LEGO (27 page)

Authors: Jonathan Bender

“Building for many fans is a very personal thing or it’s tied into experiences with their family. If you are a true fan, you really have to sacrifice a bit of what you are comfortable with in order to explore a whole new side of the hobby,” says Jamie.

It’s not easy to learn how to build collaboratively. I have a hard time just working on sets with Kate; I can’t imagine how it would be if we were trying to free build together.

“My wife makes fun of me because I tell her when I see something that I can build it out of LEGO,” I say to Jamie.

I tell him about building my micro-monorails and the decision to use my favorite part, a 1 × 2 element that I have nicknamed the “lunch box.” Not surprisingly, he’s never heard the name, but he does think the part fits what I’m trying to do.

“People don’t need a lot of bricks to build something amazing. They just need to capture the essence of things—which it sounds like you did,” says Jamie.

It’s the first time I’ve talked about my part choices, and a set designer has just given me approval on the piece I picked. The near compliment leaves me feeling content with my progress as a builder.

Jamie is content as well, finally getting the access he’s wanted since running his fingers through three million bricks on the Millyard Project. He’s usually working on sets that use prototype elements at least two years in the future, with some platform projects that are at least five years out.

When Jamie was designing the Café Corner set, a modular building designed for advanced builders, he realized that LEGO didn’t make windows that would work for a modular building. The windows for the city theme were larger and boxy.

“Let’s make a system again and recapture what made LEGO special for so many fans. I was able to talk to the design lab about the value of having small windows that could be used over and over,” says Jamie.

AFOLs have raved about the Café Corner, Green Grocer, and Market Street sets. Despite the high price point, over $100 each, the sets have been well received because of their specialty elements. The recommended building age is sixteen-plus, and the detail on the modular buildings has inspired a new theme and standard for group displays.

“There is always tension because the desires and wishes of the fan community are often quite at odds with what the kids want. But I just try to get them to understand the company’s priorities and try to get them little gems once in a while,” says Jamie.

Those gems include the choice to build the Green Grocer in sand green, a prized rare color because it more closely mirrors actual building colors. But Jamie couldn’t include the LEGO equivalent of Easter Eggs found in DVDs—little surprises in the form of rare pieces or colors—if his coworkers didn’t understand the passion of adult fans. It’s not uncommon to see employees on a carpet, testing the durability of a car by pushing it around while making engine-revving noises.

“The fans are very protective of the brand, and it’s not just a company for them,” says Jamie. “But I genuinely feel that this is the one company where I’ve worked that has the consumer at heart.”

Other LEGO employees often approach Jamie to ask his opinion of how a set or product decision might be received.

“I’ve become kind of the in-house expert on adult fans. I’m not an expert, but at least I’ve got roots in the community, and if there’s a particular theme, I know who they should talk to,” says Jamie.

Besides Jamie, designers and the marketing department often turn to the Community Development team at LEGO—the group responsible for managing the company’s interaction with adult fans. Tormod Askildsen sits at the head of the group, and under him is Steve Witt in Enfield, Connecticut, and Jan Beyer, also based out of Billund. Jan (pronounced “yan”) is a Brooklyn hipster who just happened to be born in Germany. He is the main liaison for AFOLs in Europe and Asia, while Steve covers North America, Australia, and New Zealand.

“We’ve seen a real change over the past six or seven years. In the beginning there was just LUGNET, but now the whole landscape is filled with user groups online and has totally changed,” says Jan, his fingers adjusting his glasses.

I’m sitting across from Jan and Tormod back in the conference room by the offices of the New Business Group. They’ve been working to piece the adult community together the past five years, with Tormod being promoted to head the team in early 2008. They’ve managed to work adult fans into nearly every aspect of the sales process from production to presenting the final product.

“Designers find it inspirational to talk to fans, it’s like having a sparring partner,” says Jan.

The success of Mindstorms has provided a blueprint for how AFOLs can help launch and support products. Adult fans have also presented at trade shows and given holiday demonstrations in toy stores. Their knowledge and enthusiasm are effective marketing tools. It’s often Tormod or Jan who will introduce adult fans in an area to the local sales office, to establish a working relationship between the two groups.

“It can be frightening for LEGO employees because [adult fans] sometimes know more—both sides can be wary about the other,” says Jan.

I confess to Jan and Tormod that I don’t know very much about the adult community in Europe. I’ve taken a U.S.-centric look at the international toy, focusing on the world of the American AFOL based on my experiences growing up.

“European fans would say people in the United States build big, while American fans tell us that Europeans build small,” jokes Jan.

The Community Development group estimates there are approximately twenty thousand adult fans who belong to a hundred user groups, people they think of as “one e-mail away.” The LEGO Ambassador Program helps LEGO stay in front of those groups, with forty ambassadors representing hundreds of LUGs.

Many of the differences in how adult fans interact are, ironically, dictated by one of the defining aspects of LEGO’s instructions: groups in Europe and Asia aren’t as collaborative simply because of language barriers.

“They’re both building, but there’s a different style to events. The convention style is the dominant style in the United States, while in Europe, it’s more about exhibitions,” says Tormod.

At the close of the day, Jan Christiansen, my media representative, drives me back to LEGO headquarters on Systemvej, where I’m meeting Kate to begin the sightseeing portion of our trip to Denmark.

“One more thing,” says Jan when we arrive, pulling the Dwarves’ Mine set from his trunk. It’s a $100 set, as big as a briefcase. He moves to hand me the box.

“I can’t,” I tell him, putting my hands behind my back like a waiter asking if he can take your plate.

“C’mon. Nobody comes to LEGO and leaves without some LEGO,” says Jan.

“I don’t mean to be disrespectful, but I can’t accept the gift, because I’m a journalist,” I tell Jan.

“But you’re not a journalist; you’re a writer,” says Jan. I can’t argue with his logic.

“That’s true,” I reply, finally reaching out to take the box. We shake hands, and Jan heads home for the day. I take a seat on a concrete ledge somewhere near the buried molds and contemplate the first gift I’ve accepted as a journalist. I feel torn because of how badly I wanted to accept the set. Kate pulls up in our rental car.

She respects my ethics, but Kate always gets the wounded look of a child denied a promised trip when I tell her I refused an offer from an interviewee. She has chided me for turning down free beer, sports tickets, and vacations over the years.

“I took a gift,” I say, telling her the story.

“It’s so cool,” she says, turning the set over to look at the pieces, “Besides, Jan is right, you’re not a journalist, you’re an adult fan.”

On the car ride to Copenhagen, I’m glad that she knows what I am.

18

Good Luck, Boys, That Thing Is Heavy

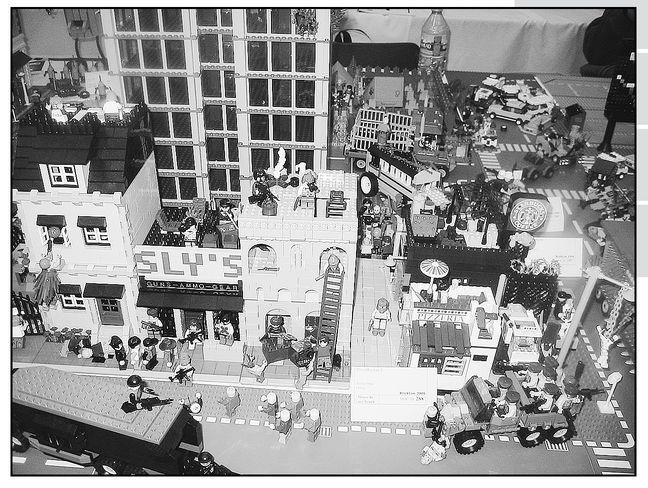

My LEGO bus sits smack in the middle of the Zombie Apocafest group display at BrickCon 2008 in Seattle, Washington.

The need to build grows like an itch. I’m starting to think that somebody with no impulse control couldn’t be an adult fan. I have a bucket of yellow and black bricks, the detritus that once was the Beach House set, in front of me. I told myself I wouldn’t take it apart; but when I needed a piece to complete the yellow whale, I didn’t hesitate to grab it off the house. Then, I said it would just be one piece. I could stop anytime I wanted. In two days, nearly the entire Beach House had been picked cleaner than a car left in Hollywood’s version of the bad part of town. I’m a parts junkie.

The Beach House is set to become a zombie defense vehicle, a rolling school bus that either runs over the undead or takes them prisoner. I’ve had zombies on the brain ever since Andrew Becraft announced on his Web site, the Brothers Brick, a collaborative display—the LEGO Zombie Apocafest—to be held at BrickCon 2008 in Seattle. Think

Shaun of the Dead

meets

Pleasantville.

I already told Andrew I’m bringing something. The only problem is that I haven’t built it yet, and the convention weekend is two days away—and we’ve just gotten back from Denmark.

Shaun of the Dead

meets

Pleasantville.

I already told Andrew I’m bringing something. The only problem is that I haven’t built it yet, and the convention weekend is two days away—and we’ve just gotten back from Denmark.

I take building inspiration from my conversation with Jamie Berard in Billund and am determined to be a participant in this adult fan convention.

“It’s a very nurturing culture, the community is good at encouraging your ideas especially when you are a fellow fan. So even if you didn’t have that as a kid, the community almost becomes like a surrogate parent cheering you on and patting you on the back,” said Jamie.

It’s like Little League: everybody plays, and some players are exceptional. Only, I didn’t play Little League. And I’m starting to doubt that I’ll ever be exceptional. But if Jamie’s right, that won’t matter, because ultimately it will be about participating.

I find a set of old oversize tires with white rims that dictate the size of the bus I’ll build. It’s going to be six studs wide. The largest vehicles I’ve built so far—the micro-scale trucks—are just two studs wide. A six-stud vehicle is minifig size and will need a minifig driver.

I had asked Jamie where he starts when he has to build a car for a set. “Start with something recognizable,” he told me. “Think of the front of the car as a face.”

I think of the windshield of the bus as eyes, and the grille as a mouth. I create the familiar arch of the front using sloped bricks, which resemble eyebrows, over the square translucent window elements. The hood is just a flat yellow plate, supported by a Technic brick. I draw out the sides, laying out alternating black and yellow plates to create the familiar striped pattern. Once I’ve got the basic shape of the bus, I begin to transform it into a zombie defense vehicle.

The details are what will make people stop and look at my MOC. It’s easy to attach a LEGO skeleton with a troll head to the Technic brick to create the illusion of a zombie speared by the grille. I also use several 1 × 1 plates with clips so that I can attach weapons to the side of the bus. I find a chainsaw and an oversize wrench that I clip along the side. An inverted 2 × 2 red plate gives the idea of a stop sign by the driver’s window. I steal chains from a medieval LEGO coinbank that Kate bought me to crisscross around the open roof. At this rate, my office is beginning to have sets that look like they came from the Island of Misfit Toys.

The banisters from the Beach House make the perfect bars of a zombie prison. To finish the bus, I add touches that make me laugh. A street sweeper minifig sits inside a trash can on the roof of the bus, guns at the ready. The final piece I build is a small shelf on the undercarriage, just big enough to hold a LEGO alligator.

This MOC means something more to me because it consists of bricks from my entire collection. There are tires from my brother-in-law Ben’s bricks, yellow pieces from sets I’ve bought, windshields from a Pick A Brick cup, and skeletons from Brickworld. The zombies are troll heads repurposed from the Castle set I picked up in Denmark. It is a physical representation of how much my part knowledge has increased.

When I’m finished, I roll the bus along my desk and find myself inventing a back story for the minifigs. It’s an unlikely friendship struck up by two city employees, the last vestiges of a government literally torn apart by zombies. But if Frank the street sweeper and Tomas the airport manager (which Kate thinks is the job for every LEGO city minifig) have anything to say about it, the city will survive the Apocafest.

“A lot of adults might say they don’t play,” said Jamie during our conversation, “but perhaps they do play. It’s a little bit of a dirty secret, that almost all adults like the idea of being able to play even if they don’t have the time or don’t actually play with what they’ve built.”

Kate walks into my office and finds me playing.

“I’m just making sure it rolls right,” I tell her, instead of admitting that I was envisioning Frank and Tomas battling hordes of zombies.

“Whoa, cool bus,” says Kate. It’s the first time she has recognized what I’ve built immediately. It is awesome. She picks it up, and her fingers brush against the alligator.

Other books

State of Rebellion (Collapse Series) by Lane, Summer

Number of the Beast (Paladin Cycle, Book One) by Lita Stone

The Bear Went Over the Mountain by William Kotzwinkle

The Keeper: Alexa LeGardien by Reade, Kaytie

Whitefire by Fern Michaels

Mad World by Paula Byrne

The Last Gentleman by Walker Percy

Passion's Song (A Georgian Historical Romance) by Carolyn Jewel

Goldengrove by Francine Prose

Broken Things by G. S. Wright