Killing Jesus: A History (5 page)

Read Killing Jesus: A History Online

Authors: Bill O'Reilly,Martin Dugard

Tags: #Religion, #History, #General

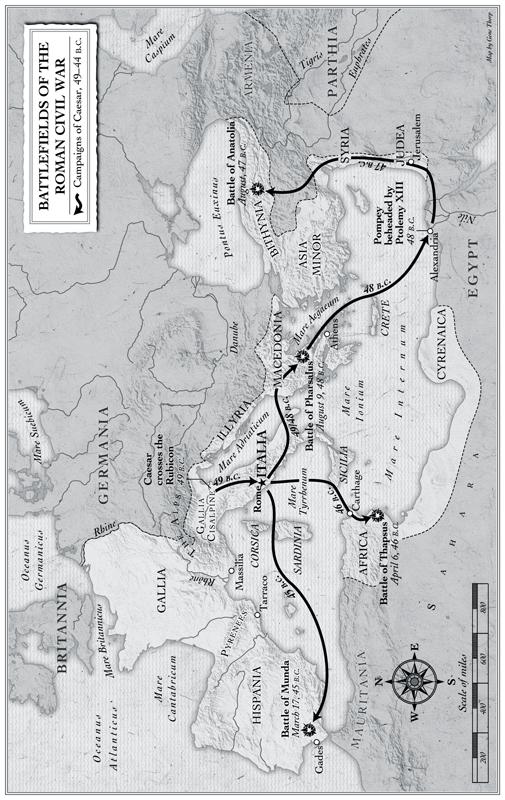

Caesar crossing the Rubicon

But in the end, the legionaries fight, first and foremost, for one another. They have trained together, cooked meals together, slept in the same cramped leather tents, and walked hundreds of miles side by side. No thought is more unbearable than letting down their

commilito

(“fellow soldier”) on the field of battle. They call one another

frater

(“brother”), and the highest honor a legionary can earn is the wreath of oak leaves known as the

corona civica

, awarded to those who risk their lives to save a fallen comrade. That Julius Caesar wears such a crown is testimony to his soldiers that their commander is not a mere figurehead, but a man who can be trusted to wage war with courage and distinction.

But while it is Caesar who will lead the legion into battle, it is his men who will engage the enemy. Theirs is not a compassionate profession, and these are not compassionate men. They are legionaries, tasked with doing the hard, ongoing work of keeping Rome the greatest power in the world.

In the growing darkness, Caesar now addresses his army, reminding them of the significance of crossing from one side of the Rubicon to the other. “We may still draw back,” he tells them, though all within earshot know that the moment for retreat has long since passed. “But once across that little bridge, we shall have to fight it out.”

Legio XIII is not Caesar’s favorite—that would be the Tenth. But, like his other troops, those soldiers are still scattered throughout Gaul. Waiting for them would ruin his plans for a lightning-fast march straight into the heart of Rome.

Julius Caesar may be nervous as the temperature continues to drop and men shiver in the dampness, but any fear is offset by the awareness that each and every soldier in Legio XIII is a killing machine.

Problem is, so are the men they will be fighting. Caesar is about to pit Roman against Roman, legionary against legionary,

frater

against

frater

.

The time has come. Caesar stands alone, gazing over to the other side of the Rubicon. His officers huddle a few feet away, awaiting his orders. Torches light their faces and those of Legio XIII.

“

Alea iacta est

,” Caesar says to no one in particular, quoting a line from the Greek playwright Menander: “The die is cast.”

Caesar and his legion cross into Italy.

* * *

What follows is not just a Roman civil war, but also the first world war in history. The entire Mediterranean rim soon becomes a battleground, its plains and deserts filled with legionaries, its seas brimming with warships conveying these men from one land to another. The fighting is brutal, often hand to hand. The fate awaiting prisoners of war is torture and death, leading many to commit suicide when a battle has been lost rather than submit to the victors. Caesar takes Rome within two months, only to find it abandoned. Merely capturing Rome is not enough. He must have total victory. Pompey has fled, and Caesar gives chase across the Mediterranean, to Egypt.

As he wades ashore to meet with Ptolemy XIII, the teenage king of Egypt, Pompey—the great general, architect, builder, and prodigious lover who was married five times, and who was three times given the privilege of riding in triumph through the streets of Rome after epic battlefield conquests in his youth—is stabbed through the back with a sword, and then stabbed several more times for good measure. Not wanting his murderers to see his expression at the moment death arrives, Pompey pulls the hem of his toga up over his face. His murderers quickly cut off his head, and leave his corpse on the sand to be picked apart by shorebirds. Thinking it will please Julius Caesar, the Egyptians bring him Pompey’s severed skull. But Caesar is devastated. He weeps, and then demands that the rest of the body be retrieved so that it might be given a proper Roman burial.

But Pompey’s murder is not the end of the war, for his outraged allies and sons soon take up his cause. In the end, Caesar will win the civil war and take control of the Roman Republic, much to the joy of its common citizens, who revere him. Yet four years of conflict will pass before that day arrives. In the meantime, Julius Caesar will command his legions in locales ranging from Pharsalus, in central Greece; to Thapsus, in Tunisia; to the plains of Munda, in present-day southern Spain,

1

and his legend will only grow larger.

Caesar’s conquests, however, are not only on the battlefield.

* * *

The year is 48

B.C.

A civil war is taking place in Egypt at the same time as the civil war in Rome. On one side is the twenty-one-year-old Cleopatra. On the other is her thirteen-year-old brother, Ptolemy XIII, who is being advised by a conniving eunuch named Potheinos. Ptolemy has succeeded in driving Cleopatra from her palace in the seaside capital at Alexandria. The troubles in Italy then intervene when Caesar chases Pompey to Alexandria. It is Potheinos, thinking to ally himself with Caesar, who has Pompey beheaded on the Egyptian beach just moments after the Roman is assassinated while coming ashore to align himself strategically with Ptolemy XIII.

But Caesar is disgusted by Potheinos’s barbarous act, for he had planned to be lenient toward Pompey. “What gave him the most pleasure,” the eminent historian Plutarch will one day write of Caesar, “was that he was so often able to save the lives of fellow citizens who had fought against him.”

Caesar moves into Egypt’s royal palace for the time being. But he fears that Potheinos will attempt to assassinate him, so he stays up late most nights, afraid to go to sleep. One such evening, Caesar retires to his quarters. He hears a noise at the door. But rather than Potheinos or some other assassin, a young woman walks into the room alone. It is Cleopatra, though he does not yet know that. She has slipped into the palace through a waterfront entrance and navigated its stone corridors without being noticed. Her hair and face are covered, and her body is wrapped in a thick dark mantle. Beguiled, Caesar waits for this stranger to reveal herself.

Slowly and seductively, Cleopatra shows her face, with her full lips and aquiline nose. She then lets her wrap drop to the marble floor, revealing that she is wearing nothing but a sheer linen robe. Caesar’s dark eyes look her body up and down, for he can now clearly see much more than the outline of Cleopatra’s small breasts and the sway of her hips. The lust between them is not one-sided. In that moment of revealing, one historian will write of Cleopatra, “her desire grew greater than it had been before.”

Cleopatra knows well the power of seduction, and she is about to bestow upon Caesar her most precious gift—intending, of course, to gain a great political reward. The bold gambit pays off immediately. That night, she and Caesar begin one of the most passionate love affairs in history, a political and romantic entanglement that will have long-lasting effects on the entire world. Before the morning sun rises, Caesar decides to place Cleopatra back on the Egyptian throne—just as she had hoped. For Caesar, this means he is now aligned with a woman who owes her reign to the legacy of Alexander the Great, the omnipotent Macedonian conqueror he so admires. The confluence of his growing dynasty and Cleopatra’s is a powerful aphrodisiac. They speak to each other in Greek, although Cleopatra is said to be fluent in as many as nine tongues. Each is disciplined, sharp-witted, and charismatic. Their subjects consider them benevolent and just, and both can hypnotize a crowd with their oratorical skills. Cleopatra and Egypt need Caesar’s military might, while Caesar and Rome need Egypt’s natural resources, particularly her abundant grain crops. It could be said that Caesar and Cleopatra make the perfect couple, were it not for the fact that Julius Caesar is already married.

Cleopatra, paramour of Caesar and, later, Marc Antony

Not that this has stopped Caesar in the past. He has had three wives, one of whom died in childbirth, another whom he divorced for being unfaithful, and now Calpurnia. He sleeps with the wives of friends, often thereby gleaning information about colleagues. The love of his life is Servilia Caepionis, mother of the treacherous Marcus Junius Brutus—whom many believe to be Caesar’s illegitimate son.

But Caesar’s most notorious affair was not with a woman. It is widely rumored that, in his youth, he had a yearlong affair with King Nicomedes IV of Bithynia.

2

The sneering nickname “Queen of Bithynia” still follows Caesar.

Lacking from Caesar’s many dalliances has been an heir. The number of his bastard offspring scattered throughout Gaul and Spain is legendary, but he had only one legitimate child, Julia—who, ironically, married Caesar’s rival Pompey—and she has long since died in childbirth. Calpurnia, Caesar’s current wife, has been unable to give him a child.

Cleopatra gives birth to a son on June 23, 47

B.C.

She names him Philopator Philometor Caesar—or Caesarion for short. A year later, Cleopatra travels to Rome, where she and the child live as a guest of Caesar and Calpurnia’s at Caesar’s Trastevere villa. When Caesar is forced to return to war, Cleopatra and the child remain behind with Calpurnia, who, not surprisingly, despises the Egyptian woman. But Caesar has ordered her to stay in Rome, even as rumors swirl throughout the city about her and Caesar possibly getting married one day. Caesar has not helped matters by having a statue of a naked Cleopatra erected in the Temple of Venus, portraying her as a goddess of love.

For reasons known only to him, Caesar allows Caesarion to use his name but refuses to select him as heir. Instead, his will states that upon his death his nephew Octavian will become his adopted son and legal heir.

Cleopatra is a shrewd and ruthless woman. She knows that she will lose her hold on Egypt should her relationship with Caesar end. She has quietly begun to plot a betrayal—an Egyptian overthrow of Rome. It all depends on Caesarion’s being named Julius Caesar’s rightful heir and successor—and that means somehow getting Caesar to change his will.

Or maybe there is another way: should Caesar be named king of Rome, he will need a queen of royal birth to consummate a true royal marriage. So Cleopatra’s plan is simple: continue pushing Caesar to accept the crown of king of Rome. Then they will marry, and her son will rule as legal heir when Caesar dies.

Everything seems to be going Cleopatra’s way. It’s clear that the Senate is about to name Caesar as king. This will all but ensure their marriage and the removal of Octavian as a threat to Caesarion’s eventual claim to the thrones of both Egypt and Rome.

Caesar, the master statesman, is being outmaneuvered by a woman less than half his age, and with no army at her disposal. Thousands of men have died in Rome’s civil war, all in an attempt to control the Roman Republic. But Cleopatra is on the verge of accomplishing the same feat solely through seduction.

It’s all so brilliant. So perfect. Then, of course, comes the Ides of March. Not only will there not be a Roman Republic by the time the battle for succession comes to an end, but there will no longer be a Caesarion, either.