianism. No one knows what the United States might have become by the fiftieth anniversary of independence had Hamilton and the High Federalists had their way. What we do know is that the sweeping democracy and propulsive egalitarianism of 1826 America owed more to Jefferson than to any other Founder.

While Hamilton’s focus was on a strong and independent United States, Jefferson dreamed of making the world a better place. He divined that what

he called the “corrupt squadrons of stockjobbers” were the inevitable handmaidens of Hamiltonianism, and he understood that once such forces were unleashed, it would be doubtful at best that those who governed would act to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number. Empathetic toward those who faced the miseries wrought by manufacturing, ambitious entrepreneurs, and capricious market forces, Jefferson also feared that, in time, the world Hamilton sought would consist of a prosperous few who lived sumptuously while the great majority remained propertyless and mired in squalor. Jefferson’s agrarian idyll, the polar opposite of Hamiltoniansim, envisaged a promised land of virtuous, republican, property-owing farmers who had little need of a powerful centralized government, who would never yearn for the rule of “angels, in the form of kings,” and who would be independent of the long and awesome clout of the social and economic elite. Such a society, overseen by republican governance, was the “world’s best hope,” he said in his inaugural address.

42

It was a dream, and dreams do not always come true, but for most members of the several generations following Jefferson’s death, America more closely resembled Jefferson’s dream than it did the reveries of Hamilton.

Today’s America is more Hamilton’s America. Jefferson may never have fully understood Hamilton’s funding and banking systems, but better than most he gleaned the potential dangers that awaited future generations living in the nation state that Hamilton wished to bring into being. Presciently, and with foreboding, Jefferson saw that Hamiltonianism would concentrate power in the hands of the business leaders and financiers that it primarily served, leading inevitably to an American plutocracy every bit as dominant as monarchs and titled aristocrats had once been. Jefferson’s fears were not misplaced. In modern America, concentrated wealth controls politics and government, leading even the extremely conservative Senator John McCain to remark that “both parties conspire to stay in office by selling the country to the highest bidder.”

43

The American nation, with its incredibly powerful chief executive, gargantuan military, repeated intervention in the affairs of foreign states, and political system in the thrall of great wealth, is the very world that Jefferson abhorred.

Hamilton and Jefferson had their champions and detractors in their lifetimes, and both have been lionized and criticized by politicians and scholars ever since. The exaltation of Hamilton began immediately after his shocking demise. Two days later, as bells pealed throughout Manhattan, Hamilton’s body was conveyed to Trinity Church along city streets lined with the grieving and the curious. Mourners streamed in for two hours to pay their respects, after which the doors to the church were closed for a formal service

attended by those with whom Hamilton had most closely associated. His family was present, of course, and so too were officers from the Continental army and the New Army, and several Manhattan lawyers, merchants, and bankers. Columbia’s faculty and students were also admitted. The ubiquitous Gouverneur Morris delivered an extended, sorrowful eulogy. Morris ignored Hamilton’s years in the West Indies and omitted mentioning what he had recently confided to his own diary: Hamilton not only was “indiscreet, vain and opinionated,” but he was also “on Principle opposed to republican and attached to monarchical Government.” Morris hit his stride when he spoke of Washington taking Hamilton as an aide: “It seemed as if God had called him suddenly into existence that he might assist to save a world!” The “single error” of Hamilton’s life had been his belief that the Constitutional Convention had not created a sufficiently powerful national government. Calling Hamilton the most “splendid” member of Washington’s cabinet, Morris attributed the nation’s “rapid advance in power and prosperity” to Hamilton’s economic policies. Morris admonished the audience, when faced with difficult choices, to ask: “

Would Hamilton have done this thing

?” He closed with an appeal: “I CHARGE YOU TO PROTECT HIS FAME—It is all he has left.”

44

In Charlottesville, Virginia, bells rang when Jefferson died. The students at the university, and many residents of the village, donned black crepe armbands. All businesses in town remained closed on July 5, the day of the funeral. Though it rained, the service was held outdoors at the family burial plot at Monticello. Students and faculty from the university, many neighbors and residents of Charlottesville, and some who had been Jefferson’s slaves attended. All stood in the wet, emerald green grass listening to the rector of the local Episcopal church. When he was done, the coffin was lowered into a freshly dug grave next to that of Jefferson’s wife. A month or so later, a six-foot obelisk headstone was placed atop a three-foot-square slab that rested on the grave.

45

The gravestone bore an inscription composed by Jefferson:

HERE WAS BURIED THOMAS JEFFERSON

AUTHOR OF THE DECLARATION OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE

OF THE STATUTE OF VIRGINIA FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM

& FATHER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA.

His coffin had been made by John Hemings, the fifty-year-old half-brother of Sally.

No one knows where Sally Hemings is buried.

The Wren Building, one of the three buildings at the College of William and Mary when Jefferson attended the institution beginning in 1760. (Photograph by Jrcla2 via Wikimedia Commons.)

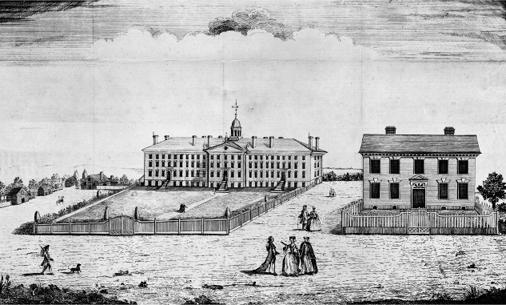

Nassau Hall at King’s College (later Columbia University), where Hamilton enrolled in 1773 or 1774. (Encyclopedia Britannica/UIG/The Bridgeman Art Library.)

Jefferson’s drawing of the original Monticello. He began construction in 1768, but demolished the dwelling in 1794 and began work on the mansion that is familiar today. (Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston/The Bridgeman Art Library.)

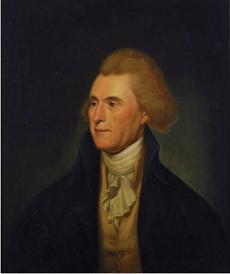

Thomas Jefferson in 1776 at age thirty-three. Charles Willson Peale was the artist. (The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens/The Bridgeman Art Library.)

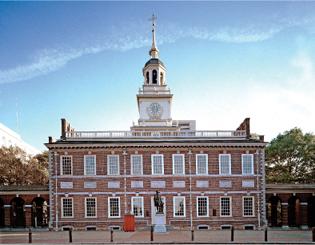

The Pennsylvania State House, now known as Independence Hall. Congress met here while Jefferson was a member from 1775–76 and during most of Hamilton’s brief stint in Congress from 1782–83. It was home to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.)

Alexander Hamilton (1757–1804) in the Uniform of the New York Artillery

, a mid-nineteenth-century painting by Alonzo Chappel. A Continental soldier who observed Hamilton during the 1776 retreat across New Jersey described him as “a youth, a mere stripling, small, slender, almost delicate in frame, marching … with a cocked hat pulled down over his eyes, apparently lost in thought, with his hand resting on a cannon, and every now and then patting it as [if] it were a favorite horse or a pet plaything.” (The Bridgeman Art Library.)