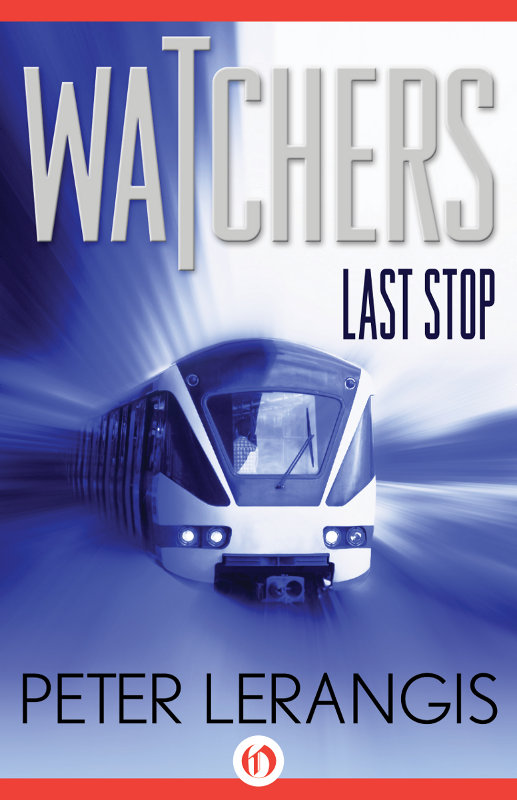

Last Stop

Authors: Peter Lerangis

Peter Lerangis

To George Nicholson, who brought the idea to life;

Herb Strean, who provided a place for it to grow;

David Levithan, who gave it wings;

And, always, Tina, Nick, and Joe, who give it meaning.

WATCHERS

Case File: 3583

Name: David Moore

Age: 13

First contact: 33.35.67

Acceptance:

He’s not ready.

H

ERE’S WHAT

I

REMEMBER

most:

Heat.

You could see it rising from the pavement in waves.

Humidity.

It slid off your skin, like hot oil off a skillet.

Anger.

Mine. At everything.

Mostly at my friends—Heather, Max, and Clarence. They’d talked me into riding the subrail home. On the last day of the work week. When all the Franklin City municipal workers leave their offices early—exactly when we middle-school kids leave classes.

I hate crowds. I hardly ever ride the sub.

On this day each week, my dad used to give me a ride in a squad car. He worked for the city, too. He was a case solver in the Public Guardian Department.

But I hadn’t had any rides home in six months. So there I was, standing shoulder to shoulder, dripping wet, on the putrid-smelling platform of the Booker Street station. Which leads to the other major reason I was angry.

Dad.

In fact, Dad was all I ever thought about. In class. At home. Whenever the voicephone rang. I’d picture him, and all I wanted to do was scream.

Which wasn’t fair, really.

For one thing, he was a nice guy. I loved him.

For another thing, he was dead.

Six months earlier, he’d left my mom and me. He got out of bed, dressed himself, and kissed Mom good-bye. When she asked where he was going, all he said was “Home.”

He never came back.

Dad was already totally off his konker by then. It had started with headaches, about a year and a half ago. Then sudden blackouts at odd times. Soon he was forgetting simple things. Talking baby talk. Taking walks and ending up in some stranger’s swimming pool in a neighboring town. Doctors checked him for everything—blood clots, tumors, Fassbinder’s disease. They thought it might be inherited, but Dad had no family records at all. He was an orphan and didn’t even know where his parents had come from.

Whenever Dad strayed, Mom called the pugs, the good old Public Guardians. They would always bring him back. They were Dad’s loyal buddies.

But this time, the pugs came up empty-handed. They contacted other departments in suburbs nearby. Eventually the search spread to include the whole country. A reward was posted for anyone who sighted Dad.

Soon the radio call-in shows started. The TV talk shows.

Tons of people thought they had seen him. Fishing in the Palm Tree Lakes. Moose hunting. Heading a religious cult. Hiding in a cave.

But every lead checked out false.

Mom tried to be optimistic. She began going to this therapy group. (She thought I should, too, but I said

no way

.)

For weeks, I didn’t sleep. Whenever I closed my eyes, I saw Dad. Walking into my room. Sitting at the foot of the bed. Smiling.

Then my eyes would pop open. And he’d be gone.

I tried to believe that Dad was alive. But that made me feel horrible. Because if he

were

alive, that meant he didn’t want to see us. Or he didn’t remember us. Or worse.

When the pugs gave up, I knew it was all over. I could tell by the way they looked at me, all soft and pitying. If Dad had been found, we’d have known about it. His face had been broadcast coast-to-coast.

I tried to forget. I plunged into homework, chores, school activities—all so I wouldn’t have time to think of him.

The worst part? He hadn’t said good-bye to me. In dreams

I

would say that to him, over and over. But he’d just smile.

I kept seeing him everywhere. In shadows and shop aisles. In ball fields and on bikes.

He’d left me. But he wasn’t leaving me alone.

So the anger crept in. And grew.

As I stood at the subrail station, the feelings were balling up in my head. Like a fist.

Sweat prickled my neck. My shirt was soaked. I knew that when I got home, Mom would make me take a shower. We had to appear on a local TV show that afternoon. To talk about Dad, of course.

I hated those shows. I hated being an object of pity. Answering dumb questions.

And to make matters worse, my friends were acting like total idiots. Giggling. Making fart noises.

I stepped away. And I saw a familiar figure. To my right. A man in a blue shirt, trudging down the subrail stairs, face buried in a newspaper.

Dad.

My heart jumped. I spun to face him.

Then he put the paper down. And my eyes locked with those of an ashen-faced, annoyed stranger.

Again.

How many times had this happened? A hundred?

And each time as painful as the last.

I felt pressure behind my eyelids.

Tears.

I was not going to cry. I’d vowed not to. For six long months I had kept it in.

The crowd on the platform thickened. I could hear a distant rumbling. I leaned over the edge and saw two pinpoints of light approaching in the tunnel darkness.

The train screeched into the station. The cars were already packed. Everyone behind us began to shove as the door opened.

A sudden memory. I’m running to catch the train with Dad. I’m five years old. Dad races ahead and reaches the car door first. He turns to face me, holding out his arms and legs in an X-shape. The door begins to close on him and I scream. I scream because I think he is going to die

…

Stop.

I had to stop thinking.

Heather and Clarence squeezed in first. Max and I made it just as the door slid closed on our backs.

Heather could barely reach the handrail above her head. Next to her a sweaty bearded guy was holding a newspaper in her face.

The man next to me must have had slugs with garlic for lunch. The odor was knocking me out.

As the train picked up speed, I turned away. Now I was facing the door. I stared blankly through the window, trying to hold my breath. I felt sick.

Then the train stopped.

Cold. In the tunnel.

The overhead fluorescents blinked off. Instantly the car was pitch-black. Muffled groans rose all around me.

Claustrophobia.

I felt icy cold. I couldn’t see the bodies around me but I heard them. Breathing loud, like handsaws. Breathing-machines. Closing in on me…

Where were we?

Between the Booker and Deerfield Street stops.

Granite Street.

I remembered. The old, abandoned station. It was here, somewhere. We used to watch for it when we were kids. The long platform lit by three bare lightbulbs. The grimy tiles spelling out “Granite.” The yellowed, graffiti-covered walls. The floor with a carpet of dust.

Look for it.

Yes. Keep my mind off the claus

off the

Lights.

Lights?

Outside the window.

The platform, the walls, the floor. Gleaming. Like a movie set.

Yes. They filmed down here. Often.

But they couldn’t have set it up so fast.

I rubbed my eyes. I blinked.

Claustrophobia. Panic. Visions.

Still there.

Ads cried out from the walls. Movies I’d never heard of. Odd names. Phrases that made no sense, like “us open.”

People, too. Dozens. Dressed in funny clothes. Not ugly, just…off. The colors, the cut of the pants, the lengths of the skirts.

Off.

On the walls, a mosaic of purple tiles spelled out the name of the station.

86

TH

STREET.

No. “Granite.” It was Granite Street.

The people on the platform were moving now. Toward the middle door of the car. Kids squealed, looking into

The car.

In the car, it was pitch-black. I felt bodies, I heard the breathing. But I saw no one. Despite the brightness outside the window.

How?

None of the station’s light was penetrating inside. As if it were being absorbed and reflected at the same time.

I opened my mouth to say something— anything.

Then, a sudden

whoosh.

To my right.

The middle door of the car slid open. Through it poured

Light?

It was more than bright, somehow.

Loud

light. Solid.

A box of light.

Now I could see the passengers around me. I looked for the shock in their faces. The recognition that I wasn’t alone.

But all I saw was boredom. Annoyance. As if nothing had happened.

From among them, a man jostled into the light. A familiar man. I’d seen him on the train before, one of those thin, droopy people who always seem sad and afraid.

He clutched a small sky-blue business card. He cringed in the glare. But he was grinning.

The people on the platform let out a welcoming cheer. The man blinked. Eyes adjusting, he stepped through the door. His cheeks were streaked with tears.

The crowd swallowed him up, patting him on the back, hugging him, kissing him. He almost lost his cap. His business card floated to the ground.

Then the door closed. Again, blackness inside.

The train lurched forward, then stopped. The overhead lights flickered on, harsh and greenish-white.

“We are experiencing difficulty…” blared the conductor’s voice over the speakers.

The train began to move. The overhead lights winked, then went off again.

I kept my eyes on the station. The jubilant crowd was now leading the man up a flight of stairs. Except for one person. One man standing alone, peering at our train.

A scream caught in my throat. I grabbed at the rubber pads between the door and tried to yank them open, even though the car was moving.

That was when my father saw me. And he waved, until the train rolled out of sight.

Sometimes it just has to happen.

And that makes you ready.

D

AD.

The word exploded in my brain.

It couldn’t be.

But it

was.

It was Dad. He’d seen me.

My dad was alive.

SMMMACK! SMMMACK! SMMMACK!

I was banging on the door with my fists now.

“WAIT!”

My own voice, piercing and raw.

People were staring at me now. The guy with the garlic breath edged away. His face looked curdled. His eyes were darting nervously from me to the window.

The station was out of sight. Grimy subrail walls sped by, illuminated by the dull glow of an occasional lightbulb.

“Next stop, Deerfield!” the conductor’s voice blared over the speakers.

A dream.

Is it possible to have dreams when you’re wide-awake?

Of course.

Stress. That’s what it was.

Stress was making me see things. Like the guy in the blue shirt.

Maybe I was going crazy.

My friends definitely thought so. I could see that in their stunned expressions.

The train was slowing again as we approached the Deerfield Street station. One stop short of my own.

I felt humiliated. I had to get out. I was close enough to walk the rest of the way home, no pain.

When the doors opened, I slipped out. I sped through the station at a dead run, took the stairs three at a time, and dashed outside into daylight. Bright, clear daylight.