Killing Kennedy (3 page)

Authors: Bill O'Reilly

But not all those invited to the inauguration have turned up. The famous entertainers attending the previous night’s parties were promised prime seats for this pivotal moment in American history, but owing to the cold and a 100-proof celebration that stretched into the wee small hours, singer Frank Sinatra, actor Peter Lawford, and composer Leonard Bernstein—along with a host of others—opted to sleep late and watch the event on television. “I’ll see the president’s second inaugural” is their common refrain.

But there will be no second inaugural. For John Fitzgerald Kennedy is on a collision course with evil.

* * *

Approximately 4,500 miles away, in the Soviet city of Minsk, an American who did not vote for John F. Kennedy is fed up. Lee Harvey Oswald, a former U.S. Marine Corps sharpshooter, has had enough of life in this Communist nation.

Oswald is a defector. In 1959, at age nineteen, the slightly built, somewhat handsome, enigmatic drifter decided to leave the United States of America, convinced that his socialist beliefs would be embraced in the Soviet Union. But things haven’t gone according to plan. Oswald had hoped to attend Moscow University, even though he never graduated from high school. Instead, the Soviet government shipped him more than four hundred miles west, to Minsk, where he has been toiling in an electronics factory.

Lee Harvey Oswald at his application for Soviet citizenship in 1959.

(Bettmann/Corbis/AP Images)

Oswald is fond of being on the move, but the Soviets have severely restricted his travel. Until now, his life has been chaotic and nomadic. Oswald’s father died before he was born. His mother remarried and soon divorced. Marguerite Oswald had little money and moved young Lee frequently, traveling through Texas, New Orleans, and New York City. By the time he dropped out of high school to enlist in the marines, Oswald had lived at twenty-two different addresses and attended twelve different schools—including a reform institution. There, a court-ordered psychiatric evaluation found him to be withdrawn and socially maladjusted. He was diagnosed as having “a vivid fantasy life, turning around the topics of omnipotence and power, through which he tries to compensate for his present shortcomings and frustrations.”

The Soviet Union in 1961 is hardly the place for a man in search of independence and power. For the first time in his life, Lee Harvey Oswald is stuck. He gets up every morning and trudges to the factory, where he labors hour after hour operating a lathe, surrounded by coworkers whose language he barely understands. His defection in 1959 was reported by American newspapers because it was extremely unusual for a U.S. Marine—even one so pro-Soviet that his fellow marines had nicknamed him “Oswaldskovich”—to violate the Semper Fi (Always Faithful) oath and go over to the enemy. But now he is anonymous, which he finds completely unacceptable. Defection doesn’t seem like such a good idea anymore. Oswald confides to his journal that he is thoroughly disenchanted.

Lee Harvey Oswald has nothing against John Fitzgerald Kennedy. He doesn’t know much about the new president or his policies. And while Oswald was a crack shot in the military, little in his past indicates that he would be a threat to anyone but himself.

As America celebrates Kennedy’s inauguration, the defector writes to the U.S. embassy in Moscow. His note is short and to the point: Lee Harvey Oswald wants to come home.

PART I

Cheating Death

1

A

UGUST 2, 1943

B

LACKETT

S

TRAIT,

S

OLOMON

I

SLANDS

2:00 A.M.

It is February 1961. The new president has a coconut on his desk. He is lucky to be alive, having already cheated death three times in his short life, and the unusual paperweight is a reminder of the first time he came face-to-face with his own mortality. His staff makes sure to place the coconut in a prominent position when they move the new president into the Oval Office. They know their boss wants that very special coconut in his line of sight, because it is a reminder of a now-famous incident that tested his courage.

* * *

Eighteen years earlier, in 1943, on a balmy Pacific night, three American patrol torpedo boats cruise the Blackett Strait in the South Pacific, hunting Japanese warships near a hotly contested area known as The Slot. At eighty feet long, with hulls of two-inch-thick mahogany, and powered by three powerful Packard engines, these patrol torpedo (PT) boats are nimble vessels, capable of flitting in close to sink Japanese battleships with a battery of Mark VIII torpedoes.

The skipper of the boat bearing the number 109, a young second lieutenant, slouches in his cockpit, half alert and half asleep. He has shut down two of his engines to conceal PT-109 from Japanese spotter planes. The third engine idles softly, its deep propeller shaft leaving almost no wake in the iridescent water. He gazes across the ocean on this night without moon or starlight in the hope of locating the two other nearby PTs. But they are invisible in the darkness—just like 109.

The skipper doesn’t see or hear the destroyer

Amagiri

until it’s almost too late. She’s part of the Tokyo Express, a bold Japanese experiment to transport troops and weapons in and out of the tactically vital Solomon Islands via ultrafast warships. The Express relies on speed and the cover of night to complete these missions.

Amagiri

has just dropped nine hundred soldiers at Vila, on nearby Kolombangara Island, and is racing back to the Japanese bastion at Rabaul, New Guinea, before dawn will allow American bombers to find and destroy her. She is longer than a football field but a mere thirty-four feet at the beam, her shape allowing

Amagiri

to knife through the sea at an astonishing forty-four miles per hour.

In the bow of PT-109, Ensign George “Barney” Ross of Highland Park, Illinois, also peers into the night. His previous boat was recently, accidentally, sunk by an American bomber, and he volunteered for this mission as an observer. Now Ross is stunned when, through his binoculars, he sees the

Amagiri

just 250 yards away, bearing down on 109 at full speed. He points into the darkness. The skipper sees the ship and spins the wheel hard, trying to turn his boat toward the rampaging destroyer to fire his torpedoes from point-blank range—either that, or the Americans will be destroyed.

PT-109 can’t turn fast enough.

It takes just a single terrifying instant for

Amagiri

to slice through the mahogany hull. The diagonal incision begins on the right side, barely missing the cockpit. The skipper is almost crushed, at that moment thinking to himself, “This is how it feels to be killed.” Two members of the thirteen-man crew die instantly. Two more are injured as PT-109 explodes and burns. The two nearby American boats, PT-162 and PT-169, know a fatal blast when they see one, and don’t wait around to search for survivors. They gun their engines and race into the night, fearful that other Japanese warships are in the vicinity.

Amagiri

doesn’t stop either, speeding on to Rabaul, even as her crew watches the small American craft burn in her wake.

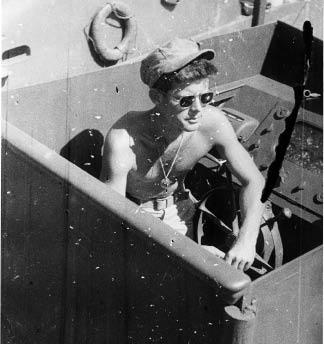

Lieutenant John Fitzgerald Kennedy in the cockpit of PT-109.

(Photographer unknown, Papers of John F. Kennedy, Presidential Papers, President’s Office Files, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston)

The men of PT-109 are on their own.

The skipper, and the man responsible for allowing such an enormous vessel to sneak up on his boat, is Lieutenant John Fitzgerald Kennedy. He is twenty-six, rail thin, and deeply tanned, a Harvard-educated playboy whose father forced him to leave naval intelligence to seek a combat position when it was discovered that his son’s Danish mistress was suspected of being a Nazi spy. Being second-born in a family where great things are expected from the oldest son, Kennedy has had the luxury of a frivolous life. He was a sickly child, grew into a young man fond of books and girls, and, with the exception of commanding a minor vessel such as PT-109, has shown no interest in pursuing a leadership position in politics—an ambition required of his older brother, Joe.

But none of that matters right now. Kennedy must find a way to get his men to safety. Later in life, when asked to describe the night’s imminent turning point, he will shrug it off: “It was involuntary. They sunk my boat.”

His words belie the fact that he might have been court-martialed for allowing his boat to be sunk and two of his men to be killed. But the sinking of PT-109 will be the making of John F. Kennedy—not because of what just happened, but because of what is about to happen next.

The back end of PT-109 is already on its way to the bottom of the Blackett, some 1,200 feet below. The forward section of the hull remains afloat, thanks to watertight compartments. Kennedy gathers the surviving crew members on this section to await help.

Amagiri

’s wake is sweeping the flames away from the wreckage of 109, allaying Kennedy’s fears that the gasoline fires will ignite any remaining ammunition or fuel tanks. But as the hours pass—one, then two and three—and it becomes obvious that help is not coming, Kennedy knows he must devise a new plan. The Blackett Strait is bordered on all sides by small islands that are home to thousands of Japanese soldiers. It’s certain that someone on land has seen the explosion.

“What do you want to do if the Japs come out?” Kennedy asks the crew. Completely responsible for the lives of his men, he is at a loss. The hull is beginning to sink, and the only weapons he and his men possess are a single machine gun and seven handguns. A firefight would be ludicrous.

The men can plainly see a Japanese camp less than a mile away, on Gizo Island, and know that two other large bases exist on Kolombangara and Vella Lavella islands, each just five miles away.

“Anything you say, Mr. Kennedy. You’re the boss,” replies one crewman.

But Kennedy is not comfortable being the boss. In his months being skipper of the 109, his job has largely consisted of steering the boat. The men complain that he is more interested in chasing girls than commanding a ship. Kennedy is much more at ease in a supporting role. Growing up, he took orders from his domineering father and looked up to his charismatic older brother. His dad, Joseph P. Kennedy, is one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in America, and a former ambassador to Great Britain. His brother Joe, at twenty-eight years old, is a flamboyant naval aviator soon to see action flying antisubmarine missions against the Nazis in Europe.

The Kennedy family takes all its directives from their patriarch. John Kennedy will one day liken the relationship to that of puppets and their puppet master. Joseph P. Kennedy decides how his children will spend their lives, monitors their every action, attempts to sleep with his sons’ and daughters’ girlfriends, and even had one of his own daughters lobotomized. He has already pinpointed Joe as the family politician. Indeed, his father saw to it that his eldest was a delegate at the 1940 Democratic National Convention. Meanwhile, in those days before the war broke out, John spent his time writing and traveling. Many in the family still believe that writing might become his chosen profession.