Letters to Jackie (2 page)

Authors: Ellen Fitzpatrick

Jaqueline Lee and John Fitzgerald Watson, twins named after the Kennedys

Photograph of John Fitzgerald Watson and Jacqueline Lee Watson, reprinted with permission of Mrs. William B. Watson Jr.

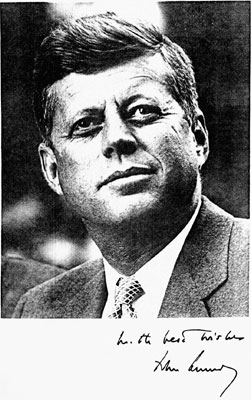

A news report that Caroline Kennedy had broken her wrist prompted a letter to the President’s daughter with a picture of the writer’s pet dachshund, sporting a cast on his leg. Some sent to Mrs. Kennedy photographs of the President, which they had taken at campaign rallies and other public appearances. Texan John Titmas enclosed in his condolence letter the two poignant photographs of President and Mrs. Kennedy on this book’s jacket, which he took at Love Field less than an hour before the assassination.

As letters continued to pour in, Jacqueline Kennedy made a brief television appearance seven weeks after the President’s death, in which she thanked the American people for their expressions of sympathy. Mrs. Kennedy’s remarks on January 14, 1964, gave the public their first glimpse of the

President’s widow since the state funeral on November 25. Flanked by her brothers-in-law Attorney General Robert Kennedy and Senator Edward Kennedy, and wearing a simple black wool suit, Jacqueline Kennedy spoke for only two minutes and fifteen seconds. She thanked the nation for the “hundreds of thousands of messages…which my children and I have received over the past few weeks.” “The knowledge of the affection in which my husband was held by all of you has sustained me,” she continued, “and the warmth of these tributes is something I shall never forget. Whenever I can bear to, I read them. All his bright light gone from the world.” Noting that “each and every message is to be treasured not only for my children but so that future generations will know how much our country and people of other nations thought of him,” she promised the public that “your letters will be placed with his papers” in the Kennedy Library, then already in the

planning stages. Her touching remarks, as well as her assurance that each message would be acknowledged, prompted a new avalanche of condolence letters, with many writers apologizing for their tardiness.

Condolence card, John F. Kennedy Library.

In the ensuing months, Nancy Tuckerman and Pam Turnure, Mrs. Kennedy’s secretaries, oversaw the monumental project of handling the condolence mail. They supervised a cadre of volunteers who responded not only to each letter but also to requests from the writers for Mass cards or photographs of the President, Mrs. Kennedy, or the former First Family. Most correspondents received in reply a black bordered note card with President Kennedy’s coat of arms centered on it, with the simple message: “Mrs. Kennedy is deeply appreciative of your sympathy and grateful for your thoughtfulness.”

Photograph of John F. Kennedy, John F. Kennedy Library.

Sorting the mail itself proved to be a task of gargantuan proportions. A consultant hired to advise about a system for handling the letters admitted

he was flummoxed. Early in the process famed anthropologist Margaret Mead sent word to Nancy Tuckerman, through a cousin of Tuckerman’s, that an effort should be made to sort letters into categories, given the value the collection would have for future generations of scholars. Despite the additional workload this entailed, Tuckerman complied. Volunteers separated adult letters from children’s, labeled certain items “especially touching,” and created various other subsets such as special “requests.” Two men from Attorney General Robert Kennedy’s staff helped Tuckerman and Turnure create a method of sorting the letters. As late as May 1966, Mrs. Kennedy’s staff was still sifting through and cataloging the condolence letters. “Mrs. Kennedy is reluctant to throw things away,” Pam Turnure reported to the

New York Times

. “She feels it all came from the heart and who is to know in the future how much any letter or poem or painting will show about how people felt.” Of the task involved in handling the condolence mail, Turnure said: “We are doing all we can so that it will be available for work by scholars.” And yet, for forty-six years, the letters have sat in the Kennedy Library with little sustained scholarly attention.

When the condolence mail was officially deeded over to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston in 1965, it comprised some 1,570 linear feet (that is, the boxes would have extended more than a quarter of a mile if laid end to end). The size of the collection and issues in storage and management posed formidable problems. Eventually these difficulties led the National Archives to pulp all but a representative sample of the condolence mail. The remaining documents represent some 170 linear feet—over 200,000 pages. The team of archivists who sorted through the 830 cartons of general condolence mail saved letters from each major category and created new subsets as they saw fit. All letters offering personal recollections of JFK were retained, as were messages from VIPs, noteworthy mostly for the famous name attached. The enormous volume of foreign mail, some in English but much in the letter writers’ own language, was preserved in large measure, organized by country. “Touching,” “good,” and “representative” letters were also kept—many of them labeled as such by the volunteers who had helped answer the letters. Luckily, the archivists

also set aside a random sample of 3 linear feet (approximately 3,000 letters) of the general condolence mail from Americans “as an example of the original inflow of messages to Mrs. Kennedy.”

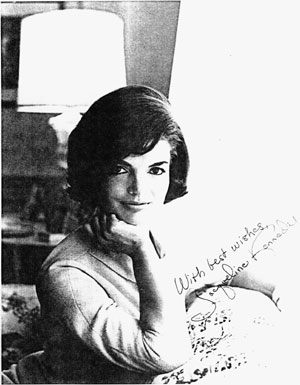

Photograph of Jacqueline Kennedy, John F. Kennedy Library.

Mrs. Kennedy received very few negative letters. The archivists processing the collection noted an almost “total absence of any letter or comment critical of the president,” although several letter writers objected to the President’s advocacy of civil rights for African Americans and a very few others viewed him as weak in his attempts to combat the spread of Communism. Presumably those who despised the President found venues other than a condolence letter to express their sentiments. It is in the nature of the genre, of course, that praise, warm memories, and generosity toward the deceased predominate in sympathy messages. The assassination itself, to be sure, contributed to a growing hagiography of JFK that began to take shape from the moment of his death. Still, it is well to remember that during his lifetime Kennedy remained among the most consistently popular of Presidents. Only during the final three months of his life, when a growing number of Americans objected especially to his initiation of civil rights legislation, did his approval rating ever slip below 60 percent—and then only to 56 percent. His average approval rating during his Presidency exceeded 70 percent—higher than that of any other modern President.

The political culture then extant in America surely contributed to Kennedy’s idealization. In the early 1960s, the office of the Presidency and the man who held it enjoyed from most Americans a kind of deference that would soon appear a relic of a bygone era. Such fundamental respect and, for some, adulation could flourish, in part, because of a relationship between the President and the press far different from that in contemporary America. An unwritten code of conduct among journalists largely protected John F. Kennedy, as it had previous Presidents, from close scrutiny and publicity about his personal life and, therefore, from scandal. Among the press corps rumors and salacious gossip about Kennedy’s private life abounded, but very little of it ever found its way into mainstream news outlets. Kennedy, of course, had his outspoken critics, and the press aggressively covered the ups and downs of the President, his policies, and his administration. JFK

never confronted, however, a press likely to expose details of his private life, medical history, or personal relationships that might have undermined the image he projected. Nor did Kennedy face the twenty-four-hour cable news cycle, with its relentless blend of inquiry, opinion, and commentary, much of it giving free voice to highly partisan critics, which would become a reality for later Presidents.

The deep skepticism, with which both press and public often now view government itself, and political office holders of every level, also was far less apparent in Kennedy’s era. The infamous “credibility gap” that widened through the long, torturous, and costly engagement in Vietnam, bequeathed to and then inexorably widened by President Lyndon Johnson, badly eroded confidence in the Presidency. Determined and repeated efforts to put the best face on the progress of the American engagement in Southeast Asia, despite mounting casualties and growing public concern that the war was unwinnable, in time damaged the faith many placed in the nation’s Chief Executive. That basic trust, buffeted though it often was, reached its nadir in the Watergate scandal during Richard Nixon’s term of office. Brilliant and dogged investigative journalism eventually brought down the Nixon White House and with it, at least for a time, public confidence in the Presidency.

The public’s sense of personal engagement with President Kennedy was also enhanced by extensive press coverage of the youthful, vivacious First Family. Kennedy’s political fortunes soared during the campaign of 1960 in part through his mastery of television. Throughout his time in office, JFK used his facility with this relatively new medium to great advantage. Many letter writers mentioned the utter delight they took in his weekly news conferences—the first to be carried live on radio and television. Kennedy’s self-deprecating humor, dry wit, and ability to spar adroitly and easily with the press captivated many viewers. One such citizen recollected, “my husband & I use to get such a kick out of President Kenedy when the News Reporters used to surround him with questions all he had to do is just open his mouth the Answers just flowed out. He never had to study for a minute.”

Kennedy’s frequent televised appearances clearly entertained some viewers. But he also used the press conferences to explain directly to the

American people his policies and intentions, bypassing the interpretive layer imposed by administration officials and political commentators. “Mr. Kennedy taught my children many things on television,” an African American mother from Oakland explained, “because they were interested in him and always wanted to listen to his speeches and my youngest son, Rudolph loved his press conferences and tried to imitate him in many ways.” It’s been estimated that by the second year of Kennedy’s presidency, three out of four adults had seen or heard a Presidential news conference. In 1962, over 90 percent approved of Kennedy’s performance. Jacqueline Kennedy, whose sense of fashion, glamour, and interest in the arts enlivened the Kennedy White House, also attracted much public attention. Her February 1962 televised tour of the White House, showcasing her efforts to restore and preserve the historic mansion, drew three out of four television viewers.

With a newborn and a three-year-old, the Kennedys brought the youngest children to the White House of any Presidential family in the twentieth century. The press covered both Caroline and John F. Kennedy Jr.’s activities as extensively as their parents would permit. Many young parents of the World War II generation, who were busy in the early 1960s raising their own children—the baby boomers—strongly identified with the young White House couple.

New media, the culture of celebrity that they enhanced, and the Kennedys’ considerable personal appeal converged in the early 1960s to make them the most familiar and closely watched of First Families, all of which enhanced the President’s appeal to the American public. Still, JFK’s personal qualities surely created some of the magic. Those letter writers who describe even momentary encounters with President Kennedy—a handshake, a wave, a brief conversation—remembered a warm and engaging man whose enjoyment of politics was palpable, who seemed sincere in his convictions, and who appeared to take delight in meeting them. These realities, of course, deepened the personal anguish many Americans felt after Kennedy’s assassination. There was much, of course, the public did not know until many years after, but those revelations lay in the distant future.