Jungle of Snakes (3 page)

Authors: James R. Arnold

Following the Spanish surrender, a state of high tension persisted for almost half a year. About 14,000 American soldiers

established a perimeter defending Manila and worked fitfully to make the city a showcase for the benefits of benign assimilation.

Meanwhile, Aguinaldo’s newly named Army of Liberation, with about 30,000 soldiers, maintained a loose cordon around the city

while Aguinaldo, who felt betrayed by American conduct, prepared for war. He and his

insurrectos

, as the Americans labeled them, did not intend to exchange one colonial master for another. Aguinaldo warned that his government

was ready to fight if the Americans tried to take forcible possession of insurgent-controlled territory. Operating under McKinley’s

assumption that it was only a matter of time until Filipinos came to their senses, the American commander of ground forces,

General Elwell Otis, avoided provoking the insurgents. Finally the inevitable occurred on the evening of February 4, 1899,

when a shooting incident escalated into war.

The next day President Aguinaldo issued a proclamation to the Philippine people announcing the outbreak of hostilities. It

explained that he had tried to avoid conflict, but “all my efforts have been useless against the measureless pride of the

American Government . . . who have treated me as a rebel because I defend the sacred interests of my country.”

3

On the Brink of Victory

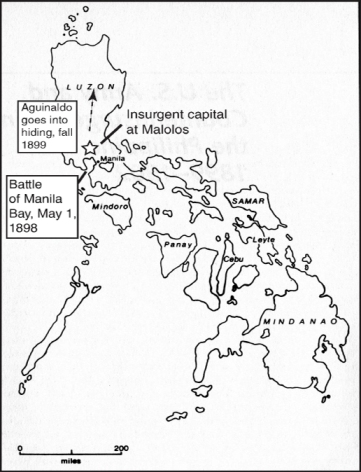

The Philippine-American War had two distinct phases. During the first, conventional phase, from February to November 1899,

Aguinaldo’s soldiers operated as a regular army and fought the Americans in stand-up combat. In the absence of a coherent

strategy—the revolutionary cause never bred a first-class strategist; Aguinaldo proved himself in deep over his head as a

military thinker—Filipino efforts focused on defending the territory they controlled. This defense lacked imagination, amounting

to little more then trying to position units between the Americans and their objectives. The U.S. Army easily dominated the

conventional war. The army could reliably find the enemy and bring him to battle. Once combat began, the army’s superior firepower

dominated. The contest was so one-sided that General Otis reported that he could readily march a 3,000-man column anywhere

in the Philippines and the insurgents could do nothing to prevent it. Conventional military history taught that when one side

could not oppose the free movement of its enemy across its own territory, the war was all but over. Indeed, military pressure

coupled with the army’s commitment to a policy of benevolent assimilation appeared to produce decisive results in the autumn

of 1899, as Otis prepared a war-winning offensive scheduled to take advantage of Luzon’s dry season.

Otis worked very hard but wasted endless time supervising petty details. A journalist observed that Otis lived “in a valley

and works with a microscope, while his proper place is on a hilltop, with a spy-glass.”

4

MacArthur was even less charitable, describing the general as “a locomotive bottom side up on the track, with its wheels

revolving at full speed.”

5

Unfortunately, members of the Filipino elite living in Manila had the measure of the man and they told Otis what he wanted

to hear, namely, that most respectable Filipinos desired American annexation. This fallacy reinforced Otis’s instinct toward

false economy, to cut corners and win the war without expending too many resources.

His plan to capture the insurgent capital in northern Luzon and destroy Aguinaldo’s Army of Liberation was akin to a game

drive writ large. One group of Americans acted as beaters, herding the Filipinos toward the waiting guns of a blocking force

that had hurried into position to intercept the fleeing prey. By virtue of prodigious efforts—unusually heavy rains flooded

the countryside, reducing one cavalry column’s progress to sixteen miles in eleven days—American forces broke up the insurgent

army, captured supply depots and administrative facilities, and occupied every objective. As if to confirm what the Manila

elite had told Otis, soldiers entered villages where an apparently happy people waved white flags and shouted, “

Viva Americanos.

”

An American officer, J. Franklin Bell, reported that all that remained were “small bands . . . largely composed of the flotsam

and jetsam from the wreck of the insurrection.”

6

Otis cabled Washington with a declaration of victory. He gave an interview to

Leslie’s Weekly

in which he said: “You ask me to say when the war in the Philippines will be over and to set a limit to the men and trea sure

necessary to bring affairs to a satisfactory conclusion. That is impossible, for the war in the Philippines is already over.”

7

It certainly appeared that way to eighteen-year-old George C. Marshall. The volunteers of Company C, Tenth Pennsylvania, returned

from the Philippines to Marshall’s hometown in August 1899. Marshall recalled, “When their train brought them to Uniontown

from Pittsburgh, where their regiment had been received by the President, every whistle and church bell in town blew and rang

for five minutes in a pandemonium of local pride.” The subsequent parade “was a grand American small-town demonstration of

pride in its young men and of wholesome enthusiasm over their achievements.”

8

Victory enormously pleased the McKinley administration. Now benevolent assimilation could proceed unhindered by ugly war.

The president told Congress, “No effort will be spared to build up the vast places desolated by war and by long years of misgovernment.

We shall not wait for the end of strife to begin the beneficent work. We shall continue, as we have begun, to open the schools

and the churches, to set the courts in operation, to foster industry and trade and agriculture.” Thereby the Filipino people

would clearly see that the American occupation had no selfish motive but rather was dedicated to Filipino “liberty” and “welfare.”

9

In fact, Otis and other senior leaders had completely misjudged the situation. They did not perceive that the apparent disintegration

of the insurgent army was actually the result of Aguinaldo’s decision to abandon conventional warfare. Instead, the ease with

which the army occupied its objectives throughout the Philippines brought a false sense of security, hiding the fact that

occupation and pacification—the pro cesses of establishing peace and securing it—were not the same at all. A correspondent

for the

New York Herald

traveled through southern Luzon in the spring of 1900. What he saw “hardly sustains the optimistic reports” coming from headquarters

in Manila, he wrote. “There is still a good deal of fighting going on; there is a wide-spread, almost general hatred of the

Americans.”

10

Events would show that victory required far more men to defeat the insurgency than to disperse the regular insurgent army.

Before the conflict was over, two thirds of the entire U.S. Army was in the Philippines.

How the Guerrillas Operated

Otis’s offensive had been final, painful proof to the insurgent high command that they could not openly confront the Americans.

Consequently, on November 19, 1899, Aguinaldo decreed that henceforth the insurgents adopt guerrilla tactics. One insurgent

commander articulated guerrilla strategy in a general order to his forces: “annoy the enemy at different points” while bearing

in mind that “our aim is not to vanquish them, a difficult matter to accomplish considering their superiority in numbers and

arms, but to inflict on them constant losses, to the end of discouraging them and convincing them of our rights.”

11

In other words, the guerrillas wanted to exploit a traditional advantage held by an insurgency, the ability to fight a prolonged

war until the enemy tired and gave up.

Aguinaldo went into hiding in the mountains of northern Luzon, the location of his headquarters secret even to his own commanders.

He divided the Philippines into guerrilla districts, with each commanded by a general and each subdistrict commanded by a

colonel or major. Aguinaldo tried to direct the war effort by a system of codes and couriers, but this system was slow and

unreliable. Because he was unable to exercise effective command and control, the district commanders operated like regional

warlords. These officers commanded two types of guerrillas: former regulars now serving as full-time partisans—the military

elite of the revolutionary movement—and part-time militia. Aguinaldo intended the regulars to operate in small bands numbering

thirty to fifty men. In practice, they had difficulty maintaining these numbers and more often operated in much smaller groups.

The lack of arms badly hampered the guerrillas. A U.S. Navy blockade prevented them from receiving arms shipments. The weapons

they had were typically obsolete and in poor condition. The ammunition was homemade from black powder and match heads encased

in melted-down tin and brass. In a typical skirmish, twenty-five rifle-armed guerrillas opened fire at point-blank range against

a group of American soldiers packed into native canoes. They managed to wound only two men. An American officer who surveyed

the site concluded that 60 percent of the insurgents’ ammunition had misfired. Although the insurgents typically had prepared

the ambush site complete with their guns mounted on rests, their shooting was also notoriously poor. Not only did they lack

practice because of the ammunition shortage but also they did not know how to use both the front and back sights on a rifle.

Insurgent officers were painfully aware of their deficiencies in armaments. One colonel advised a subordinate to arm his men

with knives and lances or use bows and arrows. Another pleaded with his superiors for just ten rounds of ammunition for each

of his guns so that he could attack a vulnerable American position. On the offensive the regulars carefully chose their moment

to strike: a sniping attack against an American camp or an ambush of a supply column. After firing a few rounds they withdrew.

On the defensive they seldom tried to hold their ground but instead dispersed, changed to civilian clothes, and melted into

the general population.

The part-time militia, often called the Sandahatan or bolomen (the latter term referred to the machetes they carried), had

different duties. They provided the regulars with money, food, supplies, and intelligence. They hid the regulars and their

weapons and provided recruits to replenish losses. They also acted as enforcers on behalf of the government the insurgents

established in cities, towns, and villages. The civilian arm of the insurgent movement was as important as the two combat

arms. Civilian administrators acted as a shadow government. They ensured that taxes and contributions were collected and moved

to hidden depots in the hinterland. In essence, the network they created and managed constituted the insurgents’ line of communications

and supply.

From the insurgent standpoint, the decision to disperse and wage guerrilla war placed the fate of the revolution in the hands

of the people. Everything depended on the people’s willingness to support and provision the insurgency. Guerrilla leaders

well understood the pivotal importance of the people. They decreed it was the duty of every Filipino to give allegiance to

the insurgent cause. Ethnic and regional loyalty, genuine nationalism, and a lifelong habit of obeying the gentry who composed

the resis tance leaders made many peasants accept this duty.

If the insurgents could not compel active support, they absolutely required silent compliance, because a single village in

formant could denounce an insurgent to the Americans. The guerrillas invested much effort to discourage collaboration. When

appeals to patriotism failed, they employed terror. A prominent revolutionary journalist urged the infliction of “exemplary

punishment on traitors to prevent the people of the towns from unworthily selling themselves for the gold of the invaders.”

12

One of Aguinaldo’s orders instructed subordinates to study the meaning of the verb

dukutar

—a Tagalog expression meaning “to tear something out of a hole” and widely understood to signify assassination.

13

Thereafter, numerous orders flowed from all levels of the insurgent command authorizing a full range of terror tactics to

prevent civilians from cooperating with the Americans: fines, beatings, or destruction of homes for minor offenses; firing

squad, kidnapping, or decapitation for Filipinos who served in American-sponsored municipal governments. However, the revolutionary

high command never advocated a strategy of systematic terror against the Americans. They wanted to be recognized as civilized

men with legitimate qualifications for running a civilized government and so limited terror to their own people.

As the war continued, civilians became the partic u lar victims even though most Filipino peasants actively supported neither

the guerrillas nor the Americans. As long as neither side incurred their wrath via excessive taxation, theft, destruction

of property, or physical coercion, they simply continued with their daily chores and hoped that the conflict would be played

out elsewhere.