Legions of Rome (61 page)

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

The Caledonians had “reddish hair and long limbs,” said Tacitus, which he felt indicated they were of German origin. [Tac.,

Agr

., 11] There is no mention of painted faces or limbs among the Caledonians at Mons Graupius or during any of Agricola’s seven British campaigns. The first reference in Roman literature to Picts of Scotland—from

pictus

, meaning “colored” or “tattooed”—would not be for another 200 years. The Pict name, and the habit of the warriors of Scotland painting themselves for war, were still a long way off when the tribes of Caledonia assembled to fight Agricola’s army.

“The Britons are unprotected by armor,” said the 1st Tungrian Cohort officer. [

VWT

] Neither did they wear helmets. For weapons, apart from spears, Tacitus says that the Caledonians carried small shields and “unwieldy swords” with rounded ends. [Tac.,

Agr

., 36] While no archaeologist or farmer has to date dug up examples of any especially large Caledonian swords from this period, Tacitus was adamant that the swords used by the Caledonians in this battle were “huge.” [Ibid.]

When Agricola stepped up on to the tribunal in the Roman camp, he estimated that the Caledonian army numbered in excess of 30,000 men. [Tac.,

Agr

., 29] As he addressed his troops, warriors had continued to flood to Mons Graupius, enlarging the Caledonian army even more. The Caledonian numbers seem to have taken Agricola

by surprise. Only later, from prisoners, would he learn that the previous year the tribes had set aside old differences that had them frequently at war with each other. They had sent envoys around the tribes, a treaty had been signed and ratified by sacrificial rites. Then, the men had sent their women and children away to places of safety, and had vowed to band together to fight Rome. [Tac.,

Agr

., 27]

This uniting of the tribes may well have been the work of a Caledonian chieftain by the name of Calgacus, who was the chosen war chief of the tribes, “a man of outstanding valor and nobility,” according to Tacitus. [Tac.,

Agr

., 29] It was later reported to Agricola that Calgacus delivered a stirring speech to the assembled warriors at Mons Graupius, in which he had reportedly said to his countrymen, “Which will you choose? To follow your leader into battle? Or to submit to taxation, labor in the mines, and all the other tribulations of slavery?” The future of the Caledonians would be decided here, on this battlefield, said Calgacus. “On then, into battle! And as you go, think of those who went before you, and those who will come after you.” [Ibid.]

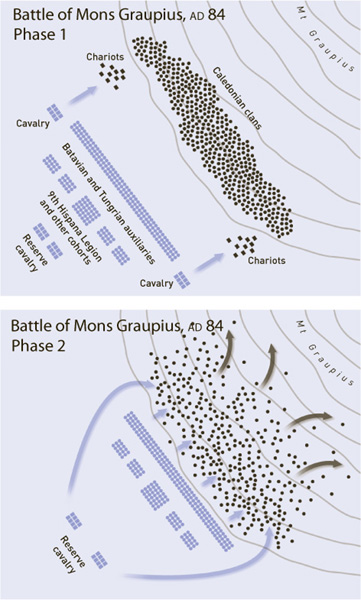

Answering the Caledonian call to arms were “all the young men and famous warriors,” the latter wearing decorations they had earned in previous battles, including, no doubt, trophies from skirmishes with the Romans. By the time that Agricola’s army had formed up, the Caledonian numbers had grown to such an extent that the Roman general “now saw that he was greatly outnumbered,” and, fearing that the tribesmen had sufficient numbers simultaneously to make a frontal attack on him and outflank both his wings, he ordered the ranks of his troops to open up so that his lines extended further across the plain. Agricola then dismounted, sent away his horse and took his place in front of the standards. [Ibid.]

With the tribesmen on the hill and the plain singing and yelling, and the Roman troops tense but perfectly silent, battle commenced. “The fighting began with an exchange of missiles,” said Tacitus. The Caledonian chariots charged forward, and passengers jumped down to launch their javelins. At the same time, the centurions of the auxiliary front line ordered their men to let fly with their spears. “The Britons showed both steadiness and skill in parrying our spears with their huge swords or catching them on their little shields.” [Tac.,

Agr

., 36]

One hundred and thirty years before, Caesar’s cavalry had destroyed the British cavalry sent against him. Now Agricola, keeping four squadrons in reserve, followed Caesar’s example, as he ordered most of his cavalry to charge the Caledonian chariots. His trumpet sounded, and the trumpets of the cavalry units repeated the call.

With a roar, the troopers on each Roman wing urged their horses forward, quickly reached the gallop, and charged into the Caledonian chariots, which appear to have begun withdrawing to the Caledonian wings.

As the cavalry engaged the chariots, Agricola gave another order. Trumpets again sounded. The standards of six auxiliary cohorts in the front line inclined forward. Yelling their battle cry, the 3,000 men of the two Tungrian cohorts and of four Batavian cohorts leapt forward and charged the Caledonian infantry, quickly surging into the opposition line on the plain. The auxiliaries’ commanders rode into battle; Aulus Atticus, young Roman prefect of one of these six cohorts, either driven by youthful impetuosity or carried on by an uncontrollable horse, pushed too far into the tribal ranks and found himself isolated. The Roman officer was quickly hauled from the saddle by Caledonians and slaughtered.

Roman auxiliaries behind the prefect maintained formation as they drove into the tribesmen. “The Batavians, raining blow after blow, striking them with the bosses of their shields and stabbing them in the face, felled the Britons posted on the plain and pushed on up the hillsides.” [Ibid.] Now the 5,000 remaining Roman auxiliaries were sent charging forward to join the fight. Meanwhile, the Roman cavalry had swiftly overwhelmed the Caledonian chariots, massacring their drivers and passengers. With the noblemen of all the tribes piloting these chariots, the Caledonians were deprived of many of their leaders. The Roman troopers now turned their attention to the infantry mêlée.

The Caledonian ranks on the slopes held firm against the impact of the Roman cavalry, and the rough ground made it hard going for horses. As a result, the Roman cavalry came to a standstill, and the troopers had to fight for their lives as the lanky tribesmen pressed forward around them. Roman auxiliaries, meanwhile, found themselves crushed up against the horses’ flanks. Occasionally, said Tacitus, a driverless chariot or a panic-stricken riderless horse would come crashing blindly into the mass of fighting men.

Higher up the hill, many Caledonians had yet to become engaged in the battle. An astute chieftain, perhaps Calgacus, seeing an opportunity to surround the outnumbered Roman auxiliaries, now sent these as yet unbloodied men rushing down the sides of the hill to outflank the Romans and attack them from the rear. Hundreds of yards away, Agricola, still standing outside the Roman camp with 9,000 stock-still legionaries aching to enter the fight behind him, saw the tribesmen come down off the

hill and sweep around to the rear of his auxiliaries. The general gave another order. In response, his four reserve cavalry squadrons galloped off and thundered across the plain, smashing into the Caledonians attacking the rear of the Roman auxiliary cohorts.

This cavalry charge turned the battle. The Caledonians, intent on attacking the auxiliaries, did not see the cavalry coming, and many were cut down from behind. Survivors from this group of Caledonians broke off the fight and ran for their lives, with Roman cavalry chasing them across the moorland. Overtaking tribesmen, Roman troopers would force them to disarm, taking them prisoner—they would bring a good price from the slave merchants who had followed the army north. But then, said Tacitus, troopers saw more Caledonians fleeing their way, and to prevent their first prisoners from escaping, they killed them, and then galloped off to make fresh captives of the latest terrified tribesmen on the run. [Tac.,

Agr

., 37]

The sight of the slaughter of their countrymen on the plain robbed the Caledonians still fighting on the hill of their spirit. The battle disintegrated into a rout. Large groups of warriors, while retaining their arms, deserted the hill fight and ran for the protection of distant forests. Auxiliaries gave chase. Agricola now ordered the legions forward, to mop up on the hill as he himself joined the pursuit by the auxiliaries.

As Caledonian dead littering the battlefield were being stripped by legionaries, Caledonian clans regrouped in the forests, and cut down the first rash Roman pursuers who ventured into the trees after them. Agricola ordered the auxiliary infantry to surround the forests, then sent the cavalry into the trees to finish the day’s work. “The pursuit went on until nightfall and our soldiers were tired of killing,” said Tacitus, who numbered the Caledonian dead at “some 10,000.” Agricola, he said, lost just 360 auxiliaries in the fighting. Not a single legionary had died, while the young prefect Atticus was the most senior of the Roman casualties. At nightfall, the Romans returned to their marching camp, exhausted but victorious.

“For the victors, it was a night of celebrating over their triumph and their booty,” said Tacitus. For Caledonian civilians, it was a night of searching the battlefield and the mounds of stripped bodies for their dead and wounded, and carrying them away. The Romans heard both men and women wailing in their grief that night. In the far distance, farmhouses glowed orange after being put to the torch by their owners, who fled with the survivors of the battle. [Tac.,

Agr

., 38]

Next day, with the naked Caledonian dead lying where they had fallen, “an awful

silence reigned everywhere.” [Ibid.] The hills were deserted. Smoke rose lazily from the ruins of distant farmsteads. Agricola sent cavalry scouts ranging for miles around. They found not a living soul. [Ibid.]

The most northerly battle ever fought by an imperial Roman army, and the last against war chariots, was a bloody victory for Agricola and for Rome, yet, apart from 10,000 bodies, glory and booty, it achieved little. With the summer almost at an end, Agricola and his troops withdrew to the south. No Roman army would ever progress this far north again.

The emperor Domitian recalled Agricola to Rome at once, and the Senate granted Agricola Triumphal Decorations. Agricola, fully aware that Domitian was jealous of his British success, immediately went into retirement and declined to be considered for any future official appointment.

AD

85–89

XXXVII. DECEBALUS THE INVADER

Prelude to Dacian conquest

Dacia, which encompassed much of modern-day Romania, was a mountainous country north of the River Danube populated by a Germanic people. Although theirs was primarily a rural economy, the Dacians had a high degree of commercialization and industrialization. Members of the Dacian ruling class were well educated, reading both Latin and Greek, and they also had substantial wealth, from Dacia’s rich gold, silver, iron and salt mines.

Up to this point in their history the Dacians had only seriously challenged Rome twice, and then only briefly, with raids into Moesia during the reign of Augustus and again in

AD

69, when the Roman Empire was in turmoil during the war of succession following the demise of Nero. On both occasions the Dacians had come off badly from their encounters with Rome’s legions. That situation was about to change.

In

AD

85, the elderly ruler of Dacia, King Dura, voluntarily abdicated in favor of a younger, more energetic man. Decebalus, the new king, was renowned for his military skills, both tactical and physical. The aggressive king Decebalus and his senior general Susagus, whose name meant “grandfather,” quickly assembled an army of foot soldiers from the tribes of mountainous Dacia, and led it across the Danube to

invade the Roman province of Moesia, taking the Roman garrison there completely by surprise.

“One after the other,” Tacitus was to complain, “experienced officers were defeated in fortified positions.” [Tac.,

Agr

., 41] The Roman governor of Moesia, Oppius Sabinus, hurriedly marched against the invaders with the 5th Macedonica Legion, then stationed at Oescus. [Suet.,

XII

, 6] In the ensuing battle the governor was killed by the Dacians, and the mauled 5th Macedonica fell back in disarray. The Palatium rushed the 4th Flavia Legion and auxiliary units to Moesia from Dalmatia, but the damage had been done. By the time the reinforcements arrived, Decebalus and his troops had sacked cities, towns and farms and taken thousands of prisoners, and, by the end of the year, had withdrawn across the Danube with their loot and their prisoners.

Domitian mounted an

AD

86 counter-offensive against the Dacians. He personally led an army into Moesia, but waited in the comfort of a Danube city as the prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Cornelius Fuscus, crossed the river with several legions, cohorts of the Praetorian Guard and numerous auxiliary units. In a mountain pass, Fuscus’ army was ambushed by Decebalus and his waiting Dacians. Fuscus was killed. One of his legions was wiped out, with its eagle and artillery carried away by the enemy. This legion was almost certainly the 5th Alaudae, which disappeared from the records at this time.

The 5th Alaudae was apparently commanded by Marcus Laberius Maximus, who perished with his unit. Laberius’ personal slave Callidromus, made a prisoner by Dacian general Susagus, was sent by King Decebalus as a gift to King Pacorus of Parthia. Thirty years later, Callidromus would escape back to his home town, Nicomedia, in Bithynia-Pontus.