Kate Berridge (6 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Among the usual urban congestion of crowds, carriages and street merchants in the immediate vicinity of Marie's home were diversions for all tastes and interests. From the elegantly macabre illusions of Monsieur Pinetti, who by stabbing shadows of birds seemed to make them bleed, to the bloody savagery of the live animal fight, where

bulls with horns cruelly removed were set upon by dogs and wolves, the spectrum of the beautiful and brutal was broad. Two of Curtius's neighbours showed a disregard for the show-business wisdom of not working with children or animals. The theatrical impresario Audinot scored a big hit with his troupe of child actors, and the star turn in Nicolet's troupe was Turcot the tightrope-walking monkey. Other celebrity performers of the show-business fraternity whom Marie and Curtius moved among, and who they could see when they felt like being entertained rather than entertaining, were the girl who danced with eggs tied to her feet and La Petite Tourneuse, billed as a human spinning top. There was also the Incombustible Spaniard, who drank boiling oil and walked barefoot on red-hot iron, and, strengthening national stereotypes, Jacques de Falaise, the eater of live frogs. The ironically named Beauvisage made a reasonable living merely by contorting his ugly pockmarked face into horrible grimaces, while much more stamina went into the acts of the jugglers and high-wire artists, some of whom even dressed up in hot and heavy wild animal costumes to stretch their skills to the limit.

In addition to physical feats, displays of mental agility by every species of savant amazed and delighted in equal measure. Munito the fortune-telling dog and a white rabbit with a talent for algebra enjoyed particular success. The long-eared mathematician was the star turn of a showman whose other attraction raised eyebrows for the wrong reasons. The âpissing puppet', a marionette of a boy in the act of urinating, incited a few killjoys to call for a ban, or at least a Parental Guidance warning. Puppet shows in general were thought dubious family entertainment: âChildren who attend these shows retain all too easily the impressions they receive in these dangerous places. Parents are often astonished to find them informed about things that they should not know about, and they ought to blame the lack of prudence they have shown in permitting their children to be taken to shows that should have been forbidden them.'

Also on offer were clockwork automata and mechanical robots with bronze heads that seemed to speak like humansâpart of a mania for âphilosophical toys' which was in part driven by the rationalist view of man as a machine with a soul. (The topical debate about what it was to be human added to the allure of Curtius's wax doubles.) There was

also every scale of magic-lantern show, ranging from tantalizing views of foreign cities in the pay-per-view portable peep shows to elaborate phantasmagorias that seemed to assume supernatural properties and turn into ectoplasm that threatened to engulf a terrified audience. Just as Curtius modelled the celebrities of the day in wax, for a time a couple of enterprising impresarios enjoyed success on the back of their famous look-alike marionettes. Perhaps the most unusual impersonation was by Turcot the monkey, who, as well as displaying his balancing skills, imitated the leading classical actor of the day. Equally fashionable were the showman scientists, who tended to make monkeys of the people who paid up only to find themselves duped by such fraudulent âphilosophical' and âmechanical' demonstrations as the telepathic and magnetic presentations of Mesmer and Cagliostro.

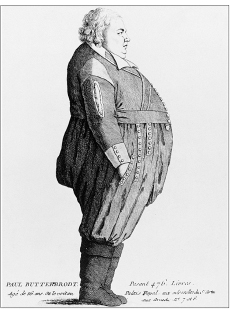

Paul Butterbrodt, the gigantic man employed to publicize the waxworks

Even distinction through ill fortune was turned to profit, although it is debatable how much male sympathy there was for The Virile Boy, a four-year-old of precocious sexual maturity and âbeyond the finest

proportions in the virile organ'. If the crowds were pleased to see him, it was because of his inability to conceal his pleasure in seeing some of themâespecially pretty girls: âIt is especially at the appearance of a woman that his virility manifests itself.' Unusual human forms were almost commonplace on the commercial circuit, and Curtius is said to have employed the vast-girthed Paul Butterbrodt as a barker. Equally intriguing was The Boy Who Could See Underground, who made such an impact that he came to the attention of the academicians, who accredited his talent in learned journals. But if the subterranean talent spot had been taken, this was no problem for the man who won the highest praise for his demonstration of walking on water: âSt Peter himself could not have done better, perhaps with no more grace, nor with more assurance.' These were the sights Marie saw, and the people she moved among.

The Boulevard du Temple was much wider than the maze of dimly lit medieval streets around it, and every inch of space was occupied with the commerce of pleasure. To be seen more easily, street performers erected

tréteaux

, boards raised on trestles by way of simple stages, on which animal-based entertainments offered as much variety as their human competition. The stars of these miniature variety shows were duelling fleas, somersaulting birds and funambulist rats. Marie clearly liked the performing fleas, for she featured a flea circus in her own bill of entertainment at a later stage. Before billposters became more common, live action advertising was popular for theatrical entertainment. In this form of commercial trailer, actors on the theatre balconies that faced the street above the crowds treated passers-by to a taste of the fun they could have if they went directly to the ticket office. But by far the best description of the scope of the fun to be had on Marie's doorstep is that of a contemporary eyewitness: âThere are chairs set up for those who want to watch and for those who want to be watchedâcafés fitted up with an orchestra and French and Italian singers; pastry cooks, restaurant-keepers, marionettes, acrobats, giants, dwarfs, ferocious beasts, sea monsters, wax figures, automatons, ventriloquists and the surprising and enjoyable show of the wise physicist and mathematician Comus.'

The neighbourhood was thronged with peddlers, ticket touts, conjurers and conmen. There was a constant crush of people as well as

carriages trying to pass through. The pedestrians, like eddies around rocks, would gather in greater numbers as a balladeer suddenly struck up with the last words of a newly executed criminal, and there would be a spontaneous singalong. But the magic of the area was the seemingly inexhaustible supply of new things to see. In this colourful community Marie witnessed daily the art of spin, as the public were persuaded to dip into their pockets and pay up to be amazed, amused or abused by a scam. Although as an adult she cultivated an image that conveyed a refined sensibility and emphasized respectable connections, in reality the tough and edgy street culture where Curtius built up the family business had exposed her from an early age to the harsh realities of life. The Boulevard du Temple was even nicknamed the Boulevard du Crime because the constant crowds made it a pickpocket's paradise.

With Curtius distinguishing himself as a showman of great skill, she also learned the art of keeping one step ahead, of anticipating and sustaining public interest. She learned not just how to survive but how to thrive in a fiercely competitive business. In fact Curtius seems to have cornered the market in waxworks, though there is the odd mention of anatomical waxes doing the rounds, and of a tawdry fairground-style wax figure called La Belle Zuleima. Presented as a mummified woman, like a grotesque sleeping beauty, she had very long hair which punters could lift up to inspect her lower body. But these presented not even a hint of a threat to Curtius and his wax wizardry. By contrast the rivalry between Nicolet and Audinot was especially fierce. âOne better at Nicolet's' was the latter's publicity slogan, and it looked as if he had triumphed in one-upmanship when Louis XVI granted the royal seal of approval by allowing him to rename his troupe Les Grands Danseurs et Sauteurs du Roi.

In the emerging collective culture of recreation, commercial entertainment in many new guises was proving to be a unifying force among people who were radically divided by almost every other aspect of their lifestyles. The waxworks were a particularly compelling form of escapism, unlike anything else on offer. While the desire for escapism was equally strong among aristocrats in their mansions and artisans in their attics, the motivations were completely different. For the rich it was to alleviate a stultifying ennui that they

sought stimulation. This even extended to Marie Antoinette, who in a letter to a friend in 1776 confessed, âI am afraid of being bored and I am afraid of myself. To escape this obsession I need movement and noise.' At court, a mannered world-weariness became almost part of the protocol, as Madame de La Tour du Pin described:

It was fashionable to complain of everything; one was bored, one was weary of attendance at court. The officers of the Garde du Corps, who were lodged in the chateau when on duty, bemoaned having to wear uniform all day. The Ladies of the Household in attendance could not bear to miss going two or three times to Paris for supper during the eight days of their attendance at Versailles. It was the height of style to complain of duties at court, profiting from them nonetheless and sometimes indeed often abusing the privileges they carried.

For the poor, escapism was a more urgent respite from an oppressive daily routine. Part of the appeal of the macabre and mysterious, bawdy and amusing, clever and incredible entertainments was as a release from very real hardships. Even before the horrors of the Revolution, Marie experienced that life was cheap. One of the more pernicious privileges of the wealthy was their freedom to hit and run. It was common practice for the carriages of the aristocrats to mow down pedestrians without stopping, causing serious injury and sometimes instant death. Visitors to Paris were horrified by this daily hazard, and Gouverneur Morris was shocked that the wealthy passengers permitted their coachmen to stop only if they thought their horses had been injured. Morris expressed this in a poem sent in a letter to a friend;

Had I supposed a horse lay there,

I would have taken better care.

But by St Jacques declare I can,

I thought 'twas nothing but a man.

The Paris where Marie grew up was also, in the words of a Russian visitor, âjust a whit cleaner than a pigsty'. Beneath a veneer of civilization the city was a mass of mud. In streets without pavements pedestrians had to pick a path around all manner of muckâanimal, vegetableâand humanâas a shocked Mrs Thrale noted: âThe women sit down in the streets as composedly as if they were in a convenient house with the doors shut.' Rain would turn this waste into noxious

molten channels. A common street cry was â

Passez! Payez!

' as, for a small fee, young boys would lay down planks for passers-by. Street valets similarly made a living with a form of on-the-spot dry-cleaning service so that people could still appear presentable. They would whiten stockings with a coating of flour, and blacken shoes with a mixture of oil and soot. The streets also stank of the animal and human ordureâhence the development of scent and a burgeoning consumer market for pleasant smells: the

parfum

for which Paris remains famous originated as air freshener.

One of the most precious commodities was water. Only a third of houses had their own wells, and migrants from the Auvergne carted large barrels through the streets from which they sold water for a few sous a pail. They did a brisk trade, as public fountains were often dry. In a city where daily newspapers were in limited supply, and literacy by no means commonplace, the water carriers also acted as a valued news service, taking the latest gossip from one district to another. With tallow factories, tanneries and slaughterhouses all sluicing out their waste into the Seine, cleanliness was ambitious, and spotting a vast gap in the market the Perrier brothers, before they started bottling water, pioneered water supply for domestic premises. Familiarity with filth gave rise to popular beliefs that it was actually beneficial, and it was widely thought that a thick crust of dirt on a baby's head would promote growth. Similarly, it was widely believed that bodily contact with water was harmful for health and weakened the internal organs, so bathing was not common practice. While Parisians prided themselves on keeping up appearances by wearing the requisite fashionable details such as lace ruffles and going to great trouble to style their hair, the reality was that under both the second-hand wigs of the poor and the society ladies' more elaborate horsehair padded wigs were itching weals on unwashed scalps. On closer inspection lace ruffles revealed a thin dusting of white powder to hide dirt, for as Mercier said, âCleanliness no one expects, but it is only decent to seem well to do.' The skewed priorities were such that a Parisian visited a hairdresser every day, but put on clean clothes only once a month.

As an entertainment district, the Boulevard du Temple was permanently thronged. Marie only had to step outside to be plunged into a mêlée of people selling a vast range of goods and services,

encompassing domestic needs and practical amenities, besides the purely recreational diversions. Given the restrictions on print for public display, street cries were still the most common form of advertising. The soundtrack of Marie's life then was a perpetual chorus of public announcements and invitations to buy, from the simple âPortugal! Portugal!' of the orange-sellers to the barkers with their exaggerated claims for assorted entertainments. There were also the shouts of the oyster-sellers, or

écaillers

âthe hot-dog vendors of the dayâwho could bisect the bivalves in seconds with an expert flourish of a knife and who sold sugared barley water in the months when oysters were not in season. Also part of the urban cacophony was the ubiquitous hurdy-gurdy.