Last Team Standing (32 page)

Read Last Team Standing Online

Authors: Matthew Algeo

It didn't take Baugh long to silence the boobirds. On the very next play he threw a touchdown pass to Joe Aguirre.

With the final seconds ticking down and the Redskins trailing 27-14, Baugh tossed a long pass to Andy Farkas around the Steagles five. Ernie Steele, playing defensive back for the Steagles, intentionally let Farkas catch the ball, then tackled him.

“I knew if I batted down the pass, that would stop the clock,” explained Steele, who lay on top of Farkas until the hands of the giant Longines clock in right-centerfield finally came to rest on zero. Linesman Charley Berry fired his starter pistol and the game was over.

It was the Redskins' first loss in more than a year, and their first at the hands of a team from Philadelphia or Pittsburgh since 1937. It was by far the biggest upset of the season. The

Inquirer

called it an “almost unbelievable” win for the Steagles. Once again it was the line that made the difference: the Steagles outrushed the Redskins 297-58. Jack Hinkle alone rushed for 117 yards, moving him into second place among the league leaders. Johnny Butler rushed for 36, good enough to maintain fourth place. It wasn't the flawless performance that Greasy Neale had hoped for: the Steagles fumbled four times, and Roy Zimmerman was far from perfect, completing just four of ten passes for 44 yards and no touchdowns. But Zimmerman, who played all but five minutes, managed the offense brilliantly and played stellar defense as well. Late in the game, as Sammy Baugh was leaving the field, Zimmerman had rushed over to shake his hand. It was a gracious gesture by the former pupil who, on this day at least, had bested the master, and the crowd applauded appreciatively.

“It was the happiest day of my life,” Zimmerman said after the game, just as Merrell Whittlesey had predicted he would. Zimmerman added that he “didn't have any grudge against the swell guys on the Redskins, but I got even with one man”âGeorge Preston Marshall.

The Redskins did even the score on one count: the body count. This time it was the Steagles who took a beating. Johnny Butler's thumb was broken when a Redskin stepped on his hand. Tony Bova lost two teeth. Bobby Thurbon's lower lip was busted open, and four stitches were required to mend it. Ray Graves, of course, had very sore ribs. Winning, however, was a potent balm.

“What a ball game!” exulted Bert Bell the day after. Looking ahead to the season finale against Green Bay the following

Sunday at Shibe Park, Bell admitted it wouldn't be easy to stop the Packers' star receiver, Don Hutson.

“Still,” Bell said, “we stopped Baugh. Maybe we can pull up with the answer for Hutsonâ¦. Be a funny thing, wouldn't it, if we would stop Hutson and knock off Green Bay Sunday and the Giants could beat Washington twice and let the Steagles tie for the Eastern title. It would be a very funny thing. That George Marshall would be fit to be tied. I would love to see that. I sure would.”

The Giants had stayed in the race by defeating the Dodgers at the Polo Grounds, 24-7. Rookie Bill Paschal, who was coming on strong late in the season, scored two touchdowns for the Giants and rushed for 69 yards, moving him into tenth place among the leading rushers.

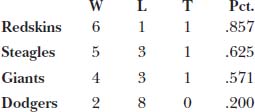

The Eastern Division standings were in turmoil. Since the Giants still had to play the Redskins twice, there was now the possibility of a three-way tie for first, if the Steagles beat the Packers and the Giants took both games from the Redskins. That would force the first three-team playoff in league history. Just about all that was certain was that the eventual winner of the division would meet the Bears in the championship game. The Bears had clinched the West by beating the Cardinals, 35-24. Now things were getting interesting:

After the Redskins game, an ecstatic Lex Thompson once again treated the team to dinner. And, since Washington observed “meatless Sundays,” lobster was once again on the menu. Afterwards the celebration continued in the lounge of the Willard

Hotel, where Greasy Neale granted the entire squad permission to imbibe, which they did liberally. It was quite a party.

“I celebrated a little too much after the game,” remembered tackle Ted Doyle. “I had to catch a train out of Washington [that night] and I went to sleep and missed my train!” He showed up late at the Westinghouse plant the next day, but his bosses went easy on him.

“By then they understood it all. I'd made enough trips. I got off the train in East Pittsburgh and went to work.”

T

HE

R

EDSKINS AND THE

G

IANTS

weren't originally supposed to meet on consecutive weekends at the end of the season. When the schedule was finally hammered out after long and tedious negotiations among the owners in June, the two teams were slated to open the season against each other in Washington on October 3. What George Preston Marshall didn't realize was that Griffith Stadium was already booked on that date: The Washington Senators were playing their season finale against the Detroit Tigers. The Polo Grounds was also booked, as was Municipal Stadium in Baltimore. Lacking other options, Marshall petitioned Commissioner Elmer Layden to reschedule the game to December 12, a week after the other six clubs had already completed their schedules, and only a week after the Redskins and Giants were scheduled to play in New York. It was also the date on which the championship game had been scheduled. Reluctantly Layden acquiesced. The title game was pushed back one week to December 19, which elicited howls of protest from sportswriters who felt the season was already much too long.

“An eight-team organization should be able to complete a forty-game schedule by the first Sunday in December,” wrote Dale Stafford in the

Detroit Free Press.

The Redskins needed only a win or a tie in either game against the Giants to clinch the Eastern Division. If they lost both games, however, a playoff would be needed to crown a winner. And if the Steagles ended their season with a win over Green Bay, the playoff would involve three teams, necessitating a round-robin

format that could push the championship game all the way back to January 9.

So, on December 5 at the Polo Grounds, the Redskins and Giants began what was essentially a two-game series for the Eastern title, with the Steagles a very interested third party. The Redskins were 14-point favorites, and at first it looked like they would take care of business without much ado. They took a 3-0 lead in the first quarter when a “horribly wobbly, half-scuffed” kick by Bob Masterson somehow managed to clear the crossbar from 26 yards out. They made it 10-0 six minutes into the third quarter when Andy Farkas capped a 64-yard drive with a one-yard plunge. But with Bill Paschal leading the way, the Giants came roaring back. The flashy rookie scored on a one-yard run late in the third quarter to cut Washington's lead to 10-7. Then, with less than five minutes left in the game, Paschal brought the crowd of 51,308 to its feet with an electrifying 53-yard touchdown run, which Rud Rennie described in the next day's

New York Herald Tribune:

“[T]he Giants opened the right side of the Redskins' line and Paschal went careening through, into the clear, with only Baugh chasing him. For a fraction of a moment Baugh kept pace. But Paschal turned on the steam and ran away from him, winning the game in 10:42 of the quarter.”

The final score was Giants 14, Redskins 10. Paschal finished the day with 188 yards rushing, the best single-game performance in the league all season. The Redskins had now lost two straight games in which they could have clinched the Eastern Division. In the

Washington Post,

Merrell Whittlesey said their title hopes had reached “the panicky stage.”

A week later, on December 12, in the game that should have been played on October 3, the Redskins' title hopes reached the terminal stage. The Giants defeated them again, 31-7, at Griffith Stadium before 35,540 disgruntled and disbelieving fans, many of whom exited the ballpark in disgust long before the final gun. Bill Paschal had another outstanding day, rushing for 92 yards. That gave him 572 for the season, of which 280ânearly halfâwere accrued in the final two games. It was the first time the Redskins

had lost three consecutive games since 1937. In New York, Giants head coach Steve Owen was hailed as a genius for guiding a club that at one point in the season was 2-3-1 into a playoff for the divisional title. In Washington, there was only angst. The heading over the box score in the

Washington Evening Star

the next day read, “Giants vs. Pygmies.”

The Redskins and the Giants had finished the season with identical records of 6-3-1. A playoff would be needed to determine the Eastern Division champion. But would it include the Steagles? That depended on what the Steagles had done a week earlier, in their final regular season game.

13

13 Win and In

Win and InO

N

S

UNDAY,

D

ECEMBER

5, 1943, the Steagles arrived at Shibe Park around noon, two hours before the kickoff of their game against the Green Bay Packers. Inside the home team locker room, a cramped and damp concrete cube underneath the first base stands, they changed into their football attire, like knights donning armor: pants, cleats, shoulder pads, and, finally, the kelly green jersey, its many tears and rips meticulously repaired by equipment manager cum trainer Fred Schubach. They dressed in silence. The only sound in the locker room was that of white athletic tape being ripped from its spool to stabilize creaky joints and bind aching muscles. The players' bodies were worn out, not only by the punishing football season, but also by the long hours they put in at their war jobs. They were weary, yes, but they were also excited. For most of them this was to be the most important football game they had ever played, certainly professionally.

It was remarkable that they had gotten even this far. Thrown together by necessity and chance, they were a motley bunch, the unwanted remnants of two mediocre teams, with a host of ailments: ulcers, perforated eardrums, trick knees. There had been animosities, but they had been overcome, and now they were truly a team, a team on the verge of a championship no less.

“When you're on a team,” explained center Ray Graves, “you're part of the team whether you like it or not. You can have fights among yourselves, but you're still a team. That's the way football is.”

Once in uniform, the players went out to the field to warm up, stretch, do calisthenics, run a few drills, and check out the condition of the turf, which by this point in the season resembled a bombing range. They were surprised by how many people were already in the stands.

Around 1:15 p.m., Greasy Neale and Walt Kiesling called the team together in the locker room. The 25 players took seats on the long benches that ran in front of the lockers on three sides of the room. They were “wound up and ready to fight.” Don't worry about what the Giants and Redskins are doing up in New York, the coaches told them. Just do your job. There were no hysterical, hyperbolic speeches, no spittle-emitting harangues or tear-jerking pep talks. Neither coach was like that.

“There was never any idle talk,” Vic Sears said of Greasy Neale. “It just never occurred to him to waste any time.” Ted Doyle said Kiesling wasn't a “fire-'em-up” kind of coach either: “He just pointed out some of the things you should do and some of the things you shouldn't, that type of thing. In fact, there weren't many people that were fire-'em-up in the league then.”