Lamplighter (23 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

“Young lady!” Mister Humbert called long-sufferingly. “You might be the only lass at prenticing, but don’t think you’ll have special concession from me. Please turn around and refrain from disturbing the others.”

Skipping the sit-down meal at middens, Rossamünd grabbed some slices of pong and hurried to Door 143 in the Low Gutter and his promised visit with Numps. The Gutter was busier on a normal day, and Rossamünd had to negotiate the bustle of laborers and servants and soldiers. He entered the lantern store quietly and heard speaking: not one of the soft monologues of Numps, but the voice of a learned man.

Rossamünd became very still and listened.

“. . . Poor old Numps wouldn’t tolerate Mister Swill, eh?” the voice declared. It sounded like Doctor Crispus. He must have returned from his curative tour. “I must say I can barely compass the man myself: entirely too wily, all secrets and heavy-lidded looks and smelling of some highly questionable chemistry . . .”

Although he was aware that it would be proper to make his presence known to the speaker, a guilty fascination held Rossamünd and he remained tense and quiet.

“. . . Coming with his uncertain credentials, when all the while a proper young physic might have been satisfactorily summoned from the fine physacteries of Brandenbrass or Quimperpund. A product of the clerical innovations of that Podious Whympre. Everything in triplicate and quadruplicate and quintuplicate now! One thousand times the paperwork for the most trifling things, and all requiring our Earl-Marshal’s mark. How the poor fellow bears with the smother of chits and ledgers is beyond me: my own pile near wastes half my day!”

As Rossamünd moved to the end of the aisle he found it was indeed Doctor Crispus, sitting on a stool and ministering to the dressings on the glimner’s foot with intense concentration. He had examined Rossamünd on the prentice’s very first day as a lamplighter, and had had naught to do with him since. Numps was sitting meekly on a barrel waiting for the physician to finish. He looked up at Rossamünd before the lad had made a sound and smiled in greeting. The physician himself had still not noticed Rossamünd.

“Ah, Doctor Crispus?” the prentice tried, shuffling his feet to add emphasis.

With a start, the physician stood and quickly turned, catching at his satchel as it slid from his lap.

“I have come to help Mister Numps again,” Rossamünd added.

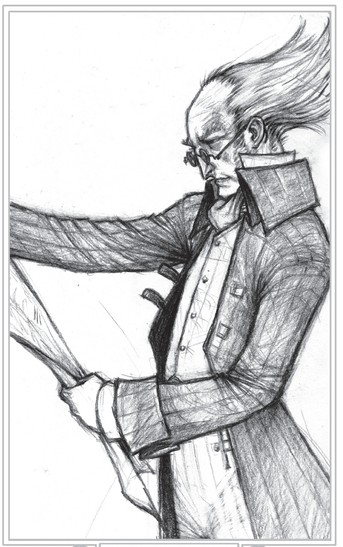

“Cuts and sutures, lad!” Crispus exclaimed with a flustered cough. “You gave me a smart surprise!” A towering, slender man—Doctor Crispus must have been the tallest fellow in the whole fortress and probably of all Sulk End and the Idlewild too—he was sartorially splendid in dark gray pinstriped silk, wearing his own snow-white hair slicked and jutting from the back of his head like a plume. He wore small spectacles the color of ale-bottles, and a sharp, intelligent glimmer in his eye boded ill for any puzzle-headed notions. “Ah, hmm . . .” The man composed himself. “Master Bookchild, is it not?”

“Aye, Doctor,” the prentice answered with a respectful bow. “At your service, sir,” he added.

“And so you have been, Master Bookchild,” the physician said, clicking his heels and giving a cursory nod, “of service to me, and more so to this poor fellow here, as I understand it.” He gave a single, paternal pat on Numps’ shoulder.

Numps hung his head and smiled a sheepish smile.

Rossamünd did not know what to say, so he simply said, “Aye, Doctor.”

“See, Mister Doctor Crispus, see: Mister Rossamünd has come back again and Numps has a new new old friend.They let him in, did you know? They never let my friends like him in before, did they? Maybe one day they’ll let the sparrow-man in too?”

Crispus smiled ingratiatingly. “Yes, Numps, yes. I see.”

Baffled but deeply gratified by this reception, Rossamünd asked, “How is your foot today, Mister Numps?” The bandages seemed still tightly bound and in their right place.

“Oh, poor Numps’ poor foot,” Numps sighed. “It hurts, it itches. But Mister Doctor Crispus told me well stern this morn that I was to

leave it be

. . . so I leave it be.” He wiggled his toes.

leave it be

. . . so I leave it be.” He wiggled his toes.

“And so you must.” Distractedly the physician pulled a fob from his pocket. “Ah! Middens is already this ten minutes gone,” he declared. “I must eat like any man jack.”

DOCTOR CRISPUS

“Doctor Crispus?” Rossamünd dared.

“Yes, Master Bookchild, quickly now: middens is not the meal to be missed. Breakfast maybe, mains surely—but never middens.” Crispus took off his glasses and dabbed at them with the hem of his sleek frock coat.

“Was Mister Numps right not to want to go to Swill?” Rossamünd inquired.

The physician nearly blushed. “Oh . . . Heard my complaints, did you?” He paused thoughtfully for several breaths. “Please disregard an unguarded moment. Those were just professional frustrations requiring a little letting. It’s a small understanding between Numps and I—whenever we meet: I run away at the mouth, he listens. That being so,” Doctor Crispus carefully continued, “I would rather you came to me with your ills, or the dispensurist or even Obbolute if I’m incommunicado; or just go sick until I return, than put yourself into the hands of that hacksaw.” With a cough Crispus looked Rossamünd square in the eye. “I would thank you not to say any more of that which you have overheard.”

Rossamünd ducked his head, going shy from the confidence this eminent adult was putting in him. “Not a word, Doctor.” He nodded gravely.

“How-be-it, eating is overdue.” Doctor Crispus pointed at Numps’ legs. “I have applied new bandages but that is all: your use of the siccustrumn was exactly right. The lacerations are deep but the potive has been well applied and is doing the healing work far better than any I could now. You have been given charge over a salumanticum for good reason, prentice-lighter.”

Rossamünd bowed again, unable to hide his grin of delight.

“Enough now, food awaits.” Doctor Crispus gathered up his satchel and stray instruments. “After that it’s back to that stout fellow, Josclin—may his skies seldom cloud.”

“Is he mending, Doctor?” Rossamünd ventured.

“If you are a wagering man, Master Bookchild,” Crispus said as he began his exit, “I would put my haquins and carlins on Mister Josclin’s full recovery! Good diem to you and good diem to you, Mister Numps. I shall return in a few days to ensure your clever foot—as you call it—is still mending. I have seen you return from the very doors of death, my man.Your foot will not unduly trouble you.”

With that the physician hustled out of the lantern store.

Numps immediately began cleaning panes. “Mister Doctor Crispus and Mister ’Pole doesn’t know all what happened.” The glimner did not look up, but spoke into his own lap.

There was a long pause.

“Doesn’t know what?” the prentice pressed as gently as he could.

“He didn’t tell it like things happened . . .” The glimner went on. “I didn’t go a-crawling back to the lamppost . . .”

Realizing what Numps was talking about, Rossamünd leaned a little closer.

“I remember . . . Even now when I sleep I remember. Poor Numps was dead in his puddle of red, no crawling about for him. It was the little sparrow-man that helped me.”

Rossamünd’s attention prickled. “The little sparrow-man, Mister Numps?” he asked very very quietly. This was the type of talk that could get you branded “sedorner.”

“Yes, yes.” Numps smiled, looking up at last. “They might have got my arm to gnaw on, but they didn’t get all of poor Numps. It was the little sparrow-man that fought the pale, runny men—”

“I heard you were hurt by rever-men!”

“Oh aye, aye! Pale, runny men ripping us all to stuff and bits and that little sparrow-man came and tore

them

limb from limb and saved me—my first new old friend. He plugged all the pains with weeds and stopped the red from its flow-flow-flowing . . . Fed me dirty roots. That made me feel safe.”

them

limb from limb and saved me—my first new old friend. He plugged all the pains with weeds and stopped the red from its flow-flow-flowing . . . Fed me dirty roots. That made me feel safe.”

“That little sparrow-man?” Rossamünd repeated.

“Aye, this big”—still gripping a pane, Numps adumbrated a creature of short stature with his hand—“and with a large head like a sparrow’s, a-blink-blink-blink.”

A hunch tickled at the back of Rossamünd’s mind.

Could it be the same creature?

“I think I have seen him myself,” he said.

Could it be the same creature?

“I think I have seen him myself,” he said.

Numps became all attention, and he too bent forward in his seat.

“Not a long time ago I spied him,” Rossamünd continued, “on the side of the Gainway going down to High Vesting, a nuglung with a sparrow’s head all dark about the eyes and white on his chest, blinking at me from a bush.”

A little taken aback, Numps blinked quickly. “Yes yes, Cinnamon—he helped me! I reckon he’s got more names than I’ve got space in my limpling head to count, he’s been about for so, so long . . . Long-living monsters with long lists of names.”

Cinnamon,

Rossamünd marveled. “How do you know this, Mister Numps?” he whispered.

Rossamünd marveled. “How do you know this, Mister Numps?” he whispered.

“Hmm, well, because he told me,” Numps answered simply. “Cinnamon is poor Numps’ friend too, see, ’cause it was him that beat the runny men.”

Rossamünd felt something between awe and a habitual, thoughtless horror. “You are friends with a

nuglung

?” he breathed, reflexively looking over his shoulder for unwelcome listeners.

nuglung

?” he breathed, reflexively looking over his shoulder for unwelcome listeners.

Numps grinned. “Ah-huh. Cinnamon said he was come from the sparrow-king who lives down in the south hills. He keeps an eye out for old Numps, sends his little helpers to watch.”

“The sparrow-king?” Rossamünd scratched his face in bewilderment. His thoughts reeled at the thought of a monster-lord living near.

“Yes yes,” Numps enthused. “The Duke of Sparrows, the sparrow-duke; he has lots of names too.

The Sparrowling

Is an urchin-king

Who rules from courts of trees.

He guards us here

From the Ichormeer

And keeps folks in their ease.”

Is an urchin-king

Who rules from courts of trees.

He guards us here

From the Ichormeer

And keeps folks in their ease.”

“Have you seen the Duke of Sparrows, Mister Numps?”

Numps shook his head. “But I would like to, though.”

“So would I,” Rossamünd admitted.

“But you can see him anytime, Mister Rossamünd!” The glimner pulled a perplexed face. “All the old friends would be your friends, wouldn’t they?”

The young prentice hesitated. “All the

old

friends? What do you mean, Mister Numps?”

old

friends? What do you mean, Mister Numps?”

“Yes, yes! My poor limpling head—the nuggle-lungs and glammergorns and the other old friends.”

“I—I have one old friend such as this,” Rossamünd dared. “His name is Freckle. He is a glamgorn who helped me when we were trapped in a boat with a rever-man. We set Freckle free.”

Numps listened to this short telling with growing intensity. At its conclusion he grinned rapturously and did a little sit-down dance, chiming,

“Yes yes, you set him free,

trapped in gaol is no place to be.

trapped in gaol is no place to be.

. . . you are a good friend indeed for Numps to have who sets his fellows loose from traps. Good for Freckle too.”

“I don’t like to tell anyone about him,” Rossamünd warned. “You should not say either, Mister Numps, about Freckle or Cinnamon. Most people don’t like those who are kind to nickers.”

Numps’ enthusiasm vanished. “I remember that folks hate the nuggle-lungs.” He nodded glumly. “And the hobble-possums and all the gnashers, friend or bad. I remember that them that talk with them nor think them friends are hated too. Don’t be a-worrying and a-fretting, I won’t say naught ’bout Cinnamon nor Freckle, and I’ll not say naught ’bout you neither.”

They set to polishing panes again, Numps redoing Rossamünd’s as he had done the day before.This time the prentice did not mind. He was already being wooed by the timber-and-seltzer-perfumed ease of the lantern store, the rumble of rain on its shingle roof adding a merry, monotonous melody. It was with profound reluctance that he returned to his usual tasks at middens’ end.

12

PUNCTINGS AND POSTERS

Other books

Journey in Time (Knights in Time) by Karlsen, Chris

In God's House by Ray Mouton

The Legacy of Buchanan's Crossing by Rhodan, Rhea

Come Monday by Mari Carr

Midnight Dolls by Kiki Sullivan

Frey by Wright, Melissa

My Sweet Valentine by Annie Groves

All Due Respect Issue 2 by David Siddall, Scott Adlerberg, Joseph Rubas, Eric Beetner, Mike Monson

Lovers and Other Strangers Box Set: The Boston Stories by L.C. Giroux

Puckoon by Spike Milligan