Killing Jesus: A History (4 page)

Read Killing Jesus: A History Online

Authors: Bill O'Reilly,Martin Dugard

Tags: #Religion, #History, #General

The Liberators are in the minority—just sixty men among nine hundred—and if they lose their nerve, there is every chance they will be imprisoned, executed, or exiled. Caesar is known to be a benevolent man, but he is also quick to exact revenge, such as the time he ordered the crucifixion of a band of pirates who had kidnapped him. “Benevolent” in that instance meant executioners dragging the razor-like steel of a

pugio

across each pirate’s windpipe before nailing him to the cross, so that his death might be quicker.

Some of the senators, such as general and statesman Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, have fought in battle and are well acquainted with the act of killing. Brutus, as he is known, was the one sent to Caesar’s home to lure him to the Senate when it appeared he might not show up this morning. It was Caesar who named Brutus to the position of praetor, or magistrate. But Brutus’s family has a long tradition of rejecting tyrants, beginning in 509

B.C.

with Junius Brutus, the man credited with overthrowing Tarquinius Superbus and ending the Roman monarchy. That act of rebellion was as cold-blooded as the murder the Liberators have planned for Caesar.

Other senators, such as the heavy-drinking Lucius Tillius Cimber and his ally Publius Servilius Casca Longus, have the soft and uncallused hands of elected officials. Wielding a killing blade will be a new sensation for them.

Murdering Caesar is the boldest—and most dangerous—of ideas. He is not like other men. In fact, he has become the greatest living symbol of Roman power and aggression. Caesar has so completely consolidated his hold on Roman politics that the only likely outcome of this murder will be anarchy, and perhaps even the end of the Roman Republic.

* * *

This is hardly the first time someone has wanted Julius Caesar dead. The one million inhabitants of the city of Rome are reactive and unpredictable. Caesar is known by everyone and admired by most. Since the age of fifteen, when his father suddenly died while putting on his shoes one morning, Caesar has endured one challenge after another in order to make himself a success. But each contest has made him stronger, and with each hard-won triumph his legend—and his power—has grown.

But in terms of sheer glory, legend, and impact, no moment will ever match the morning of January 10, 49

B.C.

Caesar is a great general now, a fifty-year-old man who has spent much of the last decade in Gaul, conquering the local tribes and getting very rich in the process. It is dusk. He stands on the north side of a swollen, half-frozen river known as the Rubicon. Behind him stand the four thousand heavily armed soldiers of the Legio XIII Gemina, a battle-hardened group that has served under him for the last nine years. Rome is 260 miles due south. The Rubicon is the dividing line between Cisalpine Gaul and Italy—or, more germane to Caesar’s current situation, between freedom and treason.

The population of Gaul has been devastated by Caesar’s wars. Of the four million people who inhabited the region stretching from the Alps to the Atlantic, one million have been killed in battle and another million taken into slavery. After capturing Uxellodunum, a town along the Dordogne River near modern-day Vayrac, Caesar cut off the hands of every man who’d fought against him. And during his epic siege of Alesia, in the hills near what is now called Dijon, he surrounded the fortress with sixty thousand men and nine miles of fierce fortifications. All this could be viewed from above, from tall towers erected by Caesar’s engineers, allowing the Roman archers to rain arrows down on the enemy forces. In order to break out of the besieged town, the trapped Gauls would have to find a way through this killing zone.

When food began running out, the Gauls, under the legendary general Vercingetorix, allowed their women and children to exit the city so that the Romans might feed them. This was an act of dubious kindness, for it likely meant a life of slavery, but it was better than letting them starve to death inside the city. However, Caesar would not allow these innocents to cross over into the Roman lines. As their husbands and fathers looked on from within the city walls, unable to invite them back inside for lack of food, the women and children remained stuck in the no-man’s-land between armies, where they lived on grass and dew until they slowly perished from starvation and thirst. Adding insult, Caesar refused to allow their bodies to be collected for burial.

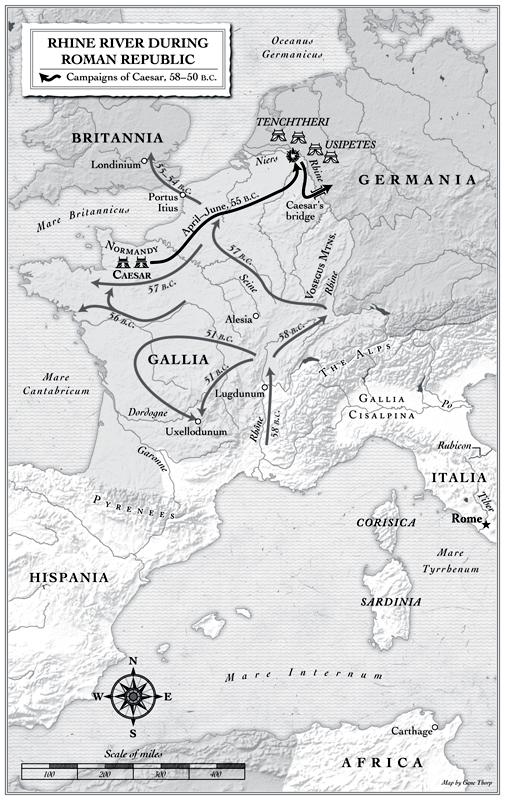

But Caesar’s greatest atrocity—and the one for which his enemies in the Roman Senate have now demanded that he stand trial as a war criminal—was committed against the Germanic Usipetes and Tenchtheri tribes in 55

B.C.

These hostile invaders had slowly begun moving across the Rhine River into Gaul, and it was believed that they would soon turn their attentions south, toward Italy. From April to June of 55

B.C.

, Caesar’s army traveled from its winter base in Normandy to where marauding elements of the Germanic tribes were aligning themselves with Gauls against Rome. These “tribes” were not small nomadic communities but an invading force with a population half the size of Rome’s, numbering almost five hundred thousand soldiers, women, children, and camp followers.

Hearing of Caesar’s approach, the Germans sent forth ambassadors to broker a peace treaty. Caesar refused, telling them to turn around and go back across the Rhine. The Germans pretended to go along with Caesar’s demands, but a few days later they reneged on their word and launched a surprise attack. As Caesar’s cavalry watered their horses along what is now the Niers River, eight hundred German horsemen galloped directly toward them, with intent to kill. The German tactics were peculiar—and terrifying. Rather than wage battle atop their mounts, they leapt from their horses and used their short spears or battle swords to slit open the bellies of the Roman steeds, killing the animals, and sending the now foot-bound legions fleeing in panic.

Caesar considered the attack an act of duplicity because it came during a time of truce. “After having sued for peace by way of stratagem and treachery,” he would later write, “they had made war without provocation.” In a dramatic show of force, Caesar launched a counterattack of his own. Placing his disgraced cavalry at the rear of his force, he ordered the legions to trot double-time the eight miles to the German camp. This time it was the Romans who had the element of surprise. Those Germans who stood their ground were slaughtered, while those who tried to run were hunted down by the disgraced Roman cavalry, who were bent on proving their worth once more. Some Germans made it as far as the Rhine but then drowned while trying to swim the hundreds of yards to the other side.

But Caesar didn’t stop there. His men rounded up all remaining members of the German tribes and butchered them—old men and women, wives, teenagers, children, and toddlers—yielding a killing ratio of eight Germans for each legionary. Generally, the Roman soldiers are educated men. They can recite poetry and enjoy a good witticism. Many have wives and children of their own and could never imagine such barbarous cruelty being visited on those they love. But they are legionaries, trained and disciplined to do as they are told. So they used the steel of their blades and the sharpened tips of their spears to pierce body after body after body, ignoring the screams of terrified children and the wails and pleas for mercy.

Caesar’s revenge began as an act of war but soon turned into a genocide that killed an estimated 430,000 people. And just to show the Germans living on the other side of the Rhine that his armies could go anywhere and do anything, Caesar ordered his engineers to build a bridge across that previously impregnable river. This they accomplished in just ten short days. Caesar then crossed the Rhine and launched a brief series of attacks, then withdrew and destroyed the bridge.

Rome is a vicious republic and gives no quarter to its enemies. But these brutal offenses were too much, even for the heartless Roman leadership in the Senate, who called for Caesar’s arrest. Cato, a statesman renowned not just for his oratory but also for his long-running feud with Caesar, suggested the general be executed and his head given on a spike to the defeated Germans. The charges against Caesar were certainly not without merit. But they stemmed as much from political rivalry as from the slaughter on the banks of the Rhine. One thing, however, is clear: Caesar’s enemies wanted him dead.

* * *

In 49

B.C.

, nearly six years after that massacre, Gaul is completely conquered. It is time for Caesar to return home, where he will finally stand trial for his actions. He’s been ordered to dismiss his army before setting foot into Italy.

This is Roman law. All returning generals are required to disband their troops before crossing the boundary of their province, in this case the Rubicon River. This signals that they are returning home in peace rather than in the hopes of attempting a coup d’état. Failure to disband the troops is considered an act of war.

But Caesar prefers war. He decides to cross the Rubicon on his own terms. Julius Caesar is fifty years old and in the prime of his life. He has spent the entire day of January 10 delaying this moment, because if he fails, he will not live to see the day six months hence when he will turn fifty-one. While his troops play dice, sharpen their weapons, and otherwise try to stay warm under a pale winter sun, Caesar takes a leisurely bath and drinks a glass of wine. These are the actions of a man who knows he may not enjoy such creature comforts for some time to come. They are also the behavior of man delaying the inevitable.

But Caesar has good reason to hesitate. Pompey the Great, his former ally, brother-in-law, and builder of Rome’s largest theater, is waiting in Rome. The Senate has entrusted the future of the Republic to Pompey and ordered him to stop Caesar at all costs. Julius Caesar, in effect, is about to begin a civil war. This is as much about Caesar and Pompey as it is about Caesar and Rome. To the winner goes control of the Roman Republic. To the loser, a certain death.

Caesar surveys his troops. The men of Legio XIII stand in loose formation, awaiting his signal. Each carries almost seventy pounds of gear on his back, from bedroll to cooking pot to three days’ supply of grain. On this cold winter evening, they wear leather boots and leggings and cloaks over their shoulders to keep out the chill. They will travel on foot, wearing bronze helmets and chain mail shirts. All protect themselves with a curved shield made of wood, canvas, and leather, along with two javelins—one lightweight, the other heavier and deadlier. They are also armed with double-edged “Spanish swords,” which hang from scabbards on their thick leather belts, and the requisite

pugiones

. Some men are kitted out with slingshots, while others are designated as archers. Their faces are lined and weathered from years of sun and wind, and many bear the puckered scars from where an enemy spear plunged into their bodies or the long purple scar tissue from the slash of an enemy sword cutting into biceps or shoulder. They are young, mostly between seventeen and twenty-three years of age, but there are some salt-and-pepper beards among them, for any male Roman citizen as old as forty-six can be conscripted into the legions. Young or old, they have endured the rugged physical training that makes the stamina of legionaries legendary. New recruits march for hours wearing a forty-five-pound pack, all the while maintaining complicated formations such as the wedge, hollow square, circle, and

testudo

, or “tortoise.” And all Roman legionaries must learn how to swim, just in case battle forces them to cross a river. Any moment of failure during this rigorous training means the sharp thwack of a superior’s staff across one’s back.

Once a conscript’s four months of basic training are finished, rigorous conditioning and drilling remain part of his daily life. Three marches of more than twenty miles in length while wearing a heavy pack are required from every man each month. When the long miles in formation are done, the legionary’s unit is required to build a fortified camp, complete with earthen ramparts and trenches.

So it is that the tough, loyal, muscled men of Legio XIII are drilled in the art of battle strategy, intuitively able to exploit an enemy’s strengths and weaknesses, and proficient in every weapon of their era. They live off the land, pooling their supplies of grain and any meat they can forage. They have built roads and bridges, delivered mail, collected taxes, served as police, endured the deep winters of Gaul, known the concussive sting of a slingshot-hurled rock bouncing off their helmets, and even played the role of executioner, driving nails through the hands and feet of escaped slaves and deserters from their own ranks who have been captured and condemned to crucifixion. The oldest among them can remember the uprising of 71

B.C.

, when seven thousand slaves, led by a rebel named Spartacus, revolted, were captured, and were crucified in a 240-mile line of crosses that stretched almost all the way from Naples to Rome.

It is Caesar to whom these men have sworn their allegiance. They admire how he leads by example, that he endures the same hardships and deprivations during a campaign that they do. He prefers to walk among the “comrades,” as he calls his troops, rather than ride a horse. Caesar is also well known throughout the ranks for his habit of rewarding loyalty and for his charisma. His men proudly boast of the many women he has had throughout Gaul, Spain, and Britain, and they even make fun of his thinning hair by singing songs about “our bald whoremonger.” Likewise, Caesar gives his legions free rein to chase women and gamble when they are off duty. “My men fight just as well when they are stinking of perfume,” he says.