Legio XVII: Roman Legion at War (7 page)

Read Legio XVII: Roman Legion at War Online

Authors: Thomas A. Timmes

Figure 5 Apennines Mountains

Figure 5 Apennines MountainsThe Gallic cavalry that spotted Regulus’ landing at Leghorn also observed the two Roman Legions now marching up the

Via Flaminia

, and the three Auxiliary Legions going north on the

Via Aurelia

. Riders galloped back to report the news, which prompted an immediate change of plans for the Gallic Army. Wishing to avoid an encounter with Papus’ heavy Roman Legions that were now marching to confront them, the Gauls abandoned the east coast and marched rapidly through the central passes of the Apennines Mountains and emerged into Tuscany on the west coast. They were now on a collision course with the Auxiliaries.

Always greedy for loot, the Gauls plundered and burned the villages as they went. They got as far as

Clusium

[Chiusi] only 100 miles north of Rome when they were suddenly brought face to face with the three Auxiliary Legions in battle formation. The Gauls were completely surprised. The Gallic chieftains were outraged that their cavalry had failed to detect the rapidly moving Auxiliaries.

Not wanting to fight the Auxiliaries where they could get trapped between four Roman Legions coming to their aid from the east and the west, the Gauls traveled north away from Rome. They march 80 miles in five days hoping to shake the pursuing Auxiliaries and finally stopped at

Fluentia

[Florence]. On several occasions, the Gallic cavalry attempted to block the Auxiliaries pursuit, but without success. The head strong

Praetor

was determined to fight and relentlessly pushed his untrained troops to catch the fleeing Gauls.

When word was brought to Consul Papus that the Gauls were in a headlong retreat northward from Chiusi to Florence with the Auxiliary Legions in pursuit, he immediately sensed disaster and ordered his now five Legions (the 15,000 veterans had joined him) to force march across the Apennines Mountains to support the

Praetor

. He also dispatched riders to order the Auxiliary Legions

to immediately break off the pursuit and await his arrival. These orders arrived too late. Similarly, messages sent to Regulus instructing him to break camp at Pisa and march with all haste the 68 miles south to aid the Auxiliaries, did not arrive in time.

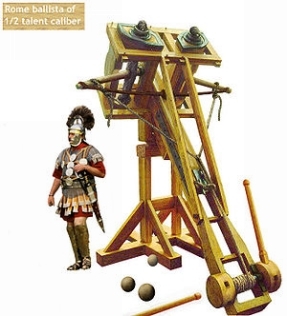

Figure 5

Ballista

By now, the Gauls had a good fix on the locations of the two Consuls’ seven Legions and realized that they were too far away to support the Auxiliaries. Concolitanus and Aneroestes picked the village of

Faesulae

[modern Fiesole, about two miles NE of Florence] as the place to fight the Auxiliaries. They sensed an easy victory and they were correct.

The Gauls prepared an ambush and other surprises for the

Praetor’s

army. The Gauls dug in on a slight rise behind a 8’ wide 6’ deep ditch. Large Gallic infantry formations were hidden out of sight in woods and ravines on the two flanks. Their new

ballistae

were positioned on a hill overlooking the battlefield in a perfect position to hurl their huge 9’ shafts over the heads of their men and into the charging Auxiliary ranks.

[The

ballista

was originally a Greek weapon mounted on city walls to fire down into attacking enemy infantry or into their siege weapons. It was ungainly and could only be moved from one location to another with great effort. Roman engineers and blacksmiths were in the process of adapting the

ballista

for mobile field operations, but had not yet perfected it. Somehow the Gauls beat them to it and were about to unleash its power on the hapless Auxiliaries.]

The Battle of

Faesulae

225 BC

Marcellus’ mounted scouts found the Gauls drawn up in battle lines on a slight hill. They failed to spot the heavy infantry hidden in the woods on the flanks or the

ballistae

on the hill. When the

Praetor

heard the report, he rushed his three Legions into battle. He felt confident. He had been chasing the Gauls for five days and now that he had finally caught them, he planned to bring the operation to a rapid and successful conclusion.

Marcellus was not given to seeking glory, but was aware that by destroying this threat to Rome, he would receive honors and rewards. With those thoughts, he ordered the three Legions into the

triplex acies

battle formation with Legions abreast. However, rather than advance in the customary checkered board pattern with staggered Maniple, he had the

Hastati

of the two Legions form a solid shield wall of 1500 men with two men lined up behind each lead man. He kept the staggered checkered board pattern for the

Principes

in case the

Hastati

needed to fall back and get behind the

Principes

to rest or regroup.

The one long

Hastati

line advanced in good order over the broken ground. They stretched out over half a mile in width and were about 6’ deep. The men sensed victory since they knew that they could over power the few Gauls they could see. The Centurions worked hard to keep them from breaking into a running charge. The

Principes

and

Triarii

followed closely behind the

Hastati

. Spirits were high.

When the lines were about 60 yards apart, the Gauls unleashed their five

ballistae

. The results were devastating. Each shot found a target. Three to four men were impacted by each

ballista

arrow as they penetrated shield, armor, and flesh, and still keep going! At the same time, skilled Gallic bowman began to fire their arrows in rapid succession. Falling men and exploding equipment opened gaps in the lines, which were not closed by these untrained troops. The line hesitated as men sought refuge by squatting down behind their shield or lying flat on the ground. The veteran Centurions ran among the ranks pushing and prodding the troops to get up and continue the attack, but most suffered the Centurions blows and stayed put.

As the

ballistae

and bowmen’s arrows continued to smash into the stalled

Hastati

ranks, the inexperienced

Praetor

attempted to pass the

Principes

, another 5000 men, through the

Hastati

to continue the attack. It was total chaos. The ranks became horribly intermingled with troops bunched up and not even knowing which way to face. Confusion reigned supreme. Concolitanus and Aneroestes sensed this was the moment to call the hidden warriors out of the woods and ravines to hit the milling Auxiliaries on both flanks. They also ordered the troops on the hill to jump over their now unneeded ditch, reform themselves, and attack downhill on the run.

To the Auxiliaries’ credit, those that remained on the field put up a valiant fight. Many others deserted for the woods at a dead run, but most fought in the general melee as the Gauls smashed into the flanks and head of the Auxiliaries formation. The strong Gallic cavalry circled around behind the doomed men and pinned the third line, the

Triarii

, to prevent them from attempting to take the pressure off the first two ranks.

In the end, the remnant, the

Triarii

, about 6000 of the most experienced Auxiliaries evaded the harassing Gallic cavalry by listening to their leaders, keeping their formation, and moving rapidly away from the victorious Gauls onto a wooded hill for a last stand. The main battle was over very quickly and it was a slaughter. Over 8,000 Auxiliaries were killed or captured. Marcellus was captured, nailed to a tree, and skewered with spears. The Gauls lost a mere 300 men. Rome had suffered a humiliating and devastating loss. Furthermore, this Gallic victory could embolden other tribes in the Cisalpine to try the same thing for the promise of loot, prestige, and freedom from Roman interference.

*******

After an exhausting 100 mile six-day forced march across the Apennines, Papus and his five Legions arrived at

Faesulae

from the east on the evening of the battle. They saw the shattered Auxiliary army lying in the field, but could not stop to inspect the carnage. It was late in the day and the Legions needed at least two hours to prepare their fortified camp for the night. The stranded

Triarii

was instructed to dig in on the hill and wait for daylight. Papus feared the emboldened Gauls might attempt a night attack against his position and posted extra security. He knew his troops needed to rest, but overall camp security was paramount. The night passed without incident. The Gauls, too, were exhausted after marching for five days, preparing defensive positions, and fighting a three hour battle. Everyone slept.

*******

Regulus’ two Legions arrived from Pisa around noon of the following day and joined the surviving

Triarii

on the hill. Regulus further fortified the hill. The men dug ramparts and ditches and added sharpened stakes to create obstacles. Regulus used the survivors from the

Triarii

to form a reserve Legion, but was well aware that they were spent physically and mentally. Their morale was shattered and he felt he could not rely on them.

The mercenaries Concolitanus and Aneroestes were in no mood to fight another Roman army so soon. Their men needed a rest. But they were not ready to quit the field quite yet. His men were burdened down by loot from months of scouring towns and villages and were fearful that they could lose it all if the Romans won the next battle. Their allied tribesmen, the

Insubres

and

Boii

, were beginning to talk of going home. They were tough fighters, but they were also farmers and could not remain absent too long.

Nonetheless, the two Gallic leaders decided to risk it all and attempt an attack on Rome itself or at least the rich suburbs. There would never be a better time. Morale among the troops was high and they had just decisively defeated a sizable enemy force. They felt that given the proper conditions, the army could even take on and defeat multiple Roman Legions. The decision was made to gamble it all and move south to Rome.

*******

Both Roman Consuls were extremely leery of fighting the Gauls other than on very favorable terrain where they would have an advantage. They could see and were beginning to smell the results of the Auxiliaries’ ill conceived plan of battle. Once the Gauls abandoned the battlefield, the Romans took possession. The Gallic camp was about a mile from the battlefield and situated between the city of Rome and the Legions. Regulus and Papus were separated by 400 yards of woods and fields and about that far from the battlefield.

Regulus assumed command of the combined Roman Army of seven Legions and ordered Papus not to engage the Gauls until the entire Army could unite and find more favorable terrain. The Romans stayed put in their well fortified camps to await the Gauls next move. Would the Gauls go north back to the Cisalpine or south to Rome? If Rome was the target, then the Legions were in the wrong place to block them. They needed to get the fighting Legions between the city and the Gauls.

Meanwhile, teams of experienced Tribunes and Centurions were sent from the two Roman camps to inspect the battlefield. Manius was one of the ones chosen. He hoped his brother had made it to the hill with the

Triarii

, but knew he was with the

Principes

and feared the worst.

Manius walked among the dead. He had never before seen death on such a vast scale. He was repelled by what he saw, but could not take his eyes off the devastation. Every manner of injury was lying before him: missing limbs, heads, horrific gashes, impalements, and arrows and spear wounds. There was blood, entrails, and body parts scattered everywhere. As he continued to walk and look, he noticed that many of the Roman shields had deep slashes cut into their tops and the helmets of the men holding those shields were also split in two. He could see that the heavy Gallic slashing sword when swung overhead easily cut through the shield and helmet. He would mention this to the Legate.

As he entered deeper into the slaughter stepping carefully to avoid the dead, the Gauls left no wounded, he saw his brother. He was face up and covered with dried blood. Manius stood there and looked. He felt his throat tighten and his eyes filled with tears. Like so many others, Gaius’ shield had been cut and his helmet split. As he bent down and gently removed the helmet from his dead brother’s head, memories of the two playing as children in the river flooded his mind. He silently wept for his brother and for their youth. He thought of his dead father and still living mother. She would have to be told. He touched his brother’s cheek as a farewell gesture, tucked Gaius’ helmet under his arm, and walked on. This was death and life for a Legionaire. He had a job to do and would mourn later.

Manius spotted a group of Tribunes and Centurions talking excitedly and huddled around a clump of bodies. When he joined the group, they made way for him and pointed to a 9’ long 4” thick pole that had impaled three soldiers. The pole had penetrated the first man’s shield and chest, the second man’s chest, and the third man’s groin. The iron tip of the pole was clearly visible as it extended out the back of the man’s leg. He had evidently bled to death struggling to break free of the barbs. Manius shivered when he realized that this was a

ballista

arrow fired by the Gauls. One of the Tribunes spotted another

ballista

impact, then another, and another. As the group turned and surveyed the battlefield, they spotted numerous

ballistae

strikes.