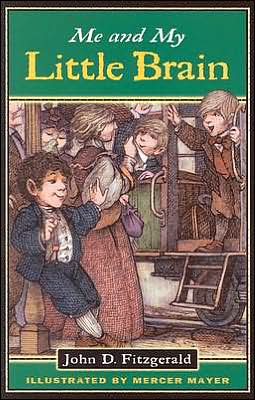

John Fitzgerald

Authors: Me,My Little Brain

Me and My Little Brain

By John D. Fitzgerald

Contents

The

Wheeler-Dealer

A Born

Loser

Frankie

Pennyworth

Cutting

Frankie's Mental Block

Frankie

Takes Over

The

Escape of Cal Roberts

Hostage

My

Little Brain Against Cal Roberts

CHAPTER ONE

The Wheeler-Dealer

ON THE SECOND MONDAY of September in 1897 I

was sitting on top of the world. Well, to tell the truth, I wasn't actually

sitting on top of the world. I just felt as if I were. I was sitting on the top

rail of our corral fence watching Frank Jensen doing all my chores. It reminded

me of

the

hundreds of times my brother Tom had sat on

the corral fence watching me do all his chores. He had bamboozled me into doing

his share of the work so many times that Mamma and Aunt Bertha were both

astonished whenever they saw him carrying in a bucketful of coal or an armful

of kindling wood. And that is why I felt as if I were sitting on top of the

world.

I had been the victim of Tom's great brain

more times than a horse switches its tail knocking off flies in the summertime.

He had swindled me out of my birthday and Christmas presents until there was no

sense in me having a birthday or receiving Christmas presents. I wasn't the

only kid in

Adenville

, Utah, who had been victimized

by my brother's great brain. Tom didn't play any favorites when it came to

being the youngest confidence man who ever lived. There wasn't a kid in town

who hadn't been swindled by my brother.

I didn't hold a grudge against Tom for the

many times he had put one over on me. I was actually grateful. When a fellow

has been the victim of every confidence trick in the book, he gets to be pretty

darn sharp himself. So sharp, I was positive I could step right into Tom's

shoes after he left for the Catholic Academy in Salt Lake City with my oldest

brother,

Sweyn

.

Adenville

had a

population of about two thousand Mormons and about five hundred Protestants and

Catholics. We had a one-room schoolhouse where Mr. Standish taught the first

through the sixth grades. Any parents who wanted their children to get a higher

education had to send them to Salt Lake City.

Sweyn

was starting his second year at the Academy. Tom was only eleven but going to

the Academy because he was so smart Mr. Standish had let him skip a grade. I

was only nine years old and wouldn't be going away to school for a few years.

I thought I would bawl like a baby when Tom

left. I felt sad about having a brother I loved leave home. I knew I would miss

him very much. But at the same time I couldn't help feeling sort of

relieved.

Mamma and Aunt Bertha carried on as if my

brothers were going off to war as the train left the depot.

"I feel so sorry for my two

boys," Mamma cried. "They are so very young to be leaving home."

Papa put his arm around Mamma's shoulders.

"If you must feel sorry for anybody," he said, "feel sorry for

the Jesuit priests at the Academy who are going to have to put up with the

Great Brain for the next nine months."

I know that sounds like a cruel thing for a

father to say. Papa was editor and publisher of the

Adenville

Weekly Advocate and was considered one of the smartest men in town. But Tom had

made a fool out of Papa almost as many times as he had me. Maybe that was why

Papa had said what he did. Sometimes I thought Tom had made Papa and me his

favorite victims because we looked so much alike. I was a real leaf off the

Fitzgerald family tree. I had the same dark curly hair and deep brown eyes that

Papa had. Anybody could tell I just had to be his son by looking at us.

Sweyn

was a blond and looked like our Danish mother. Tom

didn't look like Papa and he didn't look like Mamma unless you sort of put them

both together.

I couldn't help feeling a sense of great

power after Tom was gone from

Adenville

. I knew I

only had a little brain compared with Tom's great brain. But I believed I'd

learned enough from my brother to outsmart any kid in town. I knew I wasn't a

genius like Tom when it came to putting one over on Papa or Mamma and other

adults in town. But my brother had taught me that adults are pretty dumb, and a

kid who uses his head can fool them most of the time. The time had come for me to

take over where Tom had left off.

Tom and I had

each received ten cents a week allowance for doing our chores. I know that

doesn't sound like much, but back in the 1890's a dime would buy what it costs

fifty cents or more to buy today. Soda pop was only a penny and so was a

double-scoop ice cream cone. Papa increased my allowance to twenty cents a week

for doing all the chores after Tom left home. This was a windfall because Tom

had

connived

me into doing all the chores about ninety

percent of the time anyway. I could see no reason for me ever doing any more

chores now that I had an allowance of twenty cents a week.

I didn't get a chance to start wheeling and

dealing until the Saturday after school started. I rode Tom's bike over to

where Frank and Allan Jensen lived, on the outskirts of town. I knew the Jensen

family was very poor. Allan was fourteen but his parents couldn't afford to

send him away to school. Frank was twelve years old. They both had blond hair

that was almost white. It grew funny down over their foreheads so a shock of it

was always sticking out under the visors of their caps.

They were hauling manure from their barn to

spread on their big vegetable garden. Everybody put manure on their gardens in

the fall. Then in the spring they would spade or plow it under before planting.

It not only fertilized the ground but also kept all kinds of bugs out of the

gardens.

Frank and Allan were using a stone sled to

haul the manure. Practically everybody owned a stone sled in those days. They

were made with two-by-four runners sawed at an angle in front. More

two-by-fours or thick boards were used to build a platform. Holes were drilled

in the front part of the runners. A rope or chain was hooked through the holes

and to the tugs of a horse's harness. They were called stone sleds because they

were originally used by early pioneers to haul stones to build fireplaces. They

were very handy for small hauling jobs instead of using a wagon. Frank and

Allan were in their barn loading manure on their stone sled with pitchforks

when I walked in, wheeling Tom's bike.

"I have a

proposition to make you," I said.

They both stopped working and leaned on the

handles of their pitchforks.

Allan asked,

"What kind of a proposition?"

"I'll pay you five cents a week to do

my chores," I said. "You can take turns each week."

Allan looked steadily at me. "Just

what do you call chores?" he asked.

"Once a day you fill up all the

woodboxes

and coal buckets in the parlor, dining room,

bathroom, and kitchen," I said. "And you feed and water our team of

horses and the milk cow and

Sweyn's

mustang, Dusty.

And you milk the cow and feed and water the chickens."

Allan shook his head. "That is a lot

of work for just a nickel a week," he said.

I was expecting him to say just that. Tom

had taught me when making a deal to always offer only half at first. Then when

you double it, a kid will think he is getting a good deal.

"I'll make it a dime a week," I

said. "That will give each of you a nickel a week spending money."

Allan looked at his brother and then back

at me. "No mowing the lawn or weeding the garden or chopping kindling wood

or things like that?" he asked.

"No," I said. "If the lawn

needs cutting or there are weeds to pull, I'll do it. And my father always

chops our kindling wood for exercise."

Allan nodded. "We'll take it," he

said. "When do we start?"

"Monday after school," I

answered.

"When do we

get paid?" Allan asked.

"I'll pay you every Monday for the

previous week's work," I said.

We all shook hands to seal the bargain. I'd

pulled off my first big deal. Frank and Allan would be doing all my chores for

ten cents a week. That left me a neat profit of a dime a week for doing

nothing. Now all I had to do was think up a good story to tell Papa and Mamma.

I couldn't help

feeling very proud of myself as I rode Tom's bike down Main Street on my way

home. I had

Adenville

in the palm of my hand. It

wouldn't surprise me if I ended up becoming the youngest mayor in Utah. As its

mayor,

Adenville

was a town of which I could be

proud. It was a typical Utah town, depending upon agriculture since the closing

of the mines in the nearby ghost town of

Silverlode

.

We had electric lights and telephones. The streets were wide and covered with

gravel. There were wooden sidewalks in front of the stores. We had sidewalks

made from ashes and cinders in front of homes. All the streets were lined with

trees planted by early Mormon pioneers. The railroad tracks separated the west side

of town from the east side. All the homes and most of the places of business

were on the west side. There were just a couple of saloons, the

Sheepmen's

Hotel, Palace Cafe, the livery stable, the

blacksmith shop, and a couple of other stores and a rooming house on the east

side. When I rode down an alley and into our backyard, my dog Brownie and his

pup Prince came running to meet me. I put the bike on the back porch after

patting them on the heads. Brownie was a thoroughbred Alaskan malamute. The pup

was the pick of the litter after I'd mated Brownie with a sheep dog named Lady

owned by Frank and Allan Jensen. I walked to our barn and climbed up the rope

ladder to the loft. Papa and Mr. Jamison, the carpenter, had built the loft for

me and my brothers. They had laid boards across three beam rafters and nailed

them down. They had also made a wooden ladder up the side of the barn to the

loft. Tom, in his usual style, had taken possession of the loft. He had removed

the wooden ladder and replaced it with a rope ladder. This way he could climb

into the loft and pull the rope ladder up after him so nobody else could come

up. Tom had an accumulation of stuff in the loft ranging from an old trunk of

Mamma's to the skull of an Indian that Uncle Mark had given him. My Uncle Mark

was the Marshal of

Adenville

and a Deputy Sheriff.

Adenville

was the county seat and my uncle was Acting

Sheriff most of the time. Sheriff Baker spent a great deal of time tracking

down Paiute Indians who left the reservation in the county, and renegade Navaho

Indians who made raids into Southwestern Utah from Arizona. People said that

Sheriff Baker took care of the Indians and Uncle Mark took care of white

lawbreakers.

I sat down on one of the boxes in the loft.

I put my right hand under my chin and my elbow on my right knee just like a

picture I'd seen of a statue called "The Thinker." I figured this

position would help me think up a good story to tell Papa and Mamma. But I

found out the sculptor who had made the statue didn't know beans about

thinking. I couldn't think because the position was so darn uncomfortable. I

lay down on my back and stared up at the roof instead. I knew if I told Papa

and Mamma I'd hired Frank and Allan to do my chores for ten cents a week what

they would say. They would say if I was going to hire somebody to do my chores

I should pay them the whole twenty cents a week.

When I went to

bed that night I still hadn't thought up a good story. Then I remembered

something Tom had told me one time. He had said that a person's subconscious

mind was a hundred times smarter than his conscious mind. And he'd told me that

if a person just thinks about a problem before going to sleep, the subconscious

mind would solve the problem while the person was asleep. And when you woke up

in the morning the answer would be in your conscious mind. It sounded

complicated to me. But I was really concentrating on what I'd tell Papa and

Mamma when I fell asleep that night.