Legio XVII: Roman Legion at War (5 page)

Read Legio XVII: Roman Legion at War Online

Authors: Thomas A. Timmes

gladius

[sword] and shield, they often talked about the barracks’ rumors that had them deploying to fight in Sicily in conjunction with the Navy’s attempt to defeat the Carthaginian Navy.

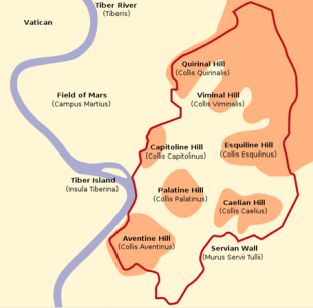

Figure 2 Campus Martius

Figure 2 Campus MartiusHowever, before the recruits could graduate, the 23 year old First Punic War ended in a decisive victory. The Carthaginians lost their fleet to the new and powerful Roman Navy. They also lost their possessions in Sicily, known as the bread basket of the Mediterranean, and the island of Sardinia. Carthage also agreed to pay Rome an enormous indemnity to cover the cost of building the same Roman fleet that had just defeated them.

A month after the 1

st

Punic War ended, in April 242 BC, Manius’ class of Roman recruits graduated from basic training. Manius was selected by his peers and Training Centurions as Best Recruit of the Class and received an iron

gladius

with his name emblazoned on the edge. He was bursting with pride as he slid the weapon into its scabbard. He was finally a legionaire and had achieved his boyhood dream. He now wanted to test himself in actual combat as his brother had, but the war with Carthage was over. He feared he missed his only chance to prove himself by a matter of mere months.

Most of the Legions mustered in for the war with Carthage were disbanded. Only six were retained to maintain order throughout the Italian peninsula and to stand ready should the Gauls of northern Italy once again attempt to invade central Italy as they had done successfully in 387 BC.

It was hard for young Manius to imagine that 145 years ago, Rome was so weak that the

Senoni

, a Gallic tribe from northern Italy led by Brennus, actually defeated six legions at Allia, a mere 11 miles from Rome, then sacked the city and were even paid an indemnity. He angrily vowed that that same ignominy would not happen again while he was in the army.

At the end of the 1st Punic War, the Carthaginian Ambassador to Rome and chief negotiator to handle end of war settlements was an odd fellow by the name of Davood Farrid. He was a 26 year old effete Persian with the quixotic mission to minimize the impact of the wartime defeat on Carthage. He was known,

inter alia

, for his boring screeds on tolerance, forgiveness, and compromise. Roman negotiators wondered how he managed to lift, must less point, his bony ring encrusted fingers at the maps and scrolls that defined the magnitude of the Carthaginian humiliation. He attracted derision like cow dung draws flies and would temporize over every settlement issue. His delaying tactic and utter pathos tended to wear down his counterparts into greater and greater compromise.

Counter intuitively, his gaudy outward appearance and foppish behavior generally fooled most into believing he was an absolute simpleton and needed help to avoid execution upon his return to Carthage. But in reality, his skill lay in actually getting people to like him despite their better judgment and to feel exceeding sorry for him and to want to help him. It was a ridiculous strategy, but for a spy in the open, it worked. That is, on all but Levi, who viewed Davood as treacherous and not to be trusted.

Levi and Farrid were about the same age. They first met while the war was winding down and took an instant dislike to each other. Perhaps it was memories of events long since passed that caused this mutual animosity or maybe it was caused by Farrid’s shock at discovering a Jew in Rome. Before the two stopped speaking altogether, Farrid explained to Levi that his Persian ancestors moved from Persia to Judea in 539 BC when Cyrus II, better known as Cyrus the Great, conquered the Babylonian Empire and freed the Jews from their 70 years of exile in Babylon. Farrid’s ancestors returned with the Jews to Israel and confiscated the lands and property of those Jews who elected to remain in Babylon. Farrid explained that a great amount of wealth was expended in making the land prosperous again and establishing standards suitable for Persian tastes.

Farrid said that there was always some lingering animosity between the Jews and their new wealthy Persian neighbor. However, there was no violence for the next 270 years. Eventually, Hellenization and its accompanying intolerance for things Jewish caused conservative Jews to finally rise up in revolt and expel foreigners from Israel, including Farrid’s family. Interestingly, this same Hellenization and whole scale rejection of Judaism caused Levi’s parents to set sail for Corinth and religious freedom.

The ejected Farrids were now without a country, but were by no means destitute. They immediately sought a new life in Carthage. Their contribution to this growing economic powerhouse resulted in the appointment of Davood as Ambassador to Rome. As is customary in that part of the world, Davood never forgot how the Jews treated his ancestors. This memory generated an ingrained and long lasting attitude of hatred and desire for retribution against all things Jewish. Levi immediately became the target of his acerbic tongue and nefarious intrigues.

Ambassador Farrid remained in Rome for about a year after negotiating a settlement to the war and then returned to Carthage. He remained Carthage’s permanent Ambassador to Rome and for the next 23 years of relative peace spent his time meddling in both capital cities despite the fact that he detested the inevitable sea sickness that accompanied each crossing of the Mediterranean.

Much to Manius’ great disappointment, the next 17 years were years of relative peace for the Roman Republic. His earlier fear that he had missed his one chance to actually fight in a big battle was proving to be quite accurate. Carthage was quiet, but there were consistent rumors that another war with them was inevitable. The scattered tribes throughout the Italian peninsula were always in a state of insurrection, but were easily subdued by a show of force. Like Carthage, the Cisalpine Gauls in northern Italy were quiet for now, but always dangerous and unpredictable. They were a fiercely independent people and vigorously resisted Roman interference or domination.

His service with the Army had taken him and his brother to every corner of Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, and several Greek Islands aboard the Navy’s quinqueremes. He enjoyed all his assignments except those that involved traveling on water. At first, the idea of being rowed across the

Mar Nostrum

[Mediterranean] seemed like an exciting adventure, but quickly turned sour when the ships hit the open water. Like many of his comrades, he was sea sick for the entire voyage and vowed that he would do whatever it took to avoid a similar experience. He also served under a few Centurions who were brutal in their treatment of minor infractions. He did his utmost to steer clear of these men and vowed not to duplicate their mistreatment of Legionaries should he ever become a

Centurio

[Centurion].

Like his brother, he rose through the ranks and attained the vaunted position of Centurion and eventually Military

Tribunus

[Tribune], a senior Legion officer, [equivalent to a Brigadier General]. His demonstrated leadership and bravery were undeniable, but it was his ability to think and plan that caught the eye of superiors. He was known to remain calm in the midst of chaos and was always mentally two steps ahead of his adversaries. Because of his Plebian status, however, Manius knew he could never command a Legion. That was the job of the Legates (Legion Commanders), as well as the two elected Consuls, Provincial Proconsuls, and

Praetors

most of which were drawn from the Patrician class.

In 225 BC, Manius was 34 years old, unmarried, and had served in three different legions over his 17 years in the army. Six years earlier in 231 BC, he had been elected a junior

Hastati

Centurion [

Hastati

is the first of three lines of a single Legion facing the enemy] and this year was appointed a Senior

Principes

Centurion [second of three lines of a Legion facing the enemy] by the Legate for his ability to lead and motivate troops.

Legionaries were required to serve for six years in the Army, but could stay on and retire at age 35 with 18 years’ service if they so chose. Manius was undecided at this point whether to continue the work he knew and at which he excelled or retire and become a fisherman like his father. The fisherman desire was really an unrealistic escapism fantasy, but he would think of it often. Within the year, circumstances beyond his control would decide the matter for him.

[Typical Roman Legion: A Centurion [U.S. Army Captain] commanded 1 of the 10 Maniples that comprised each of the three battle lines of a Legion:

Hastati

,

Principes

, and

Triarii

. The three battle lines were called

Triplex Acies

or “triple battle order.”]

Depending on the number of sick soldiers or those otherwise unavailable for duty on any particular day, a Maniple comprised 160 men [U.S. Army Infantry Company]. The Centurion was responsible for everything the Maniple did or failed to do. During the attack, his fighting position was to the right of the first man in the first row. Many a Centurion died while leading thus from the front, but it was necessary for his men to be able see and hear him during battle.

The Legions had recently undergone a reorganization and Manius preferred it over the previous one. The older formations were comprised of 60-man Maniples with 15 Maniples assigned to the

Hastati

and

Principes

for a total of 1,800 men, and 45 Maniples for the

Triarii

. These Legions totaled 4,500 men each while the new Legions totaled 5,500.

Despite his good intentions, Manius treated the men roughly. He saw them as mere farm boys who needed to be bullied and driven like plow horses. He could tell the men feared him, which he liked, but they also despised him, which he did not like. Over time, his abusive attitude changed. He developed a need to be appreciated for his talents and he wanted simple companionship. Manius began to view his Legionaries as young men who wanted to do the right thing and just needed good leadership. He began to care more about their health, comfort, level of training, and general wellbeing. He was mindful they were citizens performing their required service. In return, the soldiers were loyal to Manius and obeyed his commands without hesitation. Unlike many other Centurions, Manius could no longer bring himself to employ harsh discipline when correcting troops. Usually, just knowing that they had disappointed him was punishment enough.

He often agonized over ways to lighten the 66 pound load Legionaries carried while on campaign, but without success. The necessity for food, animal fodder, fuel, and fortifications could not be ignored. Body armor, weapons, shield, food rations, water, shovel, two palisade stakes, a saw, pickaxe, sickle, rope, wicker basket, extra clothes, and kitchen utensils all added to the painful weight each soldier was required to carry. Thankfully, pack animals carried the common items such as bulk food, leather tents, and spare equipment. Manius often encouraged his soldiers to brainstorm ways to improve their individual lives and their equipment, and was able to use many of their ideas in one of his later Army assignments.

Manius was paid 75

As

[10

As

bronze coins are worth US $21] when he enlisted and then earned another 1

As

per day. Thirty-five

As

were subtracted each year for food, equipment, and taxes, which left him 330 for the entire year. Rather than spend it all each month, Manius always managed to send his mother 60

As

a year. When he was promoted to Centurion, his pay jumped five times to 1825

As

[$3822] a year. He felt like a rich man and still managed to save some of it.