Legio XVII: Roman Legion at War (11 page)

Read Legio XVII: Roman Legion at War Online

Authors: Thomas A. Timmes

This was totally unexpected and, therefore, peaked everyone’s’ interest. They eventually discovered that the size of the wings and angle of their tilt determined its range and angle of flight. The arrow could be made to either dive into the ground or soar upwards. They also discovered that by imbedding lead weights into the shaft of the arrow, it had a much greater penetrating power albeit a shorter range. The bottom line for Manius was that the wings would increase the normal

ballista

range of 400 yards by about 200 yards. Further effort on the project was abandoned for the moment, but Manius would return to it.

The Army Board accepted the modifications and the new equipment was issued to the Legions. Manius had grown in sophistication and practical wisdom during this entire process and impressed all with whom he came into contact. Levi was so pleased with the results of Manius’ effort that he recommended him for promotion to Military Tribune. The

Concilium Plebis

concurred and Manius became Tribune Manius Titurius Tullus [a Brigadier General].

His pay had gone from 1

As

per day as a common soldier to 5

As

per day as a Centurion to 6.5 as a Tribune. When he told Lucia that he had been promoted, she quickly calculated that their pay would jump from their Centurion’s pay of 1825

As

per year to 2380 [$5000].

Clastidium

222 BC (6 years before

Cannae

)

Now that Tribune

Tullus had completed his three year assignment with Levi to improve the Army’s equipment, he immediately requested an assignment with a Legion, but not to just any of the six currently in the field. He specifically asked to be assigned to one of the two Legions commanded by four-time Consul and highly experienced soldier Marcus Claudius Marcellus.

Marcellus was raised with the purpose of entering military service. He quickly distinguished himself as an ambitious warrior, who was known for his skill in hand-to-hand combat. He is noted for saving the life of his brother, Otacilius, when the two were surrounded by enemy soldiers.

As a young man in the Roman army, Marcellus rapidly rose through the ranks. For his exceptional service, in 226 BC he was appointed

curule aedile

of the Roman Republic. An

aedile

was an overseer of public buildings and festivals and an enforcer of public order. This is generally the first position one seeks when desiring a political career. The title of

curule

signifies that the person is a patrician, or upper classman, rather than a plebeian, or commoner as was Marcellus. Around the same time that he became an

aedile

, Marcellus was also awarded the position of

augur

, an interpreter of omens.

By the age of 46, in 222 BC, Marcellus was elected to serve as one of the two Consul of the Roman Republic, the highest political office and military position in Rome. The second Consul was also an experienced soldier by the name of Publius Cornelius Scipio. Consul Scipio’s father was Lucius Cornelius Scipio, himself a well known Consul, Censor, and General of the victorious Roman fleet during the 1st Punic War.

The Scipio family was one of the oldest and most widely respected of the six major patrician families in Rome. [Consul Scipio’s brother was also a Consul who was killed in 211 BC during the 2nd Punic War. This Scipio was the father of the most famous Scipio of all, Scipio Africanus, 235-183 BC, who was a Roman Consul, survivor of

Cannae

, and the General who finally defeated Hannibal in the battle of Zama in 202 BC.]

Consul Marcellus had a reputation as an exceptionally detailed planner and one who could conceptualize an entire campaign before it happened. Rumors abounded that he drove his subordinates to the point of exhaustion and treated the ordinary troops a bit too harshly. Nonetheless, Manius felt Marcellus had much to teach him and looked forward to campaigning with him.

Marcellus reviewed Tribune Manius’ application to serve with him and was pleased to grant his request. Manius had already acquired a reputation as a loyal, intelligent, and experienced soldier. Marcellus appointed him as Senior Tribune for Maneuver and Operations of the two assigned Legions. Manius was junior to the two Legates who commanded the Legions, but since Manius spoke for the Consul in matters of maneuver and operations, he wielded considerable authority. Manius viewed his appointment as a unique learning opportunity and totally committed himself.

After the Battle of

Telamon,

three years earlier, Roman spies in the Cisalpine Gaul began to report that the Gallic

Insubres

and the non-Gallic

Ligures

along with the

Boii

and

Gaesatae

had established a fort at

Acerrae

alongside the River

Addua

[Adda]. This fort was close to where the

Addua

joins the

Podus

[Po] River, which is a major east-west river and vital for Roman commerce. The

Insubres

built the fort at

Acerrae

[modern Pizzighettone/Gera)] and used the fort to extract taxes and goods from Roman and non-Roman river traffic.

The

Abdua

is a tributary of the Po. It rises in the Alps near the border with Switzerland, flows through Lake Como, passes by the fort at

Acerrae

, and joins the much larger Po. The fort is about seven miles upstream from the confluence of the two rivers.

Another reason for Rome’s interest in the fort at

Acerrae

was that the Roman supply fort at

Clastidium

[modern Casteggio] was a mere 50 miles to the west. The supply fort was also situated 30 miles south of and precariously close to the

Insubres

capital of

Mediolanum

[Milan].

Clastidium

was established to collect, store, and eventually ship to Rome various trade goods such as grain and metal ore gathered from the several Gallic and non-Gallic tribes in the Cisalpine. The relationship worked fairly well and required a relatively small garrison to defend. The fort at

Clastidium

was built to defend against a weak opponent. After all, the local Gallic population benefited from the fort as much, if not more so, than did the Romans. An attack was always possible, but considered remote.

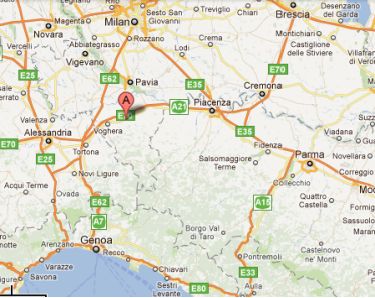

Figure 7 Clastidium (Google Maps)

Figure 7 Clastidium (Google Maps)This thinking, however, changed with the establishment of the fort at

Acerrae

and the resultant Gallic interference with commerce on the rivers. Strong enemy forces were now an easy three to five days march away from

Clastidium

and in direct competition for trading goods. The Roman Senate and the

Comitia Centuriata

studied the problem, weighed the options, and concluded that as long as

Acerrae

stood, it posed a continual threat to Rome’s interests in the Cisalpine.

Acerrae

had to be removed either peaceably or by force.

There was another unspoken yet powerful motivator for the

Comitia Centuriata

to vote to go to war over

Acerrae

. Ever since the city of Rome was invaded 165 years ago by these wild, undisciplined and frightening Gallic men from the north, a deep fear of them had been embedded into Roman culture and psyche. To the average Roman, they represented the dark brooding malevolent evil of childhood fantasy that refused to simply go away upon waking or growing up. It was a very real threat and was at the core of Roman decision making. This fear was fueled, in part, by the simple fact that the average Gallic male stood two to three inches taller than the average Roman and elicited an unspoken Roman insecurity.

The two Consuls were each assigned two Legions and instructed to march without delay to “disestablish” the fort at

Acerrae

by any means necessary. They were also instructed to strengthen the fortifications at

Clastidium

and to send a message throughout the Cisalpine that Rome would not tolerate any interference with her trade. The four Legions began the process of assembling the necessary food, fodder, and fuel to sustain them for at least 6-months in the field.

As the senior Consul, Marcellus was given the honor of planning the campaign, but Scipio retained the right to veto any aspect of the plan. This was standard procedure and ensured full cooperation between the two Consuls.

Marcellus gathered a few trusted former Consuls, former and sitting Senators, and the four Legates, as well as several experienced soldiers, including Manius, to brainstorm a concept of operations. The Legions meanwhile made preparations to deploy.

After three full days of non-stop discussion and planning, Marcellus directed his staff to assemble the 24 Tribunes from the four Legions, 60 Centurions (15 from each Legion), and 80 ordinary Legionaries (20 from each Legion). This was 100% Marcellus. After he had already thought his way through the upcoming campaign, he would assemble the key players involved in the operation and brief them. Afterwards, he would request input from the assembly, but rarely received any since his thinking was so detailed and complete.

On the appointed day, Marcellus rose, faced the audience, surveyed the faces, nodded to a few, and began to speak. At first his delivery was slow, precise, and authoritarian, but as he warmed to his topic, he picked up the pace, showed his enthusiasm, and pulled everyone along with his confidence and professionalism. This was a leader that soldiers and civilians alike wanted to follow!

He started by detailing the preparations that were completed or still underway. He knew to the pound the amount of grain, fodder, and fuel the Army would transport; the number of pack animals and weight each would carry; and he knew with precision the history, linage and personnel strength of each of the four Legions. He even knew many of the Centurions by name and the campaigns in which they had participated. His ability to recall facts and data was astounding.

“I expect,” he said, “about 10,000

Insubres

to be in and near the fort at

Acerrae

and another 30,000 to 50,000, which could be mustered against us if the people in the region mobilized, particularly the

Boii

. To pin the

Boii

to their home territory, an Auxiliary force made up of

Umbros, Veneti

, and

Cenomani

under Roman leadership will march up the east coast to the

Boii

territory to keep them in place.”

He reviewed the

Insubres

fighting tactics, body armor, weapons, and concluded with the warning not to underestimate their bravery and fighting skills.

Marcellus said that their Senate-directed mission was to disestablish the fort at

Acerrae

by any means possible, demonstrate the power of Rome to maintain her supply routes, and encourage mutual cooperation with Rome. He said he would try to persuade the

Insubres

to abandon the fort peaceably, but held out little hope for success.

He announced the departure time and march order of the four Legions and their baggage trains on the

Via Aurelia

. “The 3rd Legion and their trains will lead. I will march behind the 3rd Legion along with the command group, 100 cavalry troopers, and 20 mounted couriers. 4th Legion will be next with their baggage, then 5th and finally 6th Legion will provide rear security. Each Legion will also provide 10 empty wagons to follow their Legion in order to pick up those men unable to continue the march. I anticipate approximately 100 men per Legion will suffer debilitating blisters, thigh chaffing, and illness. These men will be returned to duty as soon as they are fit. The cavalry will maintain a 360 degree screen around the Legions with elements 10 hours out from the army to provide early warning.”

His concept of the operation was straight forward. The Army would march approximately 15 miles per day for 23 days and establish a standard encampment each night. Naval ships would screen the coast keeping pace with the march and supply the Army every three days. Cavalry elements would maintain constant contact with the fleet. Ship board Auxiliaries would offload the supplies at predetermined ports and provide escort until it reached the Army in the field.

If attacked enroute, Marcellus said he would select defensible terrain and initially put three Legions on line and hold one in reserve.

Engineers would accompany the cavalry on the

Via Aurelia

to determine the status of the bridges enroute to the target. The Engineers were prepared to reinforce or build new bridges if required. Crossing the Po River will be a major undertaking and require vast resources if the existing bridges are out when the Army arrives. Marcellus directed the cavalry to identify a usable bridge over the Po and hold it secure once the Army approaches the area. The idea was to cross the Po upstream (west) of the joining of the Po and Adda and approach

Acerrae

from the west.

“Once at the fort, I will offer a peaceful resolution to the

Insubres

. If refused, I plan to encircle the fort with a ditch 8’ across, 10’ deep, and 60’ away from the fort. Each Legion will be responsible for a portion of the ditch to man 24 hours a day. Each Legion will dig an encampment opposite one of the four walls of the fort.”

“Should the

Insubres

attempt a breakout at their east facing and only gate, the opposing Legion and two closest would contain them in a half circle. The remaining Legion will assault the west wall opposite their gate to capture the fort or discourage any breakout attempt.”

“While conducting the siege, supplies for the Army will be shipped by sea through the

Ligurian

port of

Genua

[Genoa] and be escorted to

Acerrae

by an onboard Auxiliary Legion mustered in for this purpose.”

Marcellus said he fully expected the

Insubres, Ligures

, and

Boii

to mobilize up to 50,000 men and attack the army at

Acerrae

to break the siege or to attack the Roman supply base at

Clastidium

to pull the Army away from the siege. He then added, “Reinforcements are enroute to

Clastidium

to enable them to hold out for three days. This will allow time for us at

Acerrae

to abandon the siege and go to their rescue. As soon as we leave

Acerrae

, for

Clastidium

, the

Insubres

will probably resupply the fort, but there is no way to prevent it. If a small force were left at the fort to attempt to prevent the resupply, they would be slaughtered by the much larger

Insubres

force.”

“Either we all stay at

Acerrae

or all depart for

Clastidium

. The Army would be ill advised to attempt to split its forces in the face of a larger enemy force.” Manius had vigorously argued this point with Marcellus and won the day. Other advisors wanted to leave a detachment of cavalry and infantry at Acerrae.

Marcellus pointed out that their 22,000 Legionaries would be outnumbered more than 2 to 1 if the worst case scenario unfolds. Nonetheless, he expressed confidence in the outcome. At this point, he extended his gratitude to Manius for the recent equipment upgrades and felt that these changes along with solid Centurion leadership would carry the day.

He concluded his two hour briefing by pointing out that this operation was not a punitive expedition against the

Insubres

or

Liguri

people, but against the fort and its interruption to commerce.

Months earlier, Marcellus witnessed a demonstration on the use of war dogs and was greatly impressed. These

molossus

dogs [mastiff-type] from Epirus Greece were fitted with spiked collars and armor and were utterly fearless. They would attack man or beast on command. Marcellus obtained 20 dogs to accompany his Legions for this operation.

The expedition progressed exactly as Marcellus predicted it would with few minor changes. The four Legions marched north two days later while the Auxiliaries marched east to

Boii

territory. Rough seas only once prevented the off loading of supplies; otherwise the resupply effort went fairly well. The

Insubres

failed to burn any of the three bridges over the Po River and the Army crossed as expected.

Not surprisingly, the

Insubres

declined the offer to surrender the fort and a siege was initiated. Within 10 days, scouts told Marcellus that the

Insubres

,

Ligures

and

Gaesatae

were, indeed, mobilizing their forces and planning to attack

Clastidium

~ exactly as foreseen!