Journeyman (19 page)

Authors: Erskine Caldwell

Tom pulled the stopper and offered the jug to Clay. After swallowing several mouthfuls, Clay handed the jug back, wiping his lips with the back of his hand and licking it.

“I hope you aint easily disappointed, Tom,” he said. “I got bad news for you.”

“What’s it about?” Tom asked, drinking from the jug.

“Semon Dye’s up and gone, Tom. He pulled up stakes and left before any of us was up. I reckon he’s way on the other side of McGuffin by now, headed south. I don’t reckon we’ll ever see him again this side of heaven —or hell, which’s more like it.”

“Gone?” Tom said, shaking his head. “You don’t mean to say Semon’s gone, Clay! Ain’t the preacher here now!”

“That’s right. He’s gone.”

Tom set the jug heavily on the porch and looked at it. He glanced at Lorene in the chair by the window.

“That makes me feel real sad,” he said, sitting down beside Clay. He picked up the jug and held it in his arms. “I feel so sad I don’t know what to do about it.”

“Maybe me and you could take the jug and go back to your place and sit in the shed,” Clay suggested. “I sure would like to sit there once more and look through the crack some. It’s one pretty sight for sore eyes.”

Tom pulled the stopper and handed the jug to Clay. When it was returned to him, he looked down through the hole at the colorless liquor and blew his breath into it. It made a sound like wind at night blowing through a gourd tied to a fence post.

Clay reached to the ground for a handful of pebbles. He shook them in his hand, sifting the sand through his fingers. When they were free of sand, he took them one by one, and shot them across the yard like marbles. Tom watched, moving his head back and forth each time one of the little round stones was flicked down the path.

Neither of them turned around to look at Lorene when she got up and walked heavily across the porch and into the hall.

“God help the people at the next place Semon picks out to stop and preach,” Clay said. He flung the remaining pebbles on the ground. “But I reckon they’ll be just as tickled to have him around as I was.”

He got up and walked slowly down the path. When he reached the gate, he stopped for a moment to gaze at the old automobile under the shade of the magnolia tree. Then he went down the road through the hot white sand to tell Sugar to come to the house and start breakfast.

THE END

Erskine Caldwell (1903–1987) was the author of twenty-five novels, numerous short stories, and a dozen nonfiction titles, most depicting the harsh realities of life in the American South during the Great Depression. His books have sold tens of millions of copies, with

God’s Little Acre

having sold more than fourteen million copies alone. Caldwell’s sometimes graphic realism and unabashedly political themes earned him the scorn of critics and censors early in his career, though by the end of his life he was acknowledged as a giant of American literature.

Caldwell was born in 1903 in Moreland, Georgia. His father was a traveling preacher, and his mother was a teacher. The Caldwell family lived in a number of Southern states throughout Erskine’s childhood. Caldwell’s tour of the South exposed him to cities and rural areas that would eventually serve as backdrops for his novels and stories. After high school, he briefly attended Erskine College in Due West, South Carolina, where he played football but did not earn a degree. He also took classes at the University of Virginia and the University of Pennsylvania. During this time, Caldwell began to develop the political sensibilities that would inform much of his writing. A deep concern for economic and social injustice, also partly influenced by his religious upbringing, would become a hallmark of Caldwell’s writing.

Much of Caldwell’s education came from working. In his twenties he played professional sports for a brief time, and was also a mill worker, cotton picker, and held a number of other blue collar jobs. Caldwell married his college sweetheart and the couple began having children. After the family settled in Maine in 1925, Caldwell began placing stories in magazines, eventually publishing his first story collection after F. Scott Fitzgerald recommended his writing to famed editor Maxwell Perkins.

Two early novels,

Tobacco Road

(1932) and

God’s Little Acre

(1933), made Caldwell famous, but this was not initially due to their literary merit. Both novels depict the South as beset by racism, ignorance, cruelty, and deep social inequalities. They also contain scenes of sex and violence that were graphic for the time. Both books were banned from public libraries and other venues, especially in the South. Caldwell was prosecuted for obscenity, though exonerated.

The 1930s and 1940s were an incredibly productive time for Caldwell. He published a number of novels and nonfiction works that brilliantly captured the tragedy of American life during the Depression years. His novels took an unflinching look at race and murder, as in

Trouble in July

(1940), religious hypocrisy, as in

Journeyman

(1935), and greed, as in

Georgia Boy

(1943). In 1937 he partnered with his second wife, Margaret Bourke-White, a photographer, to produce a nonfiction travelogue of the Depression-era South called

You Have Seen Their Faces

.

Through the decades, Caldwell continued to focus his attention on the dehumanizing force of poverty, whether in the South or overseas. Caldwell’s reputation as a novelist grew even as he pursued journalism and screenwriting for Hollywood. He adapted some of his best-known novels into screenplays, including

God’s Little Acre

and

Tobacco Road

, directed by John Ford. As a journalist, he worked as a war correspondent during World War II and wrote travel pieces from every corner of the globe. In 1965 he traveled through the South and wrote about the racial attitudes he encountered in his heralded

In Search of Bisco

.

Caldwell spent much of his later years traveling and writing while living with his fourth wife, Virginia, in Arizona. A lifelong smoker, Caldwell died of lung cancer in 1987.

A baby portrait of Erskine Caldwell. Born December 17, 1903, in White Oak, Georgia, to a Presbyterian minister and a schoolteacher, Caldwell would later describe his childhood home as “an isolated farm deep in the piney-woods country of the red clay hills of Coweta County, in middle Georgia.” (Image courtesy of Dartmouth College Library.)

Erskine Caldwell as a child. With a minister father, Caldwell spent many of his early years traveling the South’s numerous tobacco roads. During these years, he observed firsthand the trials of isolated rural life and the poverty of tenant farmers—themes he would later engage with in his novels. (Image courtesy of Dartmouth College Library.)

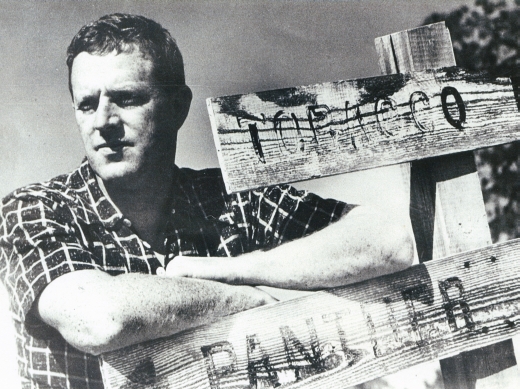

Caldwell’s early novels linked him forever to the Tobacco Road region of the South. This photograph, taken by Caldwell’s second wife, photographer Margaret Bourke-White, references the title of his most famous work,

Tobacco Road

. Published under legendary editor Maxwell Perkins in 1932, the novel was adapted by Jack Kirkland for Broadway, where the play ran for 3,182 performances from 1933–1941, making it the longest-running play in history at that time, and earning Caldwell royalties of $2,000 a week for nearly eight years. (Image courtesy of Dartmouth College Library.)

Publisher Kurt Enoch (left) presenting Erskine Caldwell with the Signet paperback edition of

God’s Little Acre

, published in 1934, the year following its hardcover publication with Viking. Enoch would reprint

God’s Little Acre

fifty-seven times by 1961. The novel was not without controversy: The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice fought to have

God’s Little Acre

declared obscene, leading to Caldwell’s arrest and trial. Caldwell was exonerated, and

God’s Little Acre

went on to sell more than fourteen million copies and see life as a film adaptation in 1958. (Image courtesy of Dartmouth College Library.)

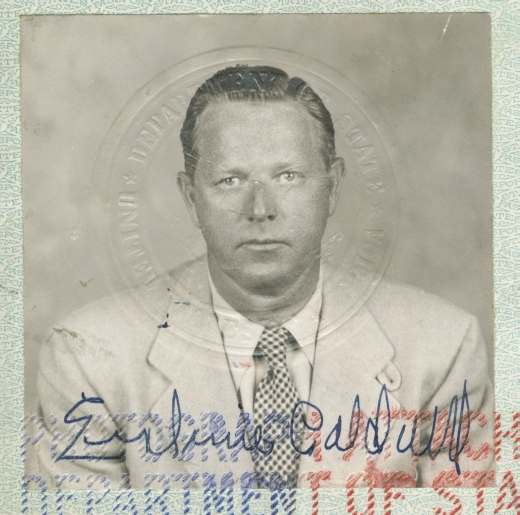

Erskine Caldwell’s passport photo from 1946 to 1950. His occupation on this heavily stamped passport identifies him as a journalist, and he traveled extensively as a reporter throughout his adult life. During World War II, he had received special permission from the U.S.S.R. to travel to the Ukraine, reporting on the war effort there. (Image courtesy of Dartmouth College Library.)