John Quincy Adams (29 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

Less than a month after their arrival, John Quincy and Louisa had to leave Quincy for their new home in Washington. They enrolled Charles Francis and his older brother John II in the prestigious Boston Latin School and took George Washington Adams to Cambridge to enroll in Harvard, but the faculty found the boy academically unprepared for admission. John Quincy arranged for him to board with the family of a Harvard faculty member who agreed to tutor the young Adams and prepare him for the college curriculum.

Satisfied that he had provided for the education of his sons, John Quincy set off with Louisa for New London, Connecticut, where they stepped aboard a steamboat for the first time in their lives. They “steamed” successively to New Haven, New York, and Philadelphia, covering in a day and a half, in comfortable quarters, a distance that would have taken three times longer by coachâand that produced a collection of bruises. They arrived in Washington on September 20, 1817, and went to stay with another of

Louisa's sisters and her husband until they could find their own property. In accordance with the President's instructions, John Quincy went immediately to confer with Monroe. Because of the thick, gleaming coats of white paint workers had slathered on its blackened exterior after the War of 1812, the presidential mansion had acquired a new name: the White House.

Louisa's sisters and her husband until they could find their own property. In accordance with the President's instructions, John Quincy went immediately to confer with Monroe. Because of the thick, gleaming coats of white paint workers had slathered on its blackened exterior after the War of 1812, the presidential mansion had acquired a new name: the White House.

Work on the interior was still progressing when John Quincy arrived to see the President. Out of deference for the secretary of state's first rank in the cabinet, Monroe had awaited John Quincy's arrival to announce his other cabinet appointees. The President had intended to ensure representation of all the nation's regions in his cabinet by naming Kentucky's Henry Clay as secretary of war, Georgia's William H. Crawford as secretary of the Treasury, Maryland's William Wirt as attorney general, and Benjamin Crowninshield of Massachusetts as secretary of the navy. Clay, however, lusted for the presidencyâand had sought appointment to head the State Department as his own “stepladder” to the White House. When Monroe appointed John Quincy, Clay decided to remain in his powerful, high-profile post as Speaker of the House rather than recede into semi-obscurity as a peacetime secretary of war. The President named John C. Calhoun of South Carolina instead.

Although John Quincy had expected cabinet members to work as a team, he realized after its first meeting that far from a cooperative venture, James Monroe's cabinet was a hornet's nest of ruthless, politically ambitious adversaries, bent on crushing his chances of becoming President. And beyond the confines of the cabinet meeting room, Henry Clay sat in Congress ready for every opportunity to promote his own candidacy by undermining John Quincy.

My office of secretary of state makes it the interest of all the partisans of the candidates for the next presidency . . . to decry me as much as possible in the public opinion.

The most conspicuous of these candidates are Crawford . . . Clay . . . and De Witt Clinton, governor of New York. Clay expected himself to have been secretary of state, and he and all his creatures were disappointed

by my appointment. He is therefore coming out as the head of a new opposition in Congress to Mr. Monroe's administration, and he makes no scruples of giving the tone to all his party of running me down.

29

by my appointment. He is therefore coming out as the head of a new opposition in Congress to Mr. Monroe's administration, and he makes no scruples of giving the tone to all his party of running me down.

29

Indeed, Clay, as Speaker of the House, acted immediately to restrict John Quincy's activities in the State Department with so low a budget that he could barely function. His salary, for example, was a mere $3,500 a year, compared with the more than $75,000 a year that British foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh earned in London. With only eight employees, the State Department had a budget of less than $125,000 a yearâone-tenth the budget of the British Foreign Office. Under pressure from President Monroe, Congress raised John Quincy's salary to $6,000 a year in 1819 but gave him no funds to cover his annual entertainment expenses, which totaled about $11,000, or nearly twice his salary.

Monroe himself, of course, had struggled under the same budgetary restrictions as a U.S. minister overseas for six years and as secretary of state for five, and because of his experience in foreign affairs, he involved himself more in State Department business than that of any other executive departmentâwith the warm approval of his secretary of state.

“They were made for each other,” Thomas Jefferson declared. “Adams has a pointed pen; Monroe has judgment enough for both and firmness enough to have

his

judgment control.”

30

As Jefferson predicted, the two men worked so closely and comfortably together and became such intimate friends that John Quincy could anticipate what the President was thinking before the President himself even knew. The warmth that developed between the two men was evident years later, after the President's retirement, when he told Adams, “It would afford me great satisfaction if we resided near each other and could frequently meet and indulge in that free and confidential communication which it was, during our residence in Washington, our practice to do.”

31

his

judgment control.”

30

As Jefferson predicted, the two men worked so closely and comfortably together and became such intimate friends that John Quincy could anticipate what the President was thinking before the President himself even knew. The warmth that developed between the two men was evident years later, after the President's retirement, when he told Adams, “It would afford me great satisfaction if we resided near each other and could frequently meet and indulge in that free and confidential communication which it was, during our residence in Washington, our practice to do.”

31

John Quincy was all too aware, of course, how Secretary of State Jefferson's opposition had undermined President George Washington's neutrality policy, and he was even more cognizant of Secretary of State Timothy

Pickering's unconscionable efforts to undermine the John Adams administration. On taking his constitutional oath and assuming office, John Quincy vowed to be a loyal and effective secretary of stateâadvising the President but allowing him to make all policy decisions and putting those decisions in effect to the best of his ability. “Extend, all-seeing God, thy hand,” he prayed in a poem he wrote the night before he took his oath,

Pickering's unconscionable efforts to undermine the John Adams administration. On taking his constitutional oath and assuming office, John Quincy vowed to be a loyal and effective secretary of stateâadvising the President but allowing him to make all policy decisions and putting those decisions in effect to the best of his ability. “Extend, all-seeing God, thy hand,” he prayed in a poem he wrote the night before he took his oath,

“From the information given to me,” he added, “the path before me is beset with thorns. . . . At two distinct periods of my life heretofore my position has been perilous and full of anxious forecast, but never so critical and precarious as at this time.”

33

33

As it turned out, Louisa's path was as beset with thorns as her husband's. She still displayed a “continental accent,” and Washington's social elite soon referred to the Adamses as “aliens”âespecially after John Quincy began walking in the winter weather wearing his exotic Russian fur hat and great coat. To make matters worse, the Adamses decided to forego the long-standing practice of cabinet members' wives paying the first visit to each member of Congress at the start of each session. John Quincy scorned the practice as a waste of time, and Louisa simply saw no point in soiling herself in the mudflows that separated the buildings and homes of the capital. Although they had bought a lovely home, most of Washington City remained a relative wasteland of woods, swamps, cheap brick buildings, and tumbledown shacks. Seams of squalid slave quarters wove through every neighborhood. Streets were still unpaved, and every rain turned them into vermin-infested marshland that often provoked epidemics. Rats and snakes were commonplace, as were cows, horses, pigs, and other livestock, and Louisa hated stepping outside her door. Washington's ladies were outraged by the snub, however, and even complained to the First Lady. Elizabeth Monroe responded by asking Louisa to the White

Houseânot, as it turned out, to admonish her but to explain the malignity that motivated the customânamely, the ambitions of cabinet members, who sent their wives to court votes in Congress for their husbands to succeed to the presidency. After Washington's retirement, few in the capital expected any presidential candidate to win a majority of Electoral College votes, thus leaving the final decision to the House of Representatives. As a result, candidates' wives made a show of visiting every representative's wife when she and her husband arrived in town.

Houseânot, as it turned out, to admonish her but to explain the malignity that motivated the customânamely, the ambitions of cabinet members, who sent their wives to court votes in Congress for their husbands to succeed to the presidency. After Washington's retirement, few in the capital expected any presidential candidate to win a majority of Electoral College votes, thus leaving the final decision to the House of Representatives. As a result, candidates' wives made a show of visiting every representative's wife when she and her husband arrived in town.

Â

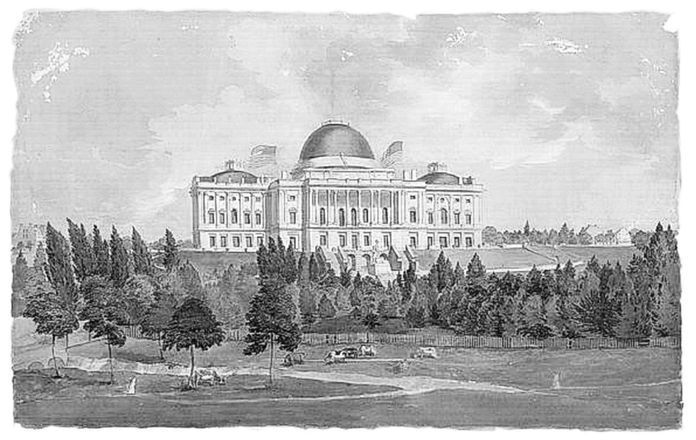

Cows graze near the Capitol in what was still the undeveloped capital city of the United States. At the time, the Supreme Court met in an area beneath the Senate floor.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

“All ladies arriving here as strangers, it seems, expected to be visited by the wives of the heads of departments and even by the President's wife,” John Quincy learned. “Mrs. Madison subjected herself to this torture. . . . Mrs. Monroe neither pays nor returns visits. My wife returns all visits but adopts the principle of not visiting first any stranger who arrives, and this is what the ladies have taken in dudgeon.” Louisa told the President's wife she had no intention of changing her habitsâ“not on any question of etiquette,” John Quincy emphasized, but simply because “she did not exact of

any lady that she should visit her.”

34

Surprised by the controversy over Louisa's visits, an editor questioned John Quincy whether “I was determined to do nothing with a view to promote my future election to the presidency as the successor of Mr. Monroe,” to which John Quincy replied, “Absolutely nothing!”

any lady that she should visit her.”

34

Surprised by the controversy over Louisa's visits, an editor questioned John Quincy whether “I was determined to do nothing with a view to promote my future election to the presidency as the successor of Mr. Monroe,” to which John Quincy replied, “Absolutely nothing!”

He said that as others would not be so scrupulous, I should not stand upon equal footing with them. I told him that was not my faultâmy business was to serve the public to the best of my abilities in the station assigned to me, and not to intrigue for further advancement. I never, by the most distant hint to anyone, expressed a wish for any public office, and I should not now begin to ask for that which of all others ought to be most freely and spontaneously bestowed.

35

35

John Quincy said he had accepted his appointment “for the good of my country”ânot for the good of his career. Although willing to accept higher office, he was determined that the public should decide on his fitness for any office by his record rather than his words. He would soon learn he had adopted a naive approach fraught with enormous political danger.

CHAPTER 11

The Great and Foul Stain

Although the controversy over Louisa's refusal to visit congressional wives persisted for a while, she gradually calmed the social storm by turning her house into a coveted social destination with elegant receptions for illustrious friends from Europe. Washington's ladies (and their men) soon sought invitations to Louisa's Tuesday evening receptions more than to any other social event in Washington. And most gossip about their “alien” tastes ended abruptly when the Adamses hosted a New Year's ball in January 1818 for three hundred guests, who called it the finest Washington festivity in memory. Louisa sparkled in a magnificent gown and emerged as a gracious and ebullient hostess. John Quincy, on the other hand, was a bit of a grouch. Although brilliant at serious gatherings and conferences, his face turned sour when the music began to play and those around him chitchatted and immersed the scene in badinage.

“I am a silent animal,” he grumbled

1

âalthough he usually exuded cheer with his immediate family in private. After the last guests had left one Christmas ball, he broke into a grin and even danced a reel with Louisa and his sons, who were home for the holidays from college.

1

âalthough he usually exuded cheer with his immediate family in private. After the last guests had left one Christmas ball, he broke into a grin and even danced a reel with Louisa and his sons, who were home for the holidays from college.

At the State Department, John Quincy asserted firm authority over his department from the moment he entered. State Department papers had been in disarray since the War of 1812, so he ordered clerks to create an index of diplomatic correspondence and cross-reference every topic in every dispatch and letter to and from overseas consulates and ministries, foreign ministers, and foreign consuls. He then organized and expanded the State Department Library, which became one of the world's largest collections of references and other works relating to foreign affairs. He also assumed an 1817 congressional mandate that directed the secretary of state to report on the systems of weights and measures of various states and foreign countries and to use these to propose a uniform system for the United States. His

Report on Weights and Measures

would take three years to complete, but it became a classic in its field and led to the establishment of the Bureau of Weights and Measures and was the basis for the uniform system that still exists in the United States.

Report on Weights and Measures

would take three years to complete, but it became a classic in its field and led to the establishment of the Bureau of Weights and Measures and was the basis for the uniform system that still exists in the United States.

When he finished the tasks of office management, he turned to foreign affairs policies. Always careful to obtain presidential approval, he issued a standing order that all U.S. ministers abroad adhere firmly to the

alternat

protocol he had championed in London, ensuring that the name of the United States appeared ahead of the other nation on alternating copies of international agreements.

r

alternat

protocol he had championed in London, ensuring that the name of the United States appeared ahead of the other nation on alternating copies of international agreements.

r

Despite peaceful relations with the world's great powers, many stretches along the United States' frontiers seemed at war. Pirates repeatedly attacked American shipping from encampments on Amelia Island in the Atlantic Ocean on the Florida side of the Florida-Georgia border and on Galveston Island in the Gulf of Mexico off the Texas coast. In addition, runaway slaves and Seminole Indians encamped in Spanish Florida were raiding and burning farms and settlements across the border in Georgia. In the North, the British had blocked American access to rich fisheries in and about the Gulf of Saint Lawrence between Newfoundland and the Canadian coast.

Other unsettled issues between Britain and the United States included impressment and Britain's compensation for slaves who had fled to the West Indies at the end of the Revolutionary War.

Other unsettled issues between Britain and the United States included impressment and Britain's compensation for slaves who had fled to the West Indies at the end of the Revolutionary War.

Other books

Corrupt Practices by Robert Rotstein

THE PRESIDENT 2 by Monroe, Mallory

Reflections by Diana Wynne Jones

Stealing Second: Sam's Story: Book 4 in the Clarksonville Series by Clanton, Barbara L.

All or Nothing by S Michaels

Stealing Faces by Michael Prescott

The Course of True Love (and First Dates) by Cassandra Clare

Zonas Húmedas by Charlotte Roche

Bones on Ice: A Novella by Kathy Reichs