Jungle of Snakes (10 page)

Authors: James R. Arnold

The insurgents suffered from a crippling lack of firearms and ammunition. Although the Filipinos tried to purchase weapons

from other countries, they were seldom successful. Geography played a role. The U.S. Navy interdicted most vessels trying

to deliver supplies for the insurgents, an operation made easy by the fact that no foreign government became involved in the

supply effort. In addition, the navy prevented cooperation among the Filipino leaders on different islands. The Americans

also benefited hugely from the fact that their enemy had no secure areas, no sanctuaries that were out of bounds to American

intervention.

Throughout the war, the Americans could and did isolate the battlefield and bring overwhelming firepower to bear. This was

not the indiscriminate firepower of a B-52 bomber or a battery of 155 mm howitzers. Rather, it was most often the firepower

of a foot soldier sighting his Krag-Jorgensen rifle. Against the massive American superiority, the guerrillas could conduct

pinprick raids but there was nothing they could do to change the calculus of battle. Their only chance was that the American

public might turn against the war. At first the insurgents invested great hope that Bryan would defeat McKinley. While there

was a spirited anti-imperialist movement at the turn of the century, it never achieved wide political support among voting

Americans.

McKinley’s reelection reduced the anti-imperialists to harassing the administration without being able to change national

strategy. It left the insurgents with only the hope that America would grow war-weary and abandon the struggle. American soldiers

fighting in the Philippines keenly understood the vital importance of domestic support for the war. Brigadier General Robert

P. Hughes, who served as provost marshal of Manila, told the Senate committee that it was the universal opinion of everyone

who went to the Philippines “that the main element in pacifying the Philippines is a settled policy in America.”

15

The Senate Committee in January 1902 asked Taft if a safe and honorable method for withdrawal from the Philippines could be

devised. He replied no and elaborated that at the present moment an assessment of the effort to end the insurgency was too

bound up in politics. However, “when the facts become known, as they will be known within a decade . . . history will show,

and when I say history I mean the accepted judgment of the people . . . that the course we are now pursuing is the only course

possible.”

16

Afterward

While most American historians cite the campaign in the Philippines as an outstanding counterinsurgency success, little mention

is made of what took place after Roosevelt declared the war over on July 4, 1902. Five years after the declaration of peace,

20 percent of the entire U.S. Army still remained in the Philippines. American involvement in the islands was costing American

taxpayers millions of dollars a year in an era when $1 million represented an enormous sum.

The U.S. Army handed responsibility for keeping the peace to the Philippine Constabulary, who found that they had their hands

very full indeed. In all guerrilla wars, the distinction between insurgents and bandits becomes blurred. In the war’s aftermath,

armed men accustomed to preying on the civilian population to obtain their material needs often find it difficult to stop.

Jesse James comes to mind. In the Philippines this class of men were known as

ladrones

, or brigands.

The

ladrones

had been active before the Americans came; some became notable participants in the fight against the Americans, and many continued

to operate after the peace. They imposed their will through intimidation and terror while specializing in rustling, extortion,

and robbery. In the province of Albay, on Luzon’s southern tip, armed resis tance resumed in the middle of 1902. The Americans

insisted on calling them “bandits,” although their numbers peaked at some 1,500 men and they operated according to a military

structure. The “bandits” held out for more than a year in the face of a brutal counterinsurgency campaign fought by members

of the Philippine Constabulary and Philippine Scouts commanded by American officers. Elsewhere, a former guerrilla proclaimed

the “Republic of Katagalugan” with the goal of opposing U.S. sovereignty. He surrendered in July 1906 and was duly executed.

As late as 1910, Constabulary agents in Batangas warned that a shadowy organiza tion whose roots stemmed from the fight against

the Americans was preparing a new insurrection.

In Samar, late in 1902 armed bands again descended from the mountainous interior to raid coastal villages. They were a mix

of

ladrones

, never-say-die common soldiers, and a bizarre mystical sect. The Constabulary fought a losing battle against them until 1904,

at which point the U.S. Army intervened. The subsequent fighting on Samar became so tough that American insurance companies

refused policies to ju nior officers bound for this region. The violence continued until 1911.

Roosevelt’s proclamation of peace had little impact on the Moros, a collection of some ten different ethnic groups who lived

among the southern islands and followed the Islamic faith. They constituted about 10 percent of the Philippine population

and were not racially different from other Filipinos but had been long separated due to their Islamic beliefs. Their conflict

with ruling powers, in particularly Christians and Tagalogs, went back centuries. On Mindanao and Jolo in partic ular, they

battled against the U.S. occupation troops in an effort to establish a separate sovereignty. A three-year campaign involving

Captain John J. Pershing among others officially ended the so-called Moro Rebellion. Yet here too fighting continued past

the official close of the conflict. Indeed, close-quarter combat convinced the army to introduce the Colt .45 automatic pistol

in 1911, a weapon with enough stopping power to drop in his tracks the fanatical Muslim tribesman. Fighting persisted through

1913 but the Moro dream of sovereignty did not die with the advent of peace. This dream again spawned an insurgency in the

1960s, this time directed against the Philippine government. The violence continues to this day as the Moro Islamic Liberation

Front struggles with the Philippine government and Al Qaeda–linked groups maintain training centers on the island of Jolo

and elsewhere.

17

Thus, the dictates of the worldwide “War on Terror” send U.S. Special Forces to the same areas that witnessed the Moro Rebellion.

While the Philippine insurgency still raged, two insightful men, one a war correspondent, the other an army colo nel, contemplated

the future for both Americans and Filipinos. The war correspondent, Albert Robinson, respected the Filipinos and deeply believed

that they deserved self-rule. But he recognized this would not come easily. He thought that aspiring Filipino politicians

lacked balance, a feat achieved in America by virtue of the embedded checks and balances in the Constitution as well as a

cultural tradition. In time, he judged, the Filipinos would acquire this balance, but until that time the United States was

“morally committed” to protecting “against disorder arising out of struggle for leadership.” This protection required American

cultural sensitivity in the form of tact and restraint: “The great danger in American interference in Filipino affairs lies

in the idea that American ways are best and right, and regardless of established habit, custom, and belief, these ways must

be accepted by any and all people.”

18

At the end of 1901 a Colonel who had served as military governor of Cebu wrote eloquently about the possibility that the Philippines

would one day enjoy the American promise of government for and by the people. Toward that lofty goal it was necessary to work

hard to educate the Filipinos about self-government. Such education would take time: “We, and they, will be fortunate if it

be secured in a generation.” He warned that many Americans underestimated Filipino mistrust of Americans and misunderstood

how Filipino nationalism motivated their opposition to U.S. controls. The colonel observed that “too many Americans are inclined

to think the struggle over” and the work of establishing a stable, just government nearly completed. They were wrong, he claimed,

and added that guerrilla warfare would persist for years. He asserted that the correct American response was the sincere promotion

of justice coupled with patience. This goal required the selection of “Americans of character, learning, experience and integrity”

to implement civil government. “The islands are now ours, for better or worse,” he wrote. “Let us make it for the better by

looking the future bravely in the face, without for one moment losing interest in our work. Above all, let it be a national

and not a party question.”

19

During the war almost every unit in the United States Army served at one time or another in the Philippines. Here the army

enjoyed its greatest counterinsurgency success in its history. Yet then and thereafter the army was not particularly enamored

with its victory. Since its birth during the American Revolution, the army had measured itself against conventional Eu rope

an armies. With this mind-set, it viewed the Philippine Insurrection as an exception, something distasteful and outside its

true role. Henceforth, it was more than willing to cede responsibility for fighting the nation’s “small wars” to a rival service,

the United States Marine Corps. So the hard-earned lessons of a nasty fight against Filipino insurgents were quickly forgotten

as army planners refocused on conventional warfare against European foes.

This is not Indochina. This is not Korea.

But it is a nasty piece of work.

—A French captain on patrol in Algeria

1

The French Challenge

IN 1827 THE DEY OF ALGIERS ALLEGEDLY struck the French consul with a fly whisk. The insult provided a con venient pretext

for France to maintain a naval blockade of Algiers. The failure of economic pressure, the blockade, and the failure of “diplomacy”

in the form of three years spent ineffectually plotting to overthrow the uppity dey convinced French leaders to invade Algeria

in 1830. They explained to the natives that they came not to war against the people but rather to expel their Turkish rulers

and allow the Arabs to be masters of their own country. In fact, politicians in France had concluded that a foreign military

adventure would solidify army support for the restoration regime of Charles X. This calculation proved erroneous. A few weeks

after the invasion Charles X’s regime fell. But by then the French army controlled Algiers and its leaders were eager to colonize

the rest of the country. It was a decision that led to an occupation that lasted for the next 132 years.

Before the French invaded, the country the French called Algeria had no history of nationhood or self-rule. The Carthaginians,

Romans, and Vandals all preceded the Arab conquest that came in A.D. 643. Before the sixteenth-century Ottoman conquest, the

western part of Algeria was often closely associated with Morocco while the eastern part followed the lead set by Tunisia.

The few home-grown Muslim dynasties that developed in Algeria did not last long. However, history, language, custom, and the

practice of Islam made the native people an integral part of the larger Arab world.

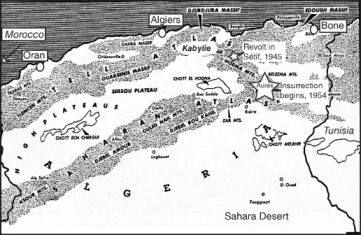

All would-be rulers discovered that geography made Algeria a difficult country to control. It had an area three times the

size of Texas. Large mountain chains formed barriers to north-south communication. The formidable Sahara Desert extended along

Algeria’s southern border, while the lack of good natural harbors along the Mediterranean shoreline limited access from the

sea to the hinterlands. Most people lived along the Mediterranean coastal strip, where fertile soil and rain allowed agriculture,

and it was here that the Europeans settled as well.

From the beginning many of the natives resented the French presence. A series of rebellions against the “Christian invasion”

failed, but the embers of revolt remained to ignite subsequent struggle. The inhabitants of the rugged Kabylie (or Kabylia),

a non-Arab regional minority, proved particularly difficult to subdue. Not until 1871 did the French suppress their last,

great rebellion. Thereafter, for an elite subset of French bureaucrats and military officers, the preservation of the conquest

became a profound matter of honor.

The elimination of native resistance and confiscation of the best land opened the way to Eu rope an colonization. Thousands

came from Spain to live around the great port of Oran, while Italians, Maltese, and French settled farther east around Algiers

and Bone. But in the eyes of French administrators, Algeria was destined to be a French colony pure and simple. In 1848 settlers

converted the three Turkish provinces to departments on the French model and colonization expanded rapidly. The colonists

soon established political, economic, and social domination. The Arabs who saw the first French settlers arrive collectively

nicknamed them

piedsnoirs

(black feet), apparently in reference to their wearing black leather shoes. The

piedsnoirs

modernized Algeria, building roads, railroads, hospitals, and schools where select natives were allowed to learn French language,

history, and culture. The Europeans created prosperous agricultural plantations along the Mediterranean coast where grains,

olives, and grapes grew in a favored environment of fertile soil, sun, and water. By 1945, some 1 million Europe ans, of whom

fewer than 20 percent were of pure French descent, lived in Algeria. By now Algeria was jurisdictionally a part of France,

which added to the power of the

piedsnoirs

since they sent delegates to the French parliament. For most

piedsnoirs

, particularly those on the top rungs of the economic ladder, life was good and the future appeared bright.

The Rise of the FLN

In 1945 thousands of Muslim inhabitants of the Algerian town of Sétif revolted against French rule and massacred more than

100 Europe an settlers. In French eyes the attack was unprovoked. The French military responded with brutal repression, subjecting

suspect Muslim villages to systematic punishment called

ratissage

, literally a “raking-over.” An unknown number of killings ensued, with the total undoubtedly higher than the official French

report of 1,800. It proved a watershed moment. The excessive French reprisal alienated a population that might not otherwise

have sided with the rebels. A liberal Algerian poet, Kateb Yacine, was sixteen years old at the time. He spoke for the Muslim

majority when he recalled that the “pitiless” French reprisal marked the “moment my nationalism took definite form.”

2

Although largely unnoticed by the general population in France, the Sétif incident alarmed the French political class. In

1947 the French assembly passed a new “bill of rights” for Algeria. It responded to Muslim demands with important reforms

including the recognition that Muslims would be considered as full French citizens with the right to work in France. However,

the creation of an Algerian assembly with 120 deputies revealed the maintenance of colonial rule. Some 370,000 Eu rope ans

and 60,000 “assimilated” Muslims elected half the deputies. The country’s other legal voters, some 1.3 million Muslims, also

elected half of the deputies. Thus, the Algerian assembly was a far cry from representative government. Moreover, the

pieds-noirs

blocked the implementation of most reforms. The 1948 elections for the new Algerian assembly featured widespread fraud. Subsequently,

9 million native Algerians, most of whom were Muslim, understood that the legal path to reform was closed to them.

Pied-noir

intransigence drove them toward the path of violence.

There were several nationalist movements inside Algeria but only one advocated the use of all necessary means to end French

rule. This movement coalesced into the Front de libération nationale (FLN). The typical FLN leader was a male in his early

thirties, of modest origin, education, and prospects. Many, like Ahmed Ben Bella, the man who became the movement’s principal

leader, were former members of the French army. Some had returned from World War II festooned with French military medals.

Ben Bella had earned the Croix de Guerre in 1940 and the Médaille Militaire in 1944. Ben Bella and his fellow combat veterans

contrasted their war experience—the equality of shared danger in the bitter mountain fighting against German fortifications

during the Italian cam-paign—with the open discrimination they found in postwar Algeria. Ben Bella was among the many who

saw the rigged election of 1948 as final proof that any hope of achieving in dependence at the voting booth was illusory.

The revolutionaries did not view the world according to a set political ideology. What united them was opposition to French

rule. What separated them from the thousands of similar men who lived in Algeria during the 1950s was their willingness to

fight to the finish to accomplish this goal and their willingness to sacrifice their lives. The FLN objective was the restoration

of a sovereign Algerian state. It advocated social democracy within an Islamic framework.

When FLN leaders contemplated strategy they appreciated that the Communist Chinese formula for anticolonial insurgencies began

with the creation of a strong revolutionary party. The construction of this necessary foundation took time. Once the foundation

was set, the revolutionary front could proceed to terrorist violence and initiate guerrilla warfare. The ensuing disruption

would produce opportunities to acquire base areas, or liberated zones. Here the front would organize a regular army to begin

conventional war.

The insurgent leadership in Algeria were impatient strategists. They decided to take a shortcut by beginning with violence

and seeing what ensued. In the spring of 1954, Ben Bella and other Algerian nationalists convened in Cairo, where, with the

full support of the aspiring leader of the pan-Arab nationalist movement, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, they formed

the Revolutionary Committee for Unity and Action. The committee ignored existing Algerian nationalist groups and instead decided

on bold, decisive action to drive the French out of Algeria and install themselves in power.

An event in faraway Vietnam, the surrender of the French garrison of Dien Bien Phu on May 7, 1954, after an epic fifty-six-day

siege, galvanized Algerian militants. Before, only a handful of nationalists supported the notion of military struggle with

France. The task seemed too daunting. Dien Bien Phu demonstrated French vulnerability and emboldened Algerians to conceive

that they could successfully fight their way to in dependence. Using the French Resis tance as their model, FLN leaders prepared

an Alge-rian resis tance movement. It relied on one military weapon and one political weapon. The military weapon was domestic

guerrilla warfare featuring hit-and-run raids, ambushes, and sabotage. The political weapon relied upon the international

climate that in the wake of World War II nominally favored self-determination. The FLN intended to assert the right of self-determination

on the international stage, particularly at the United Nations. FLN leaders expected this assertion to garner support from

other Arab nations. They also intended to capitalize on Cold War schisms to receive support from the Communist bloc.

FLN leaders selected the Aurès massif, a mountain chain extending across eastern Algeria, as the most promising region to

launch their campaign. The rugged Aurès mountains, with their razorback ridges separated by deep ravines and scattered pine,

live oak, and cedar forests, were a traditional refuge for men fleeing invaders or the law. Even by Algerian standards the

Aurès was a poverty-stricken region where subsistence farmers lived in mud-daubed villages. Banditry was nearly as common

as sheep herding. Three times in the past hundred years the Aurès had revolted against the French. The FLN calculated that

such people would happily support a fourth revolt. Moreover, a native revolutionary of the region, Belkacem Krim, already

had an organized and armed guerrilla band hidden in the heartland of the Aurès mountains. Better still, in 1954 in all the

massif only seven gendarmes were present to represent French law.

Couriers carried instructions across Algeria: “Arm, train and prepare.” In the crowded Muslim quarter of Algiers, the infamous

Casbah, a dedicated terrorist named Zoubir Bouadjadj set up a network of bomb-making factories. Elsewhere, insurgents smuggled

firearms past police outposts, everything from World War I–era bolt action rifles to weapons carelessly lost by American GIs

during the 1942 invasion of North Africa. Most fighters had to be content with unreliable hunting guns better suited for shooting

a feral goat than a French regular.

The effort to create a revolutionary infrastructure without solid preparation did not work. Recruitment for the

djounoud

, the “soldiers of faith,” failed to attract many candidates; most people chose to wait and see what happened before choosing

sides. The FLN leadership cared not. Inspired by news of French failure in Indochina, they wanted to strike while opportunity

beckoned. D-Day for the simultaneous outbreak of rebellion would be one minute after midnight on November 1, 1954, the day

France, and most especially the staunchly Catholic

pieds-noirs

, celebrated as All Saints’ Day.

The Counterinsurgency Begins

During World War II, diverse French political parties had forged bonds of mutual self-interest in order to oppose the Germans.

After the war those bonds became unstable as shaky coalition governments collapsed one after another. Military men disdainfully

spoke of striving politicians while French citizens took solace in the fact that a strong and competent bureaucracy administered

the country regardless of the political circus at the top. However, short-lived Oalitions could not muster a coherent national

response if trouble arose in the colonies. The postwar rise of nationalism in Africa brought that trouble barely six months

after Dien Bien Phu’s surrender.

The number of Algerian rebels who participated in the All Saints’ Day revolt probably did not exceed 700. They conducted seventy

simultaneous attacks at scattered places throughout Algeria, killing seven people and wounding four. This was hardly a devastating

blow. It made a minimal first impression in France, where few suspected that a war had begun. Indeed, the rebels lacked firearms,

their homemade explosive devices were unreliable, and there were simply too few insurgents ready to start fighting. The poverty

of resources was such that although the FLN leaders had ambitiously divided Algeria into six military-political districts,

or

wilayas

, for almost a year following the All Saints’ Day revolt three of the district chiefs had neither followers nor weapons.