Last Team Standing (21 page)

Read Last Team Standing Online

Authors: Matthew Algeo

The Steagles' Roy Zimmerman tackles New York Giants end Will Walls during the Steagles' 28-14 victory over the Giants at Shibe Park, Philadelphia, October 9, 1943. Rushing to assist Zimmerman is his teammate, Ben Kish (44). Note the white football, which the NFL used in night games at the time.

Photo courtesy Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, PA

Al Wistert in 1940, his sophomore season at the University of Michigan. He was drafted by the Eagles in 1943.

Photo courtesy Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, PA

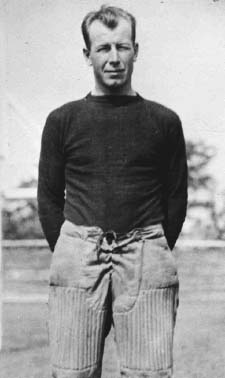

Bill Hewitt in the 1930s, when he played for the Chicago Bears. In 1943, Hewitt was coaxed out of retirement to play for the Steagles. A new rule required him to wear a helmet for the first time in his career.

Photo courtesy Pro Football Hall of Fame/

WireImage.com

Earle “Greasy” Neale shortly before he became the head coach of the Philadelphia Eagles in 1941. Neale shared head coaching duties with Pittsburgh's Walt Kiesling when the two teams merged in 1943.

Photo courtesy Pro Football Hall of Fame/

WireImage.com

Demonstrating their defensive prowess, the Steagles encircle Green Bay Packer Tony Canadeo at Shibe Park, Philadelphia, December 5, 1943. Among the Steagles are Tom Miller (89), Ed Conti (67), Tony Bova (85), and Ray Graves (52).

Photo courtesy Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, PA

Steagles halfback Jack Hinkle (43) runs for a touchdown against the Green Bay Packers at Shibe Park, Philadelphia, December 5, 1943. Blocking for Hinkle are Ben Kish (44) and Tony Bova (85).

Photo courtesy Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, PA

9

9 Chicago

ChicagoO

N

T

HURSDAY,

A

PRIL

8, 1943, the federal Office of Price Administration decreed that, effective the following Tuesday, the length of matchsticks would be decreased by roughly ten percent to conserve wood. The OPA also ordered match manufacturers to begin packing matches “half with the heads one way and half in the opposite direction,” thereby reducing the amount of paper required for packaging.

Four months later, six statuesque young women picketed the OPA offices in San Francisco to draw attention to the plight of “tall gals who cannot get long stockings.” “The new OPA ceiling on stockings is about 29 inches and they end slightly above the knees,” said one protester. “So we have to go barelegged and it ain't dignified.”

From the length of matchsticks to the length of stockings, the Office of Price Administration controlled virtually every facet of daily life in the United States during the war. The most obvious manifestation of this control was rationing. The massive amount of material needed to supply the armed forces led to shortages of everything from steel to soap.

At various times, the list of rationed goods included rubber, automobiles, typewriters, sugar, bicycles, gasoline, farm machinery, boots, oil, farm fences, coffee, oil and coal stoves, shoes,

processed foods (including juices and canned, frozen, and dried fruits and vegetables), firewood, liquor, canned milk, cigarettes, butter, meats, fats, and cheese.

Rationing was administered by the OPA through 5,500 local boards, similar to the draft boards. Each household was periodically issued a ration book, which contained rows of different colored stamps, each of which was assigned a point value and a letter. The OPA also assigned each rationed item a point value based on its scarcityâthe scarcer the item, the higher the point value. A consumer wishing to buy, say, pork chops, might be required to surrender 15 red “B” points in addition to the purchase price.

But no amount of rationing could prevent periodic shortages of certain goods. Newspapers were filled with stories of “famines”: butter famines, whiskey famines, beef famines, gasoline famines. A shortage of sheet steel led to a license plate famine in Pennsylvania. So, instead of issuing new plates during the war, the state distributed small metal tags that were attached to the old plates, a system that would be adopted permanently (with stickers replacing the metal tags) in the late 1950s. There was even a penny famine, owing to the military's demand for copper. The government responded by minting pennies out of steel in 1943, a development that drove consumers and shopkeepers crazy, since the shiny coins closely resembled dimes.

The booming wartime economy obliterated the remnants of the Great Depression. Inflation was the new concern. With many goods in short supply, prices would naturally rise. With workers in great demand, wages, too, would increase. Inflation would not only raise the cost of fighting the war; FDR feared it would also have a corrosive effect on morale. To keep a lid on it, the OPA froze the prices of many goods and services. The wages of many workers were likewise frozen.

No detail was too mundane to escape the scrutiny of the OPA. It imposed price controls on “the cutting and maintenance of lawns,” thus freezing the wages of kids who mowed yards for pocket change. In restaurants, the OPA ruled, diners were permitted a cocktail, soup, or dessertâbut not all three. On New Year's

Eve 1943, nightclubs were instructed to charge no more for drinks and meals than they had one year earlier. Minor violations of the rationing regulations usually resulted in a 30-day suspension of ration privilegesânot an insignificant penalty, given that many basic necessities were not legally obtainable without ration stamps. More serious violations, such as trafficking in black market goods or counterfeit ration stamps, were punishable by up to ten years' imprisonment and a $10,000 fine. It wasn't only patriotism that contributed to the program's high compliance rate.

The burden of coping with the inconveniences, sacrifices, and privations of wartime America fell most heavily upon women. With their husbands at war or at work, women assumed total management of the household. Propaganda campaigns specifically targeted women, urging them to “Use it up, wear it out, make it do or do without.” In

Don't You Know There's a War On?,

his seminal book about life on the home front, Richard Lingeman writes of the wartime woman: “She was a soldier and her kitchen a combination frontline bunker and rear-echelon miniature war plant.”