Kissing Kin

Authors: Elswyth Thane

ELSWYTH THANE

To

Harold A. Foster

- Title Page

- Dedication

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- THE SHOW GOES ON

- 1.

Spring in Williamsburg 1917 - 2.

Christmas at Farthingale 1917 - 3.

Summer in Gloucestershire 1918 - 4.

Autumn on the Somme 1918 - 5.

Christmas at Farthingale 1918 - INTERMISSION

- 1.

Spring in Williamsburg 1922 - 2.

Summer in Cannes 1922 - 3.

Autumn in Salzburg 1925 - THE LIGHTS ARE DIMMING

- 1.

Autumn in Cannes 1930 - 2.

Summer in Salzburg 1934 - About this Book

- Other titles in the series

- Copyright

T

HE HUMAN MEMORY

is a tricky and unreliable thing, and the research for the background of this book, which lies within the experience of a great many people today, has therefore been as carefully done as for remote historical times. The English illustrated periodicals are the last word in accuracy and vivid coverage on the 1914–1918 war, and on current opinion during the growth of Nazism. I am grateful to Air Marshal Sir William Welsh, Air-Commodore Peregrine Fellowes and Mr. Francis Vivian Drake, who flew with the R.A.F. during the First World War, for helpful comment and additional

information

on the pages concerned with early combat flying, which was so different from the work done by the Flying Fortresses and Spitfires in the recent past.

The summers in England which were an unalterable part of my life from 1928 to 1939 supply me with a certain personal viewpoint, but the opinions expressed by Johnny Malone and Bracken Murray in the book are drawn from the published record of foreign correspondents and statesmen in Europe during those years. No balanced estimate of the twenty-five years between the wars can be complete without a thoughtful study of Leopold Schwartzschild’s

World

In

Trance

—a book which should be compulsory reading for every adult in the Western World.

Miss Barbara Hayes of the British Information Service very kindly made it possible for me to learn more about St.

Dunstan

’s than is readily available in America. Dr. Joseph Fobes gave patient and comprehensible answers to my queries about surgical details. And as always, Mrs. F. G. King and the staff of the New York Society Library have been endlessly helpful to me.

E. T.

1948

T

HE

TWINS

DESCENDED

from the train in silence, looking exactly alike in their young tautness and gravity, though there was nothing feminine about the set of Calvert’s slender shoulders, and Camilla’s fine-drawn face and colt-like frame were anything but tomboy. They had no luggage.

Still silent, they set out along the familiar arching green street which led to what, since Great-grandfather Ransom’s death a few years before, had become known in the family as Aunt Sue’s house, on the other side of town. By unspoken consent they avoided England Street, where the Sprague cousins lived. It was no day for family junkets and frivolity. They had run away from Richmond, to come here—sneaked out, in fact, by a series of fibs and childish manoeuvres designed to deceive their trustful mother. They felt like rats, and they held their heads high.

The subtle psychological bond which exists between twins from birth and reduces the necessity of speech between them to a minimum amounting to thought transference, supported them as they went. Almost without discussion, certainly

without

argument, their decision had been taken the night before in Camilla’s room, after their mother had gone to bed. Aunt

Sue was the one to ask. Aunt Sue always knew what you should do, and what you must not do. Quietly and without any fuss or foolish questions, Aunt Sue would help them to sort themselves out and settle this thing which rode them. To Aunt Sue they had fled, empty-handed and luncheonless, as all the family were accustomed to do every so often, to say, “And so I thought—” and “Of course

you

can see—” and “

Don’t

you agree—?”

She always told them, without nonsense. And she always saw, even if she didn’t always agree. And in the end you were comforted and sustained, even if you had been wrong.

So they came to the gate in the white picket fence, with its chain and cannon-ball weight, and creaked through it, and marched up the path between low box hedges, their chins well up. Old black Uncle Micah, Aunt Sue’s butler, opened the door to them with exclamations of astonishment and joy, and escorted them to the dining-room where Aunt Sue was just finishing luncheon.

“

Well!

” she said, and rose, and kissed them both soundly, Camilla first because she was the girl, but Calvert loudest because he was the boy. And then she said, “Have you had anything to eat?” and when they shook their heads a look passed between her and Uncle Micah and he bustled away kitchenwards.

Hagar, who was Uncle Micah’s youngest, at once appeared to lay two places for them with gleaming silver and old flowered china, and Uncle Micah bustled back with food as hot and lavish as if they had been prompt and bidden guests. They ate hungrily, and Aunt Sue had another cup of coffee to keep them company. Meanwhile they assured her that everyone in Richmond was well, and agreed that the weather was very warm for March. They said how sweet Williamsburg always looked in the spring, and how forward the gardens were

everywhere

. They heard all the latest news from the Princeton cousins, who had done nothing notable, and from the London cousins, who were being bombed from the air by both

Zeppelins and aeroplanes now, and from Cousin Phoebe, who was a nurse in France, and Cousin Bracken, who was a war correspondent.

And then Aunt Sue said, “Have you had enough to eat?” and they nodded above empty plates. She pushed back her chair and said, “Then come into the drawing-room and tell me about it.”

They followed her, wordlessly linked in their twinship, linked too by their rather clammy, nervous hands which met and clung as they passed through the door behind her. She sat down on the sofa and they stood beside her, right hand in left hand, wondering how to begin, looking exactly alike….

She cut the ground from under them briskly.

“I suppose you’ve got some idea you want to go and fight this war,” she said, and they both spoke at once, overflowing with gratitude.

“Cousin Phoebe is already there, and—”

“Cousin Bracken’s Sunday article in the

Star

said—”

“I thought so,” said Sue. “And your mother thinks you’re too young, is that it?”

“We’re twenty-three,” they pointed out resentfully, with one voice. And Calvert added, “We’re the eldest. Eliot comes next, and he’s only seventeen.” (Eliot was one of the Princeton bunch.)

“And besides, Eliot would never get into the Army on account of his eyes,” said Camilla, with a prideful glance at that perfect specimen, her brother, who didn’t have to wear spectacles.

“I see,” said Sue serenely. “Well, what do you have in mind to do about it?”

“I could be a nurse like Cousin Phoebe,” said Camilla.

“I just want to kill Germans,” said Calvert unemphatically. “I don’t want to write about this war, like Cousin Bracken. I’m younger than he is, anyway. I just want to take the quickest and easiest way to get a gun and shoot me some Germans.”

“There isn’t any short cut to that, I’m afraid,” said Sue, who

could remember Manassas and San Juan Hill. “And nursing wounded men isn’t very picturesque, you know, Camilla, except perhaps the uniform.”

“Oh, I realize that,” said Camilla quickly. “I know Cousin Phoebe’s letters almost by heart, the ones she wrote last year from that hospital near Nieuport. But the sight of blood doesn’t make me sick, and I always take care of Calvert when he’s ill, and I don’t need much sleep to get along, and I’m much stronger than I look, and lots younger than Cousin Phoebe.”

“Mmmm,” said Sue thoughtfully, her gaze resting on a big jar of blue iris which stood against the light.

“So we thought—” Calvert began anxiously, and

simultaneously

Camilla said, “So if you’d only—” and they looked at each other and then at her and waited. But she was silent so long, not seeming to be aware of their presence any more, that they went and sat down one on either side of her and each took a hand. “Honey, what are you thinking?” Camilla asked softly.

“I was thinking how familiar it all sounds,” Sue said, not looking at either of them. “And how it keeps on happening to us, time after time. I was thinking about when Eden went to Richmond and scandalized everybody there by being kind to the wounded Yankees in Libby Prison. That was before your mother was born—even before your Grandmother Charlotte married my brother Dabney. And I was thinking of when they all went off to Cuba—your Cousin Fitz and Gwen had been married only a week, but she never tried to hold him back. And I was remembering how when this war started we all hoped it wouldn’t come here—though Bracken always said we’d be in it before the end came. I remember thinking, back in 1914, They’re all too young for this one—they were all born too late—except Calvert.” Her hand tightened on his. “You see, I’ve known all along that Calvert would want to go.”

“Ever since the

Lusitania

,” said Calvert. “But mother—”

“I know,” said Sue gently. “But it’s hard for her, Calvert, with your father dead. You and Camilla are all she’s got. You must be patient.”

“We have been patient,” Calvert pointed out. “It’s nearly two years since the

Lusitania

, and how far have we got? Wilson has broken off diplomatic relations! Not declared war on Germany, mind you, nothing so impulsive as that! Just handed the German Ambassador his passports with a tactful slap on the wrist! ‘Armed neutrality,’ what good is that? I for one am not going to sit around any longer, I’m going up to Canada and enlist! I’m of age, and no one can stop me; It’s done every day, the whole Canadian Army is stiff with Americans!”

“I don’t blame you for feeling that way,” Sue said fairly. “I’ve heard other people talk the same way, right here in Williamsburg. But as for Camilla—”

“Oh, please, Aunt Sue, I can’t stay here and do nothing if Calvert is in it, I’d go crazy! And besides—what about Aunt Eden in the old days? And look at Cousin Phoebe now—and Cousin Virginia too, in London!”

“Their men are in it, Camilla. Virginia married an

Englishman

, and Phoebe—well, Phoebe is in love with one. It’s different for them, and besides, they’re older.”

“Well, so shall I have a man in it!” cried Camilla fiercely. “My own brother, you can’t ask for better than that! We’re

twins!

We always do things

together.

I can’t stay home and let Calvert take all the risks and discomforts, I’ve got to do my share! Else when he got back he’d know a lot of things I didn’t, and I’d be

ashamed!

And if he got killed—and I’d sat safe at home—I’d

despise

myself for ever!”

“I see,” said Sue unargumentatively, and they waited,

watching

her. “And what about your music?” she asked then, for Camilla’s singing voice had great promise and had been

carefully

trained, though family opinion was dead against her using it professionally.

“It will have to wait, like a lot of other things, till the war is over,” said Camilla. “Nobody in Europe can stop to study singing now, why should I?”

“I see,” Sue said again, and Camilla added in a sort of

mutter, “If I had my way I’d cut my hair and go as a boy, the way Grandmother Tibby did before Yorktown!”

“Yes, but have you laid any other plans?” Sue inquired reasonably, and Camilla grinned, and Calvert laughed and said, “We thought Dinah would be the most help, to Camilla, at least, if we could get to her.”

“If you could talk Mother round for us, that is,” said Camilla. “Calvert doesn’t care if he gets a commission or not, so long as he gets

in,

and soon. And I don’t care what I do so long as I do

something

, right away. So we thought if we went up to New York and asked Dinah about getting a passage to England—’

“No doubt they could make use of you as a VAD at her sister’s hospital down in Gloucestershire,” said Sue.

“Or the house in London where Virginia is,” said Camilla, for the idea of a country mansion turned into a hospital seemed tame if one could be in London where the bombs came down.

“Well, we could ask,” said Sue.

“And what about Mother?”

“I’ll talk to her. You telegraph her and stay here to-night, and we’ll write to Dinah so she’ll be prepared. And tomorrow I’ll go back to Richmond with you and have a talk with your mother.”

They kissed her, one on either side.

“You’re wonderful,” they said, and her smile was a little rueful.

They spent the evening concocting the letter to Dinah in New York.

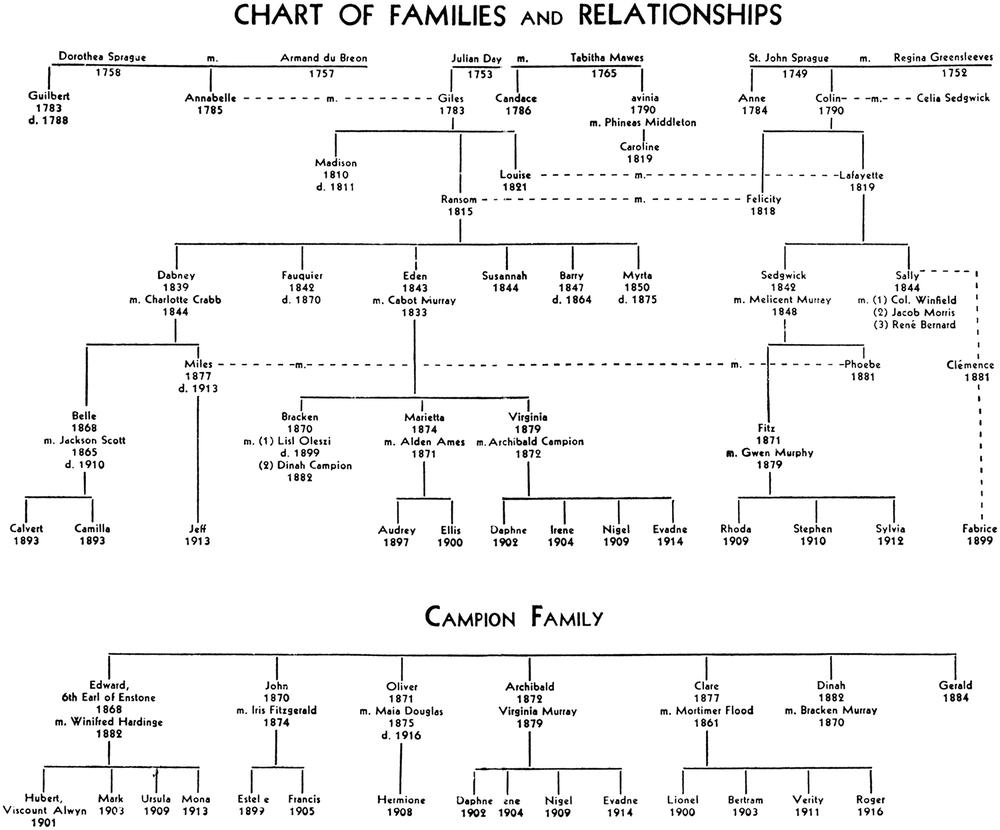

English Dinah was the sister of Edward, Earl of Enstone, and had married their Cousin Bracken Murray and come to live in New York where he owned and edited a newspaper. Bracken’s sister Virginia had married another of Dinah’s brothers, one who wasn’t an earl, only a lawyer in the Inner Temple—a KC with a wig and a black gown and a single eyeglass. The cousins at home in Williamsburg and Richmond had never seen Virginia’s Archie, but they all loved Bracken’s

Dinah, who always came to the family Christmases and

birthdays

and belonged to them from the first. Dinah was born a ladyship, but gave herself no airs, and was little and

reddish-haired

and wonderfully dressed and so in love with Bracken it made your throat ache to see them together.

They had been in England on their yearly visit to Cousin Virginia, Camilla recalled as she sat at Sue’s desk writing down the letter to Dinah more or less at everybody’s dictation, after dinner that evening—Dinah and Bracken had been in England when the war began, and because she had been delicate ever since losing her only baby Dinah had broken down completely under the strain of nursing wounded men

during that first terrible winter in London when the Earl’s house in St. James’s Square had been turned into a hospital for officers and all the family wives had gone to work there as VADs. So Bracken brought her back to New York and she was recuperating there when Cousin Phoebe suddenly decided to go to Europe in the spring of 1915—which was convenient because Phoebe had been able to leave little Jeff in Dinah’s empty nursery….

Camilla looked up suddenly from the letter, interrupting a well-rounded sentence of Calvert’s about his necessity to go and shoot Germans. “Aunt Sue, what was that you said about Cousin Phoebe being in love with an Englishman?”

“Oh, dear,” said Sue. “Well, you may as well know, if you’re going over there.”

“I thought she went abroad because a friend of hers who was married to a German prince hadn’t been heard from after the war began,” said Calvert.

“She did. But Rosalind is safe in England now—they got her out of Germany through Switzerland.”

“I thought it was funny Cousin Phoebe didn’t come back,” said Camilla. “Who is it she’s in love with? And why doesn’t she marry him?”

“He’s an officer in the British Army. And he had a wife.”

“Aha!” said Calvert, not pleased.

“Now—you may as well both get this thing about Phoebe

straight once and for all,” said Sue earnestly. “Ordinarily it might not have come up. But you’ll have to know all about it now, though your mother might think I was wrong to tell you. Phoebe fell in love with Oliver Campion in London years ago—the summer Edward VII was crowned. They didn’t mean to—they were both engaged to somebody else before they met each other.”

“

Well!

” said Camilla, sitting up. “It sounds like something in one of Cousin Phoebe’s books. Tell us more.”

“It wasn’t funny, Camilla,” Sue said quietly, and Camilla laid down her pen and came to sit beside her on the sofa. “Oliver was just as much in love with Phoebe, but they both tried desperately hard to do what they thought was right,” Sue went on. “They decided they must get along without each other, as though they had never met. Oliver married Maia, as he was supposed to do, and went out to India with the

regiment

. And Phoebe finally married your Uncle Miles and settled down here in Williamsburg.”

“I remember the night they announced it,” said Camilla. “At a Christmas party at Cousin Sedgwick’s. I thought that night she was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen, and I never could understand why she married Uncle Miles. She could have had anybody in the world, I always thought. She was rich and famous for her books and still young, and—and so sophisticated—and poor Uncle Miles always seemed so

dull,

for her to marry!”