Last Team Standing (23 page)

Read Last Team Standing Online

Authors: Matthew Algeo

There was also the possibility that the players would be reclassified 1-A and inducted immediately. And it wasn't just the Bears who would be affected. A negative ruling would affect the entire league, and all of professional sports for that matter, since most teams employed players who worked in war plants during the offseason. If those players were not permitted to leave their war jobs, pro sports would be out of business. It was estimated that three-fourths of all major league baseball players were doing war work after the baseball season ended.

“It goes without saying, of course,” wrote

New York Herald Tribune

sportswriter Arthur E. Patterson, “that if these men were frozen to their war jobs, there just wouldn't be any baseball in 1944.”

One pro sports team, however, had no such concerns. Since the Steagles required all players to hold war jobs, the issue to them was moot.

“We turned our practices upside down to make sure that the men would not let their war work suffer,” Harry Thayer said, rather smugly, in reference to the investigation of the Bears. “I

venture to say that by the time we open our regular season ⦠every man on the squad will be in fact a full-time war worker and a part-time football player.”

Ralph Brizzolara met with William Spencer at the WMC office on September 23, just three days before the Bears opened the season in Green Bay. Elmer Layden met with Spencer the next day. Pending the outcome of the investigation, Spencer ruled that the five Bears in question would be allowed to play football. The team, meanwhile, launched a public relations counteroffensive. On October 8, it made a show of announcing that it would soon be losing four players to the military. Bill Geyer, Bill Osmanski, Johnny Siegal, and Bill Steinkemper would all be joining the Navy within three weeks.

G

EORGE

H

ALAS NOT ONLY OWNED

the Chicago Bears, he coached them, too. Except for three seasons in the early 1930s, when Ralph Jones took the reins, he was the team's only head coach from its founding in 1920 until the Navy recalled him halfway through the 1942 season. In his absence, Halas delegated the coaching duties to Luke Johnsos and Hunk Anderson, two former Bears who had also served as assistant coaches under Halas before his departure. Johnsos was in charge of the offense and Anderson oversaw the defense. It was an arrangement similar to Walt Kiesling and Greasy Neale's, with one added benefit: Johnsos and Anderson actually got along.

“The division could have caused trouble, but didn't,” Johnsos recalled. “Neither of us told the other what to do.”

Even without Halas at the helm, the Bears were nearly unstoppable. Since he'd left they'd lost just once, a 14-6 heart-breaker to the Redskins in the 1942 championship game. After opening the 1943 campaign with a 21-21 tie in Green Bay, the Bears defeated the Lions and the Cardinals by a combined score of 47-21. One of the Bears' stars was Bronko Nagurski, who'd retired at the end of the 1937 season, but was lured back in 1943. In his prime, Nagurski was a powerful fullback, so strong that more than one tackler was knocked unconscious trying to bring

him down. He was nearly 35 now, older even than Bill Hewitt, and not as fast as he used to be, so the Bears moved him to tackle, where he acquitted himself nicely.

“Bronk was still as strong as a bull,” writes his biographer, Jim Dent. “It took two strong men to move him, much less block him out of the play.” Nagurski returned to the Bears out of loyalty to Halas, as well as for the money: $500 a game, more than he'd ever made before.

The 1943 Bears continued Halas's tradition of playing smash-mouth football: “a crushing ground game and a weekly accumulation of sizeable penalties,” as the

Tribune's

Edward Prell put it. But they could also throw the ball. Quarterback Sid Luckman was leading the league in passing, and seven of the Bears' ten touchdowns so far in 1943 had been scored through the air. Luckman was a Columbia grad with a golden arm. He couldn't throw the ball very far or very hard, but he could throw it with stunning accuracy.

“He couldn't throw too good,” said Luckman's longtime teammate Clyde “Bulldog” Turner, “but he'd complete 'em.”

The Bears' increasing use of the pass led some to claim the club had “turned sissy” by “subordinating their running game to an aerial attack,” a charge that Luckman emphatically denied.

The Steagles-Bears game was rife with subplots. It would be a battle of the only two teams in the league running the T formation. Greasy Neale had learned the T by studying film of the Bears; now he hoped to give them a taste of their own medicine. The game also pitted the league's two best defenses against each other. The Steagles were No. 1 in run defense and overall defense, while the Bears were tops in pass defense. The game would also be a homecoming of sorts for Bill Hewitt, who had started his career with the Bears before being traded to the Eagles. Hewitt had not distinguished himself with his play in the Steagles' first two games and he was determined to make an impression against his old friends. The bookmakers favored Chicago, but the Steagles were confident and the Bears were wary.

“They've got a tough ball club,” Bears assistant coach Paddy

Driscoll said a few days before the game, “and we know we've got to get together and go to the limit on Sunday.”

S

ATURDAY,

O

CTOBER

16, 1943, was a red-letter day in Chicago. At 10:48 that morning, Mayor Edward J. Kelly snipped a red, white, and blue ribbon to formally open the city's first subway, a 4.9-mile stretch of tracks running underneath State Street. Chicago had wanted to build a subway since the turn of the century but couldn't afford to until FDR turned on the federal money spigot during the Depression. With a $23 million grant, the city constructed the most modern subway in the world, with a state-of-the-art ventilation system, escalators, and fluorescent lighting. A single, 3,500-foot platform, one of the longest in the world, connected every station between Lake and Congress streets. The stations themselves were designed in the Art Moderne style, each with a color scheme revealed in accents like light fixtures. And a ride cost just ten cents.

The ribbon-cutting ceremony took place in the Madison Street station. On the street above, thousands of Chicagoans braved a chilly north wind to witness a spectacular hour-long parade. The subway was a remarkable feat of engineering, given the city's soft, sandy substrate. It was also hailed as a way to take pressure off the city's overcrowded elevated trains, which carried up to a million passengers every day.

October 16 was a red-letter day in Chicago for another reason: it was on that day that William Spencer, the regional director of the War Manpower Commission, ruled that the five players who had left war jobs to join the Bears had

not

violated WMC regulations. Spencer ruled that the players were “under contract to the football club and subject to recall at the start of the season.” He also ruled that their “principal occupation” was football, so “any jobs accepted by the players during off-season periods constitute supplemental employment, not subject to WMC regulation.” In other words, it didn't matter whether they had certificates of availability. Spencer also pointed out that none of the players'

employers had complained to the WMC about their leaving at the start of the football season, “indicating they understood the services of the players were only on a temporary basis.” The five were free to keep playing ball, as were all other professional athletes who worked in war plants during the off-season. Bears fans were delighted. The team itselfâindeed all of professional sportsâwas simply relieved.

The Bears did get a bit of bad news that Saturday, however: their star tackle Bronko Nagurski had to hurry home to International Falls, Minnesota. His mother was ill, two of his farmhands had quit, and his father's grocery store was short of staff. To the Steagles, of course, this was very good news.

The next afternoon, nearly 22,000 curious fans ventured to Wrigley Field for a peek at the two-headed monster called the Steagles. Today it seems an unlikely venue for football, but Wrigley Field was the Bears' home for fifty seasons. When the team, then known as the Staleys (after the starch company that originally sponsored the team), moved from Decatur, Illinois, to Chicago in 1921, George Halas met with William L. Veeck, Sr., the president of the Chicago Cubs, to discuss renting Wrigley Field from the baseball team. Veeck wanted what was to become the standard rent for NFL teams in major league ballparks: 15 percent of the gate receipts and all concessions. Halas agreed, happy he didn't have to pay a fixed rent. With temporary bleachers erected in the outfield, the ballpark accommodated about 46,000 fans for football. After the 1970 season, the league passed a rule requiring all teams to play in venues with a minimum seating capacity of 50,000, forcing the Bears to move downtown to Soldier Field. Football and Wrigley Field were a good fitâbut a tight one. A gridiron barely fit within the “Friendly Confines.” In the outfield, one corner of the end zone came within inches of the brick outfield wall, which wasn't covered with ivy until 1937. Bronko Nagurski once crashed into the wall headfirst after scoring a touchdown. Back on the sidelines, Nagurski is said to have told Halas, “That last guy gave me quite a lick!” A corner of the

opposite end zone actually went into the first base dugout. The Bears eventually padded the outfield wall and laid foam rubber in the dugout to protect players.

The previous day's winds had died down, and the weather that Sunday was clear and cool, a delicious day for football. At two o'clock the Bears' Bob Snyder kicked off to the Steagles. Roy Zimmerman returned the kick to the Phil-Pitt 38. On first down, halfback Ernie Steele carried the ball two yards to the 40. On second down, Zimmerman tossed a long pass to Steele, who caught the ball on the Chicago 24 and ran it the rest of the way into the end zone. Zimmerman added the extra point, and just 80 seconds into the game the score was 7-0 Steagles. Wrigley Field was stunned into silence, but back at the Hotel Philadelphian loud shrieks of joy could be heard coming from one of the suites. As they did whenever the Steagles played away from Philadelphia, the players' wives had gathered to listen to the game on the radio.

After Steele's touchdown, Zimmerman kicked off to the Bears' Dante Magnani. Magnani had played for the Cleveland Rams in 1942. He was among the players distributed to the remaining clubs when the Rams folded for the season. The Bears literally picked his name out of a hat. Magnani took the kickoff on his own four-yard line. Somewhere around the 20 he burst through a wave of green-shirted Steagles and sprinted down the sideline. At the Phil-Pitt 12 he barely outran Ernie Steele's desperate lunge. After that, Magnani could have run into the dugout, through the locker room, and all the way down Addison Street to the lake, and still no Steagle would have caught him.

Magnani's 96-yard kickoff return opened the floodgates. The Bears scored six more touchdowns before the Steagles tacked on two meaningless fourth-quarter scores. The final was Chicago 48, Phil-Pitt 21. It was the most points the Bears had ever racked up against either the Steelers or the Eagles. (The fact that it was also the most points either Pennsylvania squad had ever scored against Chicago was no consolation.) The Bears scored three touchdowns on passes, two on runs, one on a kickoff return, and one on a

punt return. They rushed for 205 yards. The Steagles rushed for just 60. The Phil-Pitt line, so ballyhooed entering the game, “fell apart like a one-hoss shay,” according to the

Philadelphia Record.

Al Wistert, who started the game at right tackle, took some of the blame. It was the rookie's first NFL game back in his hometown. “I got over-anxious,” he recalled.

My main responsibility was to close the inside gap, between me and the guard next to me. Well, after a couple plays, I figured I would try to fake inside then slide outside, to stop the runner going that way, see. Well, Luckman figured out what was going on and they ran inside me a couple times. The linebacker expected me to close that gap, so they got good gains. I was going against Greasy's orders and he gave me hell after the game. He said, “Where were you today? You were supposed to stop the inside run!” And I said, “Well, I tried to slide outside. I guess I gambled and lost.” And he said, “You didn't lose; the team lost!”

It wasn't all Wistert's fault, of course. There was plenty of blame to go around. None of the linemen performed well; it was almost as if they'd forgotten how to block and tackle. The running backs spun their wheels all day. Roy Zimmerman completed just six of 24 passes. (Sid Luckman, meanwhile, completed 13 of 25.) The defeat was total. In the

Pittsburgh Press,

Cecil Muldoon called it a “humiliation.” To Jack Sell of the

Post-Gazette,

the game was “a long story of disaster.”

“They beat the pants off us,” was how Ernie Steele put it. Ted Doyle agreed.

“We got the hell beat out of us,” said Doyle. “You try to forget that type of game.”

The loss distressed Greasy Neale profoundly. In the locker room after the game, he lambasted the squad.

“You can't win ball games in this league by playing high school football!” he screamed. It was a long train ride home. At

least the Steagles wouldn't have to play the Bears againâunless they met in the championship game, a possibility that suddenly seemed much more remote.

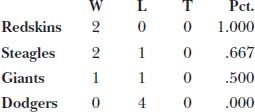

In Milwaukee, the Redskins had won their second straight game, throttling the Packers 33-7. And in New York, the Giants had clobbered the Dodgers 20-0, with rookie Bill Paschal scoring two touchdowns. The Steagles weren't in first place anymore. The standings now read: