Joyland (23 page)

For three days the pool remained empty. From the top of the tree, the hole seemed even deeper. Ladders hung impotently from the concrete, bottom rungs extending only partway down the blue liner. The deep end plunged away from the shallow — lopsided and dry. In the bottom of the crater, next to the small black plate, two leaves had been sucked together. Their dark wet shapes overlapped on the pale bottom.

The liner was coming out, a new one going in.

In carpenter overalls, Mario ran up and down the platform. Jump the barrel or climb to safety? Options were limited; swiftness imperative. At the top of the screen, Mario’s girlfriend, Pauline, stood patiently beside Donkey Kong. In the arcade version, the word

Help!

wavered over her head. Atari was a cosmos of restrictions. Tammy’s man grasped the ladder, single-runged, too late. The barrel bombarded him. He spun and died. Her second player began again at the bottom of the construction site, repeated the trek up the beams to the building’s roof, where the magnificent digital ape stood beating its chest. On the third floor of scaffolding, Mario snatched the hammer and began to smash the barrels as they rolled toward him. Tammy smiled. In another second, without warning, the hammer disappeared. Just when she was feeling most powerful, she found her player crushed, returned once again to the bottom of the screen.

On the second board, there were fireballs to avoid. But Mr. Lane came over and reduced the screen to fuzz with a flick of his finger before Tammy could make it that far.

“Quit playing this —” he gestured abruptly “— stuff. You’re free. Just don’t wind up in someone else’s kitchen today.” His gaze softened as it fell on Tammy’s face. Mrs. Lane called his name from the other room. He smiled, briefly, the corners of his bottom lip tucking under. “Get outside before we change our minds.”

Workmen, large and beer-bellied, rolled around the edges on their knees, workpants gapping with bum cracks. They shouted out measurements to a younger guy. His ash-brown hair feathered back from his face, but was cut short in a square line at the back, giving his thick white neck the look of an entire country. When they went away, they took the old liner with them in the back of their truck, folded up sloppily, sticking out the gate, like a used maxi-pad rolled in toilet paper, the wet seeping through the tissue. It trailed a thin line of water down the street. Tammy climbed on her bike and followed it all the way to south South Wakefield.

LEVEL 11:

DONKEY KONG JR.

PLAYER 2

Charcoal streaked the air. Porch parties and barbecues echoed through the streets. A couple of kids not much younger than Tammy ran from a plastic turtle pool to their porch in underpants and T-shirts. They flapped their hands and howled. A steady

clink clink

replied as older hands exchanged beer bottles. Screen doors slammed. A jumpy feeling grew inside Tammy as neighbourhood moms began to lean over porch and balcony rails to call their kids in for supper.

She shouldn’t be here.

She should be home.

She looked at her digital watch. Five-thirty was supper without fail at the Lane house, even in the summer. She pedalled slowly up the street, set one foot down at the stop sign, scanned for movement. After the truck had pulled into a small compound with blue siding and wire fencing, the men had been quick to abandon their workplace. The younger one had headed in her direction — walking so snailish, Tammy had been forced to duck into a park to wait before following. Now she had lost him.

She crossed the street and dropped her bike at the curb. She hooked her toes into the wire diamonds of the fence and stood tall.

At one end of the railroad yard, stacks of rusted blue oil drums sat shoulder-to-shoulder. Unlinked cargo cars squatted, some gleaming, others graffitied with desperate messages that would roll across the province and be read at crossings, cargo loaded and unloaded behind those words, in industrial yards in towns both like and unlike South Wakefield:

Brent + Candy

emblazoned in dripping black. Alongside it lay a long metal flatbed —

Eat Shit and Die

scrawled across it. Though the second was written in green, the letters had the same deflated-balloon look. Tammy wondered where Brent and Candy were now. The other end of the field offered nothing but tracks fading into the horizon. Then, a feathered brown head popped up from behind the flatbeds, hoisted its owner up onto the platform, and began to walk the length of the

Brent + Candy

car. He had shed the top of his uniform, now nothing but a white muscle shirt over an obvious mat of chest hair. He was talking to himself. Tammy could tell because he raised one hand and lowered it, shaking it up and down à la Paper-Scissors-Rock.

His shoulders were like bowling balls, and when he turned his head to stare off in the direction of a pink apartment building, Tammy made a positive I.D. by the thick white expanse of his neck. The successful spy quickly mounted her bicycle and sped clandestinely back to the safe house, control.

In her mind she had already taken to calling him the Rabbit, though he was more of an ash-brown ape. The term came from the

Big Book of Spy Terms,

the rabbit being the target in a surveillance operation.

A small pair of portable field glasses had been liberated from the Lane garage. Their twin eyes had been squeezed flat, compact. They lay on the bottom of Tammy’s wire bicycle basket; a brown paper bag (rations) hid them from the top. Tammy had scheduled a lunch break, then a status check of the bubble-pink building that had drawn her impulsive target yesterday. The playground was a cover stop, had Tammy the depth of espionage wisdom to realize it.

Children screamed like seagulls. The bright wavering dots of their T-shirts stretched between the chains of the swing sets. Their running shoes kicked up the sky. Their heads were thrown back. The longest hair dragged in the sand. Tammy headed for the ship-shaped wooden climber in the centre of the park, bumping across the grass. Its strange emptiness ambushed her with gratitude, and she stood on the pedals and pumped hard and fast. She carefully scaled one end, its starboard side a ship’s netting. The spiderweb of chains shook beneath her shoes and pinched her fingers. When she reached the top, she swung over the rail and settled on the log catwalk. She took out an apple and began to eat.

Thirty yards away, teenagers tangled beneath the trees. A skintight girl of jeans in spite of the heat. A shirtless boy of wristbands. The length of her arm became the boy’s; he perused from the tank-top strap down to her wrist, stopped at her hip, sidled closer, snakelike, to make contact with his body, lips. Tammy turned and stared across the park at nothing in particular. The merry-go-round. The bobbing birds held up on industrial coils of wire. The glider on its taut cable, stopped halfway down the tailored incline. Its handles stuck out from its head of gears like a pair of large curved ears. Crunching down on her apple, she wished the couple would go someplace else.

Tammy had kissed a boy — just once — Joshua Grenwald, the final day of fourth grade. She had lost her nerve at the last minute and kissed his cheek, up high beside his ear. Then she had run off across the playground. Sex was an “adult connection, a closeness between a man and a woman.” That was how Mrs. Sturges had described it to Samantha, and how Sam had described it to Tammy. When Sam repeated it, she always rolled her eyes or raised an eyebrow when she intoned the word

closeness.

If it was an adult thing, Tammy reasoned, how come she had never seen adults doing anything even remotely related to it? All they ever did was hold hands. Teenagers were kiss-o-matic, groping in the grass, wandering South Wakefield with fingers stuck in one anothers’ back pockets. Tammy couldn’t remember the last time she had seen her parents kiss.

Suddenly, a soft shuffling. She was not alone on the climber. Tammy turned and surveyed the location. Kids still pumped furiously on the swings, faraway twitters. The sand below her was barren. Her eyes fell on the cabin at the far end of the climber, tucked beneath — a small enclosed area, four feet cubed at most.

She froze, consulted a mental spy guide. Burned, burned, burned. To remain still was stupid. She was out in the open; whoever was inside could see her through the peepholes. So long accustomed to being the passive probe, she could only hope now to become a double agent. From CIA to KGB. With what she prayed would look like confidence, she pitched her apple core through the air toward the garbage can. It fell short, landed in sand. She traversed the catwalk, slid down the fireman’s pole, and peered through one of the holes in the wood into the cabin.

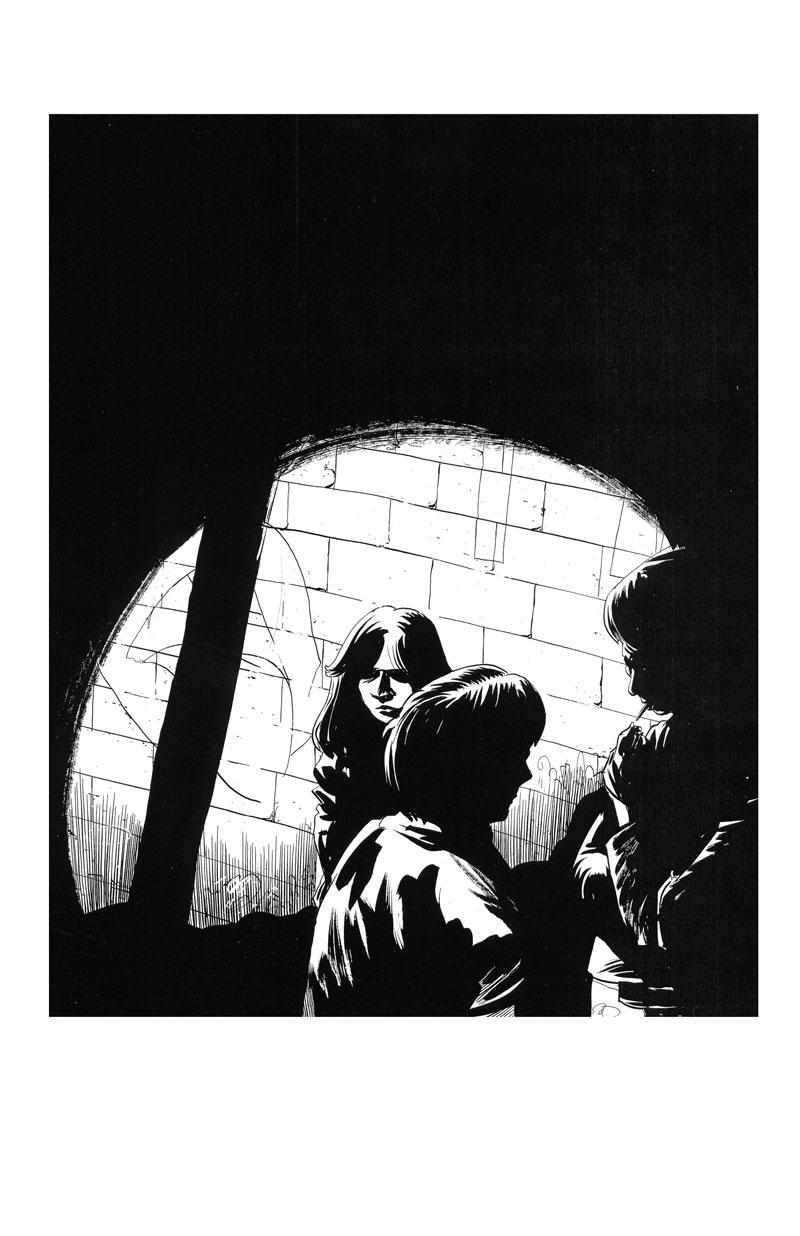

The entire area was taken up by an enormous man. His white T-shirt glowed in the dark half-light, arms folded across his broad chest, and in one of his hands, a tallboy of beer. A running-shoed foot propped just under the eyehole Tammy peered through. They stared at one another. It was him. The Rabbit. The ape-rabbit.

Tammy said, “You’re too big to be in there.”

He didn’t say anything. He took a sip from the can, eyes never leaving hers.

“Don’t you know that’s where little kids go pee?” she said.

Immediately he struggled up, hit his head on the wooden ceiling, crawled slowly out the tiny doorway.

“You’re the pool man,” Tammy said, tentatively. “I saw you from my tree. You were taking measurements for my neighbour’s pool.”

He squinted at Tammy as though he thought he might recognize her. “Sh-i-i-i-i-i-t,” he drawled, and quickly corrected himself. “I — guess so. ’Smy dad’s company.”

“You shouldn’t drink beer in the park.”

The guy shrugged, brushed back wings of bangs. He blew up his lips with a breath for no apparent reason. “Got any more advice for me?”

“Maybe.” Tammy leaned back against the wooden bow. If she were with either Samantha Sturges or Jenny Denis right now, they would have already flown to the opposite end of the park. But Jenny was on vacation. And it was the third time Tammy had encountered the Rabbit in as many days. A sense of purpose filled her, pricked her skin like the splinters in the huge wood beams of the climber. She gave the ship wheel a vigorous spin. “What’s in that big pink building you stand outside?”

The Rabbit’s eyes narrowed. “Why do you follow people?”

No one had asked her this before.

The question sent a thrill of secrecy through her, and the answer — though she did not possess the wizardry to verbalize it — widened the gap between them, giving her a special upper hand.

As they stalked across the railroad yard, Tammy’s bicycle cut a line in the grass. She took four steps to each of his. The pink and blue building bloomed like a scar on the horizon. A girl lived there. The girl. His. The Girl and the Rabbit.

The Rabbit gestured vaguely. “I could take her away from all of this.”

“How?” Tammy asked. When he didn’t say anything — simply extended his hand — she passed him the spy glasses. “She’s a kid and you’re a grown-up.”

He laughed when she said the word

grown-up,

a dead engine sputter, and swore. “How old are you, like, twelve?”

Tammy drew back her shoulders with importance. “Thirteen,” she lied. A year and five months shrivelled up and crept into oblivion.

His eyes were hidden by the miniature binoculars, which, in front of his round face, were even littler. A small smile hung itself on the corner of one stubbled lip.

“You don’t know her.” He didn’t seem to be listening. He lowered the field set. “She’s not like other girls her age. Believe me, I should know. She may look fourteen, but inside . . .” His hand made a poetic twist in the air Tammy interpreted as his lack of language to do her justice, though it could just as easily have been obscenity. He turned toward Tammy and grimaced, an upside-down smile, face full of bewilderment, possibly fear.

“She’s an old soul. Like me.” He tapped his sternum with the baby blue binoculars.

Forgetting her earlier fib, Tammy said, “I play soccer with girls her age.”

He shook his head, unconvinced. He swore again, the sound of it inoffensive, comical, zephyrean. He had a broad, open face that was likeable.

“I’m Pauline,” Tammy said. “What’s your name?”

He extended one meaty paw to shake hands. She hesitated, took it. In comparison, her hand was thin, disk-like, inconsequential as a coin between his fingers. “Adam Granger.”