Kate Berridge (4 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

The waxworks were the ideal forum to cater for a phenomenal human interest in public figures that was distinct from respect for their work. In fact cultural achievement was not necessary at all to appear there: the admission requirement was to have attained sufficient public interest to guarantee a crowd; notoriety was as compelling as admiration. From the recently executed criminal to society beauties, Curtius guaranteed a close-up view of the most talked-about people of the day. As each person had their time in the spotlight of public interest, they would take their turn in his pantheon.

The new dynamics of fame fuelled by the growing power of public opinion meant that the elite private salon was shrinking in stature, and was being influenced from the outside. Madame de La Tour du Pin describes how Voltaire and Rousseau, the most famous â

philosophes

', though not actually present at the most select salons run by those who moved in court circles, greatly influenced these circles, and discussion of their ideas animated these august gatherings. Certain aspects of these changes were less welcome. Rousseau was uneasy about the advent of a new fan base which made him, not his work, the focus of people's interest:

I met people who had no taste for literature, most of whom had not even read my works, but who nonetheless, from what they told me, had travelled a hundred, or three hundred miles in order to see and admire the illustrious man, the celebrated man, the most celebrated man: so I waited for them to start conversation, since it was up to them to know and to inform me why they had come to see me. Naturally this did not lead to discussions which interested me very much, though they may have interested them.

This anticipates the contemporary complaint of celebrities who compare fame to the one-sidedness that comes with amnesia or Alzheimer'sâthey are surrounded by people who seem to know everything about them, while they don't have a clue who these people are.

Rousseau's influence showed that intellectual ideas were as capable of being vulgarized as fine clothes. Tear ducts nearly ran dry during the success of his

La Nouvelle Héloïse

, a sentimental novel published in the year Marie was born. A national and international best-seller, reprinted many times throughout the century, this epistolary alpine romance charting the turbulent and tragic events when true love between a lowly tutor and a noble heroine is thwarted by aristocratic prejudice tapped a collective romantic nerve. In a letter to the author, Baron de La Sarraz confessed that he had had to read the book in private so that he could have a really good cry without being interrupted by his servants. Another fan sobbed, âOne must weep, one must write to you that one is choking with emotion and weeping.'

The upshot was that emotional correctnessâa need to be seen to be sensitiveâbecame de rigueur. At a performance of a new opera by Gluck (

Iphigénie en Aulide

, in 1774), to avoid the faux pas of being perceived to be insensitive Baron de Grimm took the precaution of shedding ostentatious amounts of tears throughout the entire performance. Even letter-writing styles gushed sentimentality, and the Queen was not immune to this trend, signing off letters to friends with the flowery flourish, âA heart entirely yours'.

Rousseau also sparked a white-food fadâspecifically for milk dishes that hinted at a delicate constitution, while evoking the rustic charms of cows and the wholesome delights of the Swiss countryside.

That a serious thinker influenced not only what people thought but what they bought was an innovation. His influence spanned a spectrum of fashions from wallpaper designs to hairstyles. The headdress called a

pouf

involved an elaborate assembly of horsehair padding and false hair all bound together and accessorised with a variety of trimmings including a small bonnet precariously perched on top. The â

pouf de sentiment

' required the wearer to use her hairstyle to display her individuality in the best Jean-Jacques fashion by incorporating as many personal references as could be fitted on her head. Objects used to achieve this effect included stuffed birds, small dolls, flowers and foliageâall carefully arranged and attached with pins, gauze and pomatum (a strong scented paste). The Duchesse de Chartres set an impossibly high standard with the effort and detail of the biographical allusions she wore in her hair. Towards the back of her head was an image of her son with his wet nurse, to the right a replica of her pet parrot shown picking at a cherry, to the left a doll representing her favourite serving boy. The ensemble also included locks of hair from the men in her life including her husband, the Duc de Chartres, her father and her father-in-law.

Although not all women went to such lengths in their homage to the great philosopher, the fad for expressing personality via one's coiffure resulted in some extraordinary creations, as observed by one of the most famous hairdressers of the day, Léonard: âI saw poufs containing the strangest fantasies of caprice. Frivolous women strewed their heads with butterflies. Sentimental women nestled swarms of Cupids in their hair; the wives of officers wore squadrons of horses perched upon the front of their head; women of melancholic mood had poufs constructed of coffins and funeral urns.'

Curtius's genius was to give these changing facets of society tangible shape in the form of characters in his public exhibition. From his earliest arrival in the city, when still under the wing of his noble patron, he had been perfectly placed to exploit the burgeoning passion for fashion that was such an important catalyst in an emerging culture of impermanence. His combination of commercial aptitude and flair for cultivating influential people echoes the career trajectory of Rose Bertin, who shared his entrepreneurial brio. It is little surprise that their paths crossed. In one of his most astute moves,

when both their careers were booming he is said to have commissioned Bertin to supply couture costumes for his wax figure of Marie Antoinette that replicated what she had designed for the Queen.

Of course it is important not to overstate the extent of cultural transformation that was happening as Marie grew up. While concepts of social equality, religious tolerance and political liberty achieved an unprecedented prominence, being discussed and debated as never before, this happened against a background of vast social, economic and doctrinal division which even the Revolution would only briefly disrupt and would by no means eradicate. Nevertheless, Curtius's understanding of the dynamics of the new marketplace for fame, the power of publicity, and the commercial potential of a nascent mass marketâparticularly among the affluent middle classâwas an integral part of his success. There was no more accurate index of what the public wanted than Curtius's waxworks. His exhibitions were the ultimate democratic cultural institutions. Although ostensibly looking at other people, when the people of Paris stared at the life-size figures in his salon they were looking into a new mirror of their own taste, aspirations and values.

At every turn Curtius capitalized on the growing interest in the here and now. Whereas formerly official culture would reinforce the status quo and precedence and tradition shaped artistic forms, now a new value was attached to novelty and change, and nowhere was this expressed more clearly than by the changing roster of waxen beauties, aristocrats, artists and villains. In the new marketplace, fame was transient. Becoming a household name was one thing, but in a society where taste was like a weathervane and people could come and go out of fashion, remaining famous was an altogether different challenge. Mercier summarized the wide-ranging market for novelty:

It is altogether correct to be mad for novelty, new dishes, new fashions, new books to say nothing of a new actress or opera; as for a new way of dress or hair, it is enough to set the whole crew of fashionables raving. The novelty, whatever it may be, spreads in the wink of an eye as though all these empty heads were electrified. It is the same with people: some man of whom nobody has previously taken the least notice suddenly becomes the rage and lasts six months, after which they drop him and start some other love.

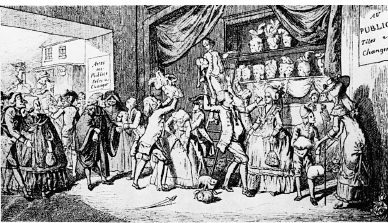

âChange the Heads!', cartoon by P. D. Viviez 1787

For Curtius this dropping was a matter of chiselling the head off a model and replacing it with a freshly moulded face of someone whom the public were more interested in. This ignominious head-chopping was a brutal index of the fickle nature of the public, who demoted with equal dispassion the people whom with enthusiasm they had once elevated to glory. It was also morbidly portentous.

The path of Curtius's career echoes the changing mechanics of patronage. Instead of depending on a privileged system of patronage centred on a specific physical space such as the court or a private salon, artists, writers and performers now increasingly relied on recognition from the general public. The German playwright Schiller articulated the essence of this change when he described the public as âmy preoccupation, my sovereign and my friend', and exclaimed, âThe only fetter I wear is the verdict of the world.' While Curtius started out with an aristocratic patron who nurtured his talent and for whom he undertook commissions within polite society, it was being taken up by the general public that sealed his reputation. His success was such that by the time of de Conti's death, in 1776, he had made significant inroads in the burgeoning field of commercial entertainment and had a presence both at the fairs and in the bustling boulevards. The dates when he opened the different

branches of his enterprise are hard to pinpoint, but in rough chronological order he had two small exhibitions at the great fairs of Paris, Saint-Laurent and Saint-Germain, a permanent exhibition at 20 Boulevard du Temple (where he also had his workshop and family home) and finally his most famous and fashionable exhibition, the Salon de Cire in the Palais-Royal, part of the estate of the Duc d'Orléans. It was this site that made Curtius's name. He rented premises here from its controversial redevelopment as a shimmering complex of arcades, cafés and entertainmentsâa new kind of urban amenity in the early 1780sâuntil just before the turbulent events of 1789, when he consolidated his various activities in one exhibition in the Boulevard du Temple.

Curtius was a chameleon, both personally and professionally, as happy in catering for the sensation-seekers paying a few sous at the fair as he was in satisfying lucrative private commissions. He always took great pains to adapt the content of the exhibition to circumstances. At the fairs his exhibitions were arranged more in the style of a cabinet of curiosities, with an eclectic mixture of unusual objects and artefacts alongside the waxworks. This was the world of the freak and the hoax, where the more outlandish the dimensions, afflictions and claims of any attraction, the better the takings. By painting a monkey's face and gluing a false horn to it, a menagerie could proudly present a new species from Peru. Sometimes the best-laid plans to present a genuine animal as yet unseen in Paris went wrong, as happened to unfortunate Monsieur Ruggery, who had hoped to make a killing with a very rare animal billed as the âTarir of L'Auta from America'. The poor creature died en route, but so keen was Monsieur Ruggery not to disappoint that, as he announced on his posters, he had him âstuffed with the greatest care by Monsieur Mauvé'.

If animals were commonly presented as more exotic than they really were, then so too were peopleâthe vast majority of âgiants' were actors in five-inch heels, long skirts and tall wigs. Chez Curtius the showman, it was the wonder of the real that amazed, the famous and infamous replicated exactly as they were, and those who came could not believe their eyes. This milieu was loud and louche, a din and a scrum of unsophisticated pleasures, a tawdry, tacky playground. That Curtius was there at all shows he was far less socially squeamish

than Marie, who as an adult loathed the association of waxworks with the fair. Several notches up in tone was his exhibition in the Boulevard du Temple.

This district was the eighteenth-century Parisian equivalent of Broadway or the West End, the geographical home of popular entertainment, with spectacular shows featuring acrobats and circus entertainments, magic and mystery as well as popular theatre. Here Curtius showed villains alongside his wax heroes. The Caverne des Grands Voleursâliterally the Cave of the Great Thievesâwas a show within a show, the forerunner of the Chamber of Horrors. Melodramatic special effects set the tone, with blue light casting the criminals in a lurid otherworldly hue and, as a ghoulish garnish, fake blood. A contemporary account by Louis de Bachaumont states, âAs soon as Justice has dispatched someone Curtius models the head and puts him into the collection so that something new is always being offered to the curious, and the sight is not expensive for it only costs two sous. The barker shouts, “Come in, Messieurs, come and see the great thieves.” '

Curtius discovered that crime paid. The Caverne des Grands Voleurs was an ingenious way of exploiting the public love of a juicy murder and a dramatic execution. Crime and punishment were topics of perennial interest, and being well informed about them earned you street credibility. As Mercier said, âSome worthy cobbler, for instance, will know the history of the hanged and the hangmen as a man of good society knows the history of the kings of Europe and their ministers.' When Marie was sixteen, Paris was gripped by a particularly sensational double murderâof Madame La Motte and her son. On 6 May 1777 the perpetrator, Desrues, was executed in the Place de Grève; but what particularly excited public interest was the fact that Desrues was said to be a hermaphroditeâor, as Baron de Grimm put it more elegantly, âBoth the male and female sex would seem unwilling to own him.' This unusual personal background in conjunction with his bravery during his slow and brutal execution endeared Desrues to the crowds, and confirmed his place in criminal folklore. His mortal remains were revered as relics, and his life was commemorated in popular ballads and best-selling pamphlets. He was therefore an obvious subject to take up a prime position in Curtius's

hall of infamy. As Mercier noted, âTo the man in the street Desrues was a more illustrious name than Voltaire.' And it was the men and women in the street whom Curtius was targeting.