LEGO (28 page)

Authors: Jonathan Bender

“What is this? A crocodile?” She laughs.

“Man’s last line of defense,” I say solemnly before I start laughing.

I’m not laughing thirty-six hours later when I open my suitcase at a friend’s house in Seattle. If I thought the TSA tore apart Joe Meno’s ray gun at Brick Bash, it’s nothing compared to the carnage that’s inside my luggage. Despite wrapping the bus in bubble tape and a few T-shirts, it’s been broken into three large parts, and one of the tires appears to be gone entirely. I freak out in silence, not wanting Sean to hear me get upset that my LEGO creation is ruined. That turns out to be a good decision. The bus is back together inside of fifteen minutes.

“This is sweet. We didn’t have parts like this when I was a kid. Is this a set?” asks Sean.

“No, I built it from scratch.”

Sean hasn’t seen a set in twenty years, but it feels good that he might think something I built came out of an official LEGO box. It makes me feel a lot less awkward when I’m standing in line to register for the seventh annual BrickCon. I still clutch the bus with an iron grip, accidentally snapping off a window because I’m certain I will drop it. I anonymously place it on the torn-up streets of the Zombie Apocafest display, next to a jeep filled with two murderous minifigs and a LEGO gun shop.

I notice a teenager in a black LEGO Universe jacket across the aisle. He’s fiddling with a NXT motor inside a LEGO baseball stadium, trying to sync the actions of a swinging batter, the crack of a bat, and then a crowd rising and falling to simulate cheering. The motor is buried under the pitcher’s mound, and John Langrish is getting frustrated that he can’t get the scoreboard to light up. I’m amazed that he’s built a scoreboard, let alone one that lights up.

I recognize the youngest of the forty LEGO ambassadors from pictures. John is very much the next generation of adult fans. He’s got a patchy black beard to match messy hair above glasses. I see a few interesting pieces that I know are in the LEGO Mars Mission box I found at a garage sale. I tell John about unearthing the box in the attic at an estate sale. I’ve discovered that every AFOL has a story of a big find. For John it was a standing rack of five drawers for $50, the top filled with rare elements including a whole turkey. The earth-orange turkey alone, which resembles a traditional Thanksgiving bird, goes for as much as $30 on BrickLink. It’s been out of production for close to a decade.

“I feel bad sometimes. I ask, ‘Are you sure your kids don’t want this?’ And they say, ‘Yeah, my kids are eighteen now.’” John pauses, beginning to laugh. “Well, I’m eighteen now, and I want it.”

“Is it ever hard to be the youngest in the room?” I ask him.

“These are people you meet once and you feel like you already know each other. There are forty-year-olds that I would otherwise never come into contact with, but we know each other because of LEGO,” says John.

Age is just a number when it comes to spring-autumn romances and playing with LEGO bricks. John gets the scoreboard to light up and tells me to lean in a little closer. Before he replaces the mound, I put my ear by the NXT brick. I hear the faint crack of a bat and the roar of a crowd, meant to accompany the baseball scene.

“We need to get a speaker,” says Aaron Dayman, a fellow member of the Victoria LEGO Users Group.

VICLUG has brought a bunch of Canadian builders to Seattle, the ease of a three-hour ferry ride lending the convention an international flair. Aaron has a baseball hat cocked slightly to the side and the raw enthusiasm of somebody new to the hobby.

“What do you like to build?” I ask Aaron, lobbing up the equivalent of an AFOL softball question, knowing how hesitant I was when attending my first convention.

“I build six-wide vehicles. Is that what you like to build?” says Aaron.

“I built a bus, but I didn’t think about it—this one just built itself,” I reply.

“So did I. Let’s go see them,” says Aaron.

He leans over the display, and I point him to the yellow bus.

“Can I?” he asks before picking it up. “The alligator is awesome—it scoops up the zombies, that’s the best.”

Aaron has built a sleek black bus filled with the kind of special operatives called in to deal with zombies in horror movies. Whereas my bus has exaggerated features and is built for comic effect, Aaron’s is streamlined to mimic a government vehicle. We built in the same category but with fantastically different results.

“Nice use of cheese wedges,” I tell him.

“I love those. I use as many as I can,” says Aaron.

This is what I envisioned when I sat building the school bus at my desk. It’s fun to chat with another adult fan about how they figured out an angle or why they chose a particular piece. We’re two guys talking shop.

I’ve been inside the Seattle Center Exhibition Hall for less than an hour when Tom Erickson waves in greeting.

“Hey, Jon the journalist. Want to come move a fourteen-foot LEGO boat?” asks Tom.

“Yes, I do.”

There is only one answer to a question like that. Tom walks me out to a red pickup truck. Dan Brown is driving, and my Yellow Castle wall building partner Thomas Mueller is in the backseat. Brett, a friend of Tom’s, rides shotgun. On the short drive to Sundance Yacht Sales, Dan tells me about the LEGO boat he has agreed to purchase for $5,500.

“I had to have this boat. You have to get anything made by Nathan,” says Dan. It’s as if Dan sniffs out models wherever he goes.

“Nathan” is Nathan Sawaya, one of only six LEGO certified professionals in the world. The certified professionals program basically allows talented builders to get access to discounts on bulk brick in exchange for agreeing to build within a set of standards established by LEGO.

Nathan was also one of the winners of the 2004 Master Model Builder Search at LEGOLAND. He became an instant media sensation; nobody leaves his job as a corporate lawyer to get paid $13 an hour to build with LEGO bricks. He left LEGOLAND less than a year later to explore a career as a LEGO artist, and the ten-foot boat we’re about to move is one of the models he built on commission in 2005. (Tom was off by four feet when he asked me to help, but it’s no less impressive.)

We pull up at Sundance Yacht Sales, where the blue-and-white LEGO boat sits on a blue table in the lobby of the office, which is down a narrow flight of stairs. It’s a LEGO-ized model of a nineteen-foot Chris-Craft Speedster. The boat has a propeller, rotating tan seats, and a steering wheel that turns. But the beauty of the boat is in the curved hull created from approximately 250,000 rectangular LEGO bricks. Nathan built it over the course of fourteen-hour days at the ten-day Seattle Boat Show; that’s how it ended up at Sundance.

“Good luck, boys, that thing is heavy,” says the owner. Nathan estimated it weighed close to a thousand pounds when he was finished.

Brett and Tom begin to unscrew a pair of sliding glass doors. The boat is too wide to carry up the narrow stairs, so that means we’ll be taking it out on this floor and wheeling it across the rickety wooden dock. The Sundance Yacht Sales office is, naturally, on the water.

Dan lays out a series of tools and asks me to grab an industrial roll of plastic wrap. He pries off pieces of the sculpture that he thinks could break off in transit. He slides out two windshield panes made from translucent bricks, the front seats of the speedboat, and a LEGO flag attached only by 1 × 1 cylinders.

After the boat is wrapped in plastic, the five of us together gently lift it and rest it on a four-wheel wooden dolly. I’m glad we’re only holding it for a few seconds. Not only is a ten-foot LEGO boat heavy, the bricks dig painfully into my fingers.

“Slow, slow,” says Dan as we wheel the dolly over the dock. The sides of the boat hang over the edges of the dock. He’s leaning out over the water at the first of three ninety-degree turns. Thomas and I are in front of the boat, while Brett and Tom push from behind. Water laps against the dock, which seems to be bowing a bit with the weight. A single LEGO brick will float, but if this boat goes in the water, Dan’s $5,500 investment will sink before we can go in after it.

Two concrete ramps connect the dock to the parking lot. The ramps are normally used for launching boats. The boat’s weight is staggering on the incline. I’ve worked up a good sweat in the thirty minutes it took us to go about six hundred feet. The rudder has snapped off, but the boat is mostly intact because it’s been glued. Thomas and Dan secure the boat to the truck with several layers of plastic wrap in order to keep it right side up, but a good two feet still hang out the back of the F150’s truck bed.

Seattle is not a flat city, and as we make our way through the hilly streets, I keep envisioning the boat rolling out the back, smashing on the concrete.

“Boy, I wonder what the police are thinking. It would not be easy to steal a LEGO model,” says Dan as we drive by two cops on traffic duty.

It’s not easy to do anything with a large-scale LEGO model. It’s so heavy and simultaneously fragile. And this isn’t like my bus; it can’t be rebuilt in just a few minutes. I have a greater appreciation for the effort it took for Dan to haul everything he has collected to Bellaire, Ohio, considering the challenges of moving a single piece just 1.6 miles.

The atmosphere is relaxed at BrickCon when we get back. LEGO community relations coordinator Steve Witt is launching Nerf gun projectiles from a raised balcony, attempting to hit LEGO skyscrapers. I see Breann Sledge, the Bionicle builder, camped out at the LEGO Group’s booth, piecing together an oversize Star Wars General Grevious set.

Each convention I’ve attended has had a different feel. Brick Bash was all about learning and playing with LEGO. Brickworld felt more serious, a place to develop building techniques from expert demonstrations. Brick Show was really an open invitation into Dan Brown’s collection. And BrickCon seems like a bunch of hobbyists who rented out a convention hall for the weekend. And for the first time, I’m one of those hobbyists. I’m not just observing, I’m one of the 235 people attending. This isn’t the first day of school, it’s coming back from summer vacation. It’s comfortable.

“I’ve been a LEGO addict for thirty years. I’m here to welcome you other addicts. I’m not here to get you away from LEGO, I’m here to get you more into it,” says BrickCon organizer Wayne Hussey during the opening ceremonies.

Wayne pauses when the crowd erupts in spontaneous applause. The opening speeches are interrupted as often as a State of the Union Address.

“This year we’re going to do the store differently,” says Wayne. “We want to make sure everyone has a chance to buy sets, and the numbered brick you have will determine when you get in the store. Also, guys, no reselling.”

Everyone is always anxious to go shopping at a nearby LEGO store, which is being kept open late with discounted sets as a bonus for adult fans.

“In the early days of LEGO conventions, like at the Potomac [Mills Mall] Store near BrickFair, LEGO stores had no idea how to handle adult fans. The scratch-and-dent were still in cardboard boxes. You would stand by the item you wanted most and when they blew the whistle, you could go for it. You would just rip and throw cardboard behind you. It was like hungry bears being taunted by a piece of meat on a stick. It’s hanging in front of them and then suddenly you give them a taste—it’s a feeding frenzy,” says Jim Foulds, the AFOL who is working on LEGO Universe.

LEGO has been working with convention organizers to figure out a method that will leave fans happy and spare the employees from having to clean up the carnage.

The speeches end soon and the convention attendees break up to figure out carpools and compare numbers. Until now, I never thought reselling was wrong. Tom Erickson has told me that the sets he sells at conventions often help him cover his travel costs.

“This is directed toward me,” says Dan on the way out to his truck, “but I’ll still get what I want.”

I’m sure he will, but it makes me wonder if I’m getting comfortable with the bad boys of the convention. Have I inadvertently sat in the back of the AFOL bus?

19

Building Blind and the Dirty Brickster

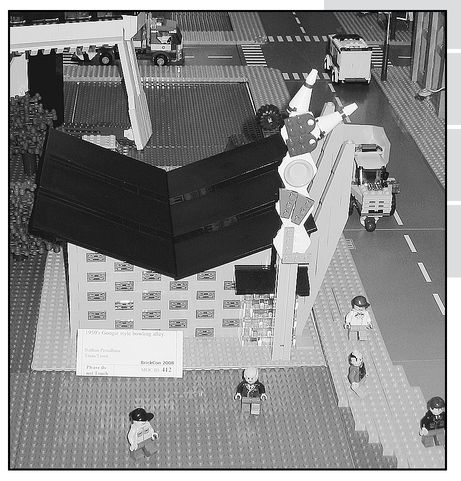

This retro LEGO bowling alley built by AFOL Nathan Proudlove was named one of the best buildings at BrickCon 2008.

I don’t feel the anxiety of the previous morning when I walk into the public display day at BrickCon on Saturday. This is where I belong. But with thirty-two hundred people waiting to see the LEGO creations inside, I start to get uneasy very quickly.

Who are you people? This

is the public, but I’m not part of them anymore. And when a man taking a picture of the thirty-foot LEGO

Titanic

elbows me out of the way, I want to get away from the crush of humanity as fast as possible. I look for the first door that says FOR CONVENTION ATTENDEES ONLY and rush inside. The door to Classroom A whisks closed, and I understand the fear of small spaces that sometimes overwhelms my mother.

Who are you people? This

is the public, but I’m not part of them anymore. And when a man taking a picture of the thirty-foot LEGO

Titanic

elbows me out of the way, I want to get away from the crush of humanity as fast as possible. I look for the first door that says FOR CONVENTION ATTENDEES ONLY and rush inside. The door to Classroom A whisks closed, and I understand the fear of small spaces that sometimes overwhelms my mother.

Other books

Seduced by the Wolf by Bonnie Vanak

The Doors Open by Michael Gilbert

Year of No Sugar by Eve O. Schaub

Billy Angel by Sam Hay

The Protector by Dee Henderson

Branded by Jenika Snow

Twisted Hills by Ralph Cotton

Ciudad by Clifford D. Simak

Alien Soulmate (Paranormal Romance Aliens) by Cristina Grenier

The Zero Hour by Joseph Finder