L.A. Noire: The Collected Stories (5 page)

Read L.A. Noire: The Collected Stories Online

Authors: Jonathan Santlofer

Tags: #Fiction, #Crime, #Mystery & Detective, #General, #Short Stories (Single Author)

Or to keep us from taking it away from him.

We didn’t see Millie right away, but we checked out the rest of the house, and she was in the bedroom. She was sprawled on the floor next to the bed, blood all over, and her head at an odd angle. Lew knelt down next to her, tried for a pulse, put his lips to her mouth, shook his head.

“Oh, you poor baby,” he said. “You were dying by inches and now you’re gone for real. Ah, Millie, you couldn’t listen, could you? You just couldn’t, poor baby. By God, you deserved better than what you got.”

He stood up and looked surprised to see me there. Like for a minute there it was just the two of them, and him talking to her, and no one else in their world.

To me he said, “Well, we got the fucker now, Charlie. We get to slam the barn door on him now that the horse is miles away and gone forever. If they don’t give him the gas, he’ll spend the rest of his life in a cell. The one good thing that comes out of all this is the world’s through with him.”

We were talking about that, and speculating about his chances of winding up in the gas chamber, and what difference it made one way or the other, and then there was a sound from where she was lying, and we stopped talking and turned to look at her.

And she opened her eyes. She said, “Lew?”

Her eyes closed.

And opened again. “Where’s Joe? Is Joe okay?”

Her voice was very faint, her eyes unfocused. Lew drew a breath, let it out. “Jesus,” he said. It was somewhere between a curse and a prayer. Then he said, “Charlie, go get on the phone. Call in, get an ambulance out here on the double. Go!”

So I went back to the other room, where Joe was passed out in the chair where Lew had put him. I didn’t have a number for a hospital, so I called the operator and gave her the address and told her to arrange for an ambulance.

In the bedroom, Millie looked as though she’d been crying. Tears down her cheeks, along with the blood and all. I told Lew I’d made the call, and he lowered his voice and said he didn’t know if she would make it. “She goes in and out,” he said. “You’d better wait outside so they’ll get the right house. Flag ‘em down before they fly right on by.”

I was on my way, but I stopped in the front room to look at the husband. He’d slipped off the chair and was sitting on the floor with his head on the chair cushion. I thought to myself that this piece of garbage was one lucky son of a bitch. He was sitting on a one-way ticket to Q, and then she opened her eyes and set him free.

Free to do it all over again.

The front door was open, and I’d hear the siren in plenty of time, so I stayed where I was. And I sort of heard something from the bedroom, or half heard it, and while I was trying to figure out just what it was, I heard the siren of an ambulance maybe three, four blocks away.

So I went outside and stood on the front step, and I motioned to the ambulance and pointed out where they could park, and then Lew was beside me, hanging his head.

“I think she’s gone,” he said.

Joe went to prison. There was no trial, his court-appointed lawyer had him plead it out, and that way he beat the gas chamber. The sentence was twenty to life, and Lew said that wasn’t long enough, and swore he’d turn up at the guy’s parole hearing and make sure he didn’t get out early.

Never happened. Lew and I pretty much lost track of each other. I got transferred to the Hollywood Division, but I heard about it when he killed himself. That’s not what they called it, they said he was cleaning his gun and had an accident, but it’s funny how so many cops’d have a few drinks and decide they better give their gun a good cleaning.

That must have been around 1955. And it wasn’t more than one or two years later that the husband died in prison. It seems to me somebody stuck a knife in him, but I may not be remembering that right. Maybe it was natural causes.

Then again, in a state joint, getting a knife stuck in you is pretty much a natural cause.

Charles, is there anything more you want to say?

All these years I kept this strictly to myself. There were stretches when it was on my mind a lot, and other times I’d go months or years without thinking about it at all.

But I never said a word to anybody.

And maybe I should leave it that way.

Same token, all of these people are gone. I must be the only man alive even remembers any of them. Why do I have to keep their secret?

Thing is, I don’t even know what I know. Not for certain.

Uh, Charles—

No, this is what, oral history? What you call it?

Only way to say it is to say it.

When I’m in the living room, what I hear is a snapping sound. Like a twig breaking. It’s faint, it’s coming from the back of the house, and if I’m outside where I’m supposed to be I most likely don’t hear it at all.

And after the twig snaps, there’s like a little sigh. Like the air going out of something.

“I think she’s gone.” That’s what he said, and as soon as I heard the words I knew she was gone, and I realized I knew it from the moment I heard the twig snap.

The twig?

Easy to call it that, but I don’t remember seeing any twigs in that bedroom.

I didn’t say anything, and Lew didn’t say anything, and then one night he did. Slow night, quiet night, and we’re in the car. I remember he was driving that night.

Out of the blue he says, “There’s people in this world who never have a chance.”

I knew he was talking about her.

I just sat there, and a minute or two later he says, “Say she pulls through. So he kills her next time, or the time after that. Or the twentieth time after that. You call that a life, Charlie?”

“No.”

We caught a red light. More often than not what we’d do is slow down enough to see there was no cross traffic and then coast on through it, but this time he braked to a stop and waited for the light to change.

And while he was waiting he took his hands off the wheel and sat there looking at ‘em.

The light went to green and we moved on. Two, three blocks along he said, “This way she’s in a better place. And he’s where he belongs. You don’t know what I’m talking about, do you, Charlie?”

“No,” I said. “No idea.”

It wasn’t that much longer before they moved me to the Hollywood Division, which was an interesting place to be in those days. Not that you didn’t get domestics there, too, and every other damn thing, but the people were a little different. The same in many ways, but a little different.

Where was I?

Uh, the Hollywood Division.

No, before that. Never mind, I remember. It was maybe another month I was with Lew, before the move to Hollywood. And he never brought up the subject again, and I for sure never said anything, but there was one thing he kept doing, and it made me glad when they transferred me. I’d have been glad anyway, because the move amounted to a promotion, but it gave me a particular reason to be glad to get out of that particular radio car.

What he would do, he’d go silent and look at his hands. And I couldn’t see him do that without picturing those hands taking hold of that woman’s head and breaking her neck.

I guess he saw the same thing.

And is that why he sat up late one night, all by himself, and gave his gun a good cleaning? Maybe yes, maybe no. The things he supposedly did during the Zoot Suit Riots, far as I know he had no trouble living with them, or the other three Mexicans he killed, and he might have been the same way with this.

Because, you know, it was the only way that woman was gonna get out of it, the mess she was in. Look at it that way and he was doing the humane thing. And it was the perfect opportunity, because her husband already thought she was dead and that he’d killed her. So this way she’s out of it, and this way he goes away for it, and that’s the end of it.

So would it make Lew kill himself a few years down the line? My guess is it wouldn’t. My guess is he was feeling low one night, and he took a long look at his life, not what he’d done but what he had to look forward to.

Stuck the gun in his mouth just to see how it felt.

Here’s something else I never told anybody. I been that far myself. I remember the taste of the metal. I remember—now, I haven’t thought of this in ages, but I remember thinking I had to be careful not to chip a tooth. One trigger pull away from the next world and I’m worried about a chipped tooth.

I never broke any woman’s neck, or shot any Mexicans, or did any big things that weighed all that heavy on my mind. But looking at it one way, Lew pulled the trigger and I didn’t, and on that score that’s all the difference there was between us.

Of course that don’t mean I won’t go home now and do it. I’ve still got a gun. I guess I can clean it any time I have a mind to.

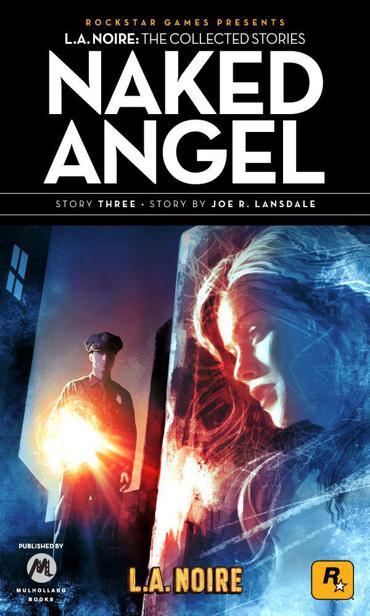

Naked Angel

Joe R. Lansdale

Deep in the alley, lit by the beam of the patrolman’s flashlight, she looked like a naked angel in midflight, sky-swimming toward a dark heaven.

One arm reached up as if to pull air. Her head was lifted and her shoulder-length blond hair was as solid as a helmet. Her face was smooth and snow white. Her eyes were blue ice. Her body was well shaped. One sweet knee was lifted like she had just pushed off from the earth. There was a birthmark on it that looked like a dog paw. She was frozen in a large block of ice, a thin pool of water spreading out below it. At the bottom of the block, the ice was cut in a serrated manner.

Patrolman Adam Coats pushed his cop hat back on his head and looked at her and moved the light around. He could hear the boy beside him breathing heavily.

“She’s so pretty,” the boy said. “And she ain’t got no clothes on.”

Coats looked down at the boy. Ten, twelve at the most, wearing a cap and ragged clothes, shoes that looked as if they were one scuff short of coming apart.

“What’s your name, son?” Coats asked.

“Tim,” said the boy.

“Whole name.”

“Tim Trevor.”

“You found her like this? No one else was around?”

“I come through here on my way home.”

Coats flicked off the light and turned to talk to the boy in the dark. “It’s a dead-end alley.”

“There’s a ladder.”

Coats popped the light on again, poked it in the direction the boy was pointing. There was a wall of red brick there, and, indeed, there was a metal ladder fastened up the side of it, all the way to the top.

“You go across the roof?”

“Yes, sir, there’s a ladder on the other side, too, goes down to the street. I come through here and saw her.”

“Your parents know you’re out this late?”

“Don’t have any. My sister takes care of me. She’s got to work, though, so, you know—”

“You run around some?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You stay with me. I’ve got to get to a call box, then you got to get home.”

Detective Galloway came down the alley with Coats, who led the way, his flashlight bouncing its beam ahead of them. Coats thought it was pretty odd they were about to look at a lady in ice and they were sweating. It was hot in Los Angeles. The Santa Ana winds were blowing down from the mountains like dog breath. It made everything sticky, made you want to strip out of your clothes, find the ocean, and take a dip.

When they came to the frozen woman, Galloway said, “She’s in ice, all right.”

“You didn’t believe me?”

“I believed you, but I thought you were wrong,” Galloway said. “Something crazy as this, I thought maybe you had gone to drinking.”

Coats laughed a little.

“Odd birthmark,” Galloway said.

Coats nodded. “I couldn’t figure if this was murder, vice, or God dropped an ice cube.”

“Lot of guys would have liked to have put this baby in their tea,” Galloway said.

The ice had begun to melt a little, and the angel had shifted slightly.

Galloway studied the body and said, “She probably didn’t climb in that ice all by herself, so I think murder will cover it.”

When he finished up his paperwork at the precinct, Coats walked home and up a creaky flight of stairs to his apartment.

Apartment.

The word did more justice to the place than it deserved. Inside, Coats stripped down to his underwear, and, out of habit, carried his holstered gun with him to the bathroom.

A few years back a doped-up goon had broken into the apartment while Coats lay sleeping on the couch. There was a struggle. The intruder got the gun, and though Coats disarmed him and beat him down with it, he carried it with him from room to room ever since. He did this based on experience and what his ex-wife called

trust issues

.

Sitting on the toilet, which rocked precariously, Coats thought about the woman. It wasn’t his problem. He wasn’t a detective. He didn’t solve murders. But still, he thought about her through his toilet and through his shower, and he thought about her after he climbed into bed. How in the world had she come to that? And who had thought of such a thing, freezing her body in a block of ice and leaving it in a dark alley? Then there was the paw print. It worried him, like an itchy scar.

It was too hot to sleep. He got up and poured water in a glass and came back and splashed it around on the bedsheet. He opened a couple of windows over the street. It was louder but cooler that way. He lay back down.

And then it hit him.

The dog paw.

He sat up in bed and reached for his pants.

Downtown at the morgue the night attendant, Bowen, greeted him with a little wave from behind his desk. Bowen was wearing a white smock covered in red splotches that looked like blood but weren’t. There was a messy meatball sandwich on a brown paper wrapper in front of him, half eaten. He had a pulp-Western magazine in his hands. He laid it on the desk and showed Coats some teeth.

“Hey, Coats, you got some late hours, don’t you? No uniform? You make detective?”

“Not hardly,” Coats said, pushing his hat up on his forehead. “I’m off the clock. How’s the reading?”

“The cowboys are winning. You got nothing better to do this time of morning than come down to look at the meat?”

“The lady in ice.”

Bowen nodded. “Yeah. Damnedest thing ever.”

“Kid found her. Came and got me,” Coats said, and he gave Bowen the general story.

“How the hell did she get there?” Bowen said. “And why?”

“I knew that,” Coats said, “I might be a detective. May I see the body?”

Bowen slipped out from behind the desk and Coats followed. They went through another set of double doors and into a room lined with big drawers in the wall. The air had a tang of disinfectant about it. Bowen stopped at a drawer with the number 28 on it and rolled it out.

“Me and another guy, we had to chop her out with ice picks. They could have set her out front on the sidewalk and it would have melted quick enough. Even a back room with a drain. But no, they had us get her out right away. I got a sore arm from all that chopping.”

“That’s the excuse you use,” Coats said. “But I bet the sore arm is from something else.”

“Oh, that’s funny,” Bowen said, and patted the sheet-covered body on the head. The sheet was damp. Where her head and breasts and pubic area and feet pushed against it there were dark spots.

Bowen pulled down the sheet, said, “Only time I get to see something like that and she’s dead. That don’t seem right.”

Coats looked at her face, so serene. “Roll it on back,” he said.

Bowen pulled the sheet down below her knees. Coats looked at the birthmark. The dog paw. It had struck a chord when he saw it, but he didn’t know what it was right then. Now he was certain.

“Looks like a puppy with a muddy foot stepped on her,” Bowen said.

“Got an identity on her yet?” Coats asked.

“Not yet.”

“Then I can help you out. Her name is Megdaline Jackson, unless she got married, changed her last name. She’s somewhere around twenty-four.”

“You know her?”

“When she was a kid, kind of,” Coats said. “It was her older sister I knew. That birthmark, where I had seen it, came to me after I got home. Her sister had a much smaller one like it, higher up on the leg. It threw me because I knew she wasn’t the older sister, Ali. Too young. But then I remembered the kid, and that she’d be about twenty-four now. She was just a snot-nosed little brat then, but it makes sense she would have inherited that mark same as Ali.”

“Considering you seem to have done some leg work in the past, that saves some leg work of another kind.”

“That ice block,” Coats said. “Seen anything like it?”

“Nope. Closest thing to it was we had a couple of naked dead babes in alleys lately. But not in blocks of ice.”

“All right,” Coats said. “That’ll do.”

Bowen pulled the sheet back, said, “Okay I turn in who this is, now that you’ve identified her?”

Coats studied the girl’s pale, smooth face. “Sure. Any idea how she died?”

“No wounds on her that I can see, but we got to cut her up a bit to know more.”

“Let me know what you find?”

“Sure,” Bowen said. “But that five dollars I owe you for poker—”

“Forget about it.”

Coats drove to an all-night diner and had coffee and breakfast about the time the sun was crawling up. He bought a paper off the rack in the diner, sat in a booth, and read it and drank more coffee until it was firm daylight; by that time he had drank enough so he thought he could feel his hair crawling across his scalp. He drove over where Ali lived.

Last time he had seen Ali she had lived in a nice part of town on a quiet street in a tall house with a lot of fine trees out front. The house was still there and so were the trees, but the trees were tired this morning, crinkled, and darkened by the hot Santa Ana winds.

Coats parked at the curb and strolled up the long walk. The air was stiff, so much so you could have buttered it like toast. Coats looked at his pocket watch. It was still pretty early, but he leaned on the doorbell anyway. After a long time a big man in a too-tight jacket came and answered the door. He looked like he could tie a knot in a fire poker, eat it, and crap it out straight.

Coats reached in his pants pocket, pulled out his patrol badge, and showed it to him. The big man looked at it like he had just seen something foul, went away, and after what seemed like enough time for a crippled mouse to have built a nest the size of the Taj Mahal, he came back.

Coats made it about three feet inside the door with his hat in his hand before the big man said, “You got to wait right there.”

“All right,” Coats said.

“Right there and don’t go nowhere else.”

“Wouldn’t think of it.”

The big man nodded, walked off, and the wait was started all over again. The crippled mouse was probably halfway into a more ambitious project by the time Ali showed up. She was wearing white silk pajamas and her blond hair looked like stirred honey. She had on white house slippers. She was so gorgeous for a moment Coats thought he might weep.

“I’ll be damned,” she said, and smiled. “You.”

“Yeah,” Coats said. “Me.”

She came over smiling and took his hand and led him along the corridor until they came to a room with a table and chairs. He put his hat on the table. They sat in chairs next to one another and she reached out and clung to his hand.

“That’s some butler you got,” Coats said.

“Warren. He’s butler, bodyguard, and makes a hell of a martini. He said it was the police.”

“It is the police,” Coats said. He took out his badge and showed it to her.

“So you did become a cop,” she said. “Always said you wanted to.”

She reached up and touched his face. “I should have stuck with you. Look at you, you look great.”

“So do you,” he said.

She touched her hair. “I’m a mess.”

“I’ve seen you messy before.”

“So you have, and fresh out of bed, too.”

“I saw you while you were in bed,” he said.

She didn’t look directly at him when she said, “You know my husband, Harris, died, don’t you?”

“Old as he was when you married him,” Coats said, “I didn’t expect him to outlive you. Of course, he had a lot of young friends and they liked you, too.”

“Don’t talk that way, baby,” she said.

As he thought back on it all, bitterness churned inside Coats for a moment, then settled. They had had something together, but there had been one major holdup. His bank account was lower than a snake’s belly, and the best he wanted out of life was to be a cop. The old man she married was well-heeled and well connected to some rich people and a lot of bad people; he knew a lot of young men with money, too, and Ali, she saw it as an all-around win, no matter how those people made their money.

In the end, looks like they both got what they wanted.

“This isn’t a personal call, Ali,” Coats said. “It’s about Meg.”

And then he told her.

When he finished telling her, Ali looked stunned for a long moment, got up, walked around the table as if she were searching for something, then sat back down. She crossed her legs. A slipper fell off. She got up again, but Coats reached up and took her hand and gently pulled her back to the chair.

“I’m sorry,” Coats said.

“You’re sure?” she asked.

“The dog paw, like you have.”

“Oh,” she said. “Oh.”

They sat for a long time, Coats holding her hand, telling her about the block of ice, the boy finding it.

“Any idea who might have wanted her dead?” Coats asked.

“She had slipped a little,” Ali said. “That’s all I know.”

“Slipped?”

“Guess it was my fault. I tried to help her, but I didn’t know how. I married Harris and I had money, and I gave her a lot of it, but it didn’t help. It wasn’t money she needed, but what she needed I didn’t know how to give. The only thing I ever taught her was how to make the best of an opportunity.”

Coats looked around the room and had to agree about Ali knowing about opportunity. The joint wasn’t quite as fancy as the queen of England’s place, but it would damn sure do.

“I couldn’t replace Mother and Father,” she said. “Them dying while she was so young. I didn’t know what to do.”

“You can’t blame yourself,” Coats said. “You weren’t much more than a kid.”

“I think I can blame myself,” she said. “And I will.”

Coats patted her hand. “Anyone have something against her?”

“She had gotten into dope, and she had gotten into the life,” Ali said. “I tried to pull her out, but she wasn’t coming. I might as well have been tugging on an elephant’s trunk, trying to drag the beast uphill. She just wouldn’t come out.”

“By the life, you mean prostitute?” Phillip asked.

Tears leaked out of Ali’s eyes. She nodded.

“Where’d she do her work?”

“I couldn’t say,” she said. “She was high-dollar, that’s all I know.”

Coats comforted her some more. When he was ready to leave, he picked up his hat and she walked him to the door, clutching his arm like a life preserver, her head on his shoulder.