Letters to Jackie (4 page)

Authors: Ellen Fitzpatrick

Spectators reacted immediately to the sound of gunfire, many running

away from the street or throwing themselves to the ground. Several of those closest to the Presidential car turned toward the Book Depository when they heard gunfire. Among them was Bob Jackson, a photographer for the

Dallas Times Herald

, who was seated in an open car reserved for cameramen toward the rear of the motorcade. He looked up in time to see a rifle being pulled back from a sixth-floor window in the Depository. Tom Dillard of the

Dallas Morning News

, also in this convertible, quickly snapped a photograph of the sniper’s perch.

Before the Presidential limousine even reached Parkland Hospital, a distance of less than four miles that nonetheless felt like an “eternity” to Jacqueline Kennedy, news of the assassination attempt began to break. Merriman Smith, the White House Correspondent for UPI, was riding in the press pool car just in front of the photographers when he heard the gunfire. He grabbed the radiophone and called his Dallas bureau, shouting: “Three shots were fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade in downtown Dallas.” The bulletin came off the UPI teletype at 12:34, setting in motion a cascade of breaking news stories. At 12:36—just as the President’s car reached Parkland Hospital—ABC radio interrupted its programming to read the UPI flash. At 12:40 CBS broke into its popular soap opera

As the World Turns

with a special bulletin read by Walter Cronkite: “In Dallas, Texas, three shots were fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade in downtown Dallas. The first reports say that President Kennedy has been seriously wounded by this shooting.” Updates by wire report, radio, and television rapidly tumbled in. By 1:00 p.m., when doctors at Parkland pronounced the President dead, it’s been estimated that nearly 70 percent of adults in the United States already knew of the assassination attempt. At 1:35 another UPI bulletin came across the wire: “President Kennedy dead.”

As these events unfolded, word of them reached Americans who were going about their day only to be stopped short. Their subsequent letters of sympathy to Mrs. Kennedy reveal how the drama of November 22 collided with the lives of individual Americans, both on the scene in Dallas and far removed from Texas. Some began their letters as they sat watching news of

the assassination break on television. There are no letters from eyewitnesses in the condolence letters, but there are many from bystanders who saw the President and Mrs. Kennedy only minutes before the assassination. Others wrote weeks, months, and even a year later, but described with extraordinary clarity precisely what happened in their own lives on November 22. The first letters below are arranged chronologically, based not upon the date of their letter, but of the day’s events. They are followed by messages that depict the way the news reverberated around the country.

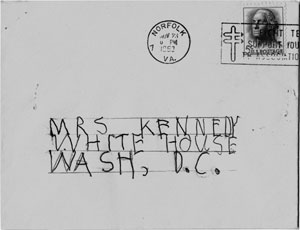

Photograph of envelope, Condolence Mail, John F. Kennedy Library.

VALLEY CENTER, CALIF.

NOVEMBER 22, 1963

Dear Mrs. Kennedy,

Nothing has been confirmed as yet. Either way it turns out you have my deepest sympathy.

Don’t neglect the healing affect of quiet time alone with a quiet horse or dog.

Oh my dear, it has been pretty well confirmed that we have lost him. Our prayers are with you.

Love,

Nancy, Kenneth,

Rick, Brandon

& Perry Glimpse

UPPER DARBY, PA.

11/22/63

2:00

P.M.

My dear Mrs. Kennedy.

Even as I write this letter, my hand, my body is trembling at the terrible incident of this afternoon. I am watching the CBS-TV news report. No official word as yet. I’m not of voting age yet but I am old enough to understand the political and diplomatic relations of the world. When the President was campaigning, If I had been old enough, I would have voted in his favor. I knew that then and I know that now. Not because of his youth, his religion, his personality. But because of some indistinguishable influence, perhaps more defined now after a few years, almost a full term, after his election.

I’m writing, I know, but what I want to say, I can’t put into words. Perhaps you can read between the lines. Not just “I’m sorry to hear….” but more.

Good God! Help us! Help us! Three assassinations are now history and I never thought I’d live to see one, even a thwarted attempt which was close but not, Saints help us SUCCESSFUL. It is a terrible thing to live through.

I can’t go on writing now. It’s too much. My prayers are with you and those involved.

Larry Toomey

11/22/63 2:45 P.M.

DALLAS TEXAS

DEC.

1-1963

Mrs Jacqueline Kennedy

First Lady in our hearts.

I live in Dallas, a city bowed in sorrow, and shame. I am 76 years old and live on a social security check

I must pour out my heart to you if my feeble hands will hold out to scribble a few lines.

I was at Lovefield, when you and John steped from the plane. I was the first man to shake his hand, (from behind the fence barricade). That was my life’s fullest moment.

And you! The camera’s were on you, most of that dark day. Heaven must have fortufied you for those hours. No Pen or brush nor gifted tongue could have accurately portrayed your stature in lonliness. Humility, bravery, fortitude, beauty, strength, faithfulness, loyalty, loveliness, and grandure, Rolled into one Sweet Mrs. Amerec of the Ages.

Very Sincerely,

J.E.Y. Russell

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS

MAY

28, 1964

Dear Mrs. Kennedy,

The following letter is a copy of a letter that I wrote to a parish priest (Episcopal) who moved away from this area some time ago.

I thought perhaps you would know by this letter that there are those who will never forget your husband and who will always miss him. Even now, six months afterward, unexpected tears spring to my eyes every time I see a film of him on television. Even now it is so hard to believe. I whisper to myself, “Surely this can’t be so!”

Your beautiful picture on the cover of

Life

and your article prompted me to write to you. I hope I have given you some comfort.

Most sincerely,

Janice Crabtree

(Mrs. W.C.)

November 27, 1963

Dear Father,

May I share a few thoughts with you about the tragedy? Nothing has touched me so deeply in a long time. I had seen President Kennedy just three or four minutes before he was shot. I had planned all week to go to the parade in downtown Dallas, but the morning dawned foggy, misty and ugly. Billy insisted that I stay home and watch the motorcade on television. But by 9:30 a.m. I couldn’t sit still any longer. I put on my oldest raincoat and overshoes and dashed to Dallas. I parked way down on Pacific, and was the last car that that lot could take. Excitement was in the air, and I was glad to be alone so I could soak it up without the necessity of polite conversation with anyone. I walked slowly, trying to kill the long wait…. Finally I decided to go to Neiman’s Zodiac Room for a snack, but they were having a private

brunch until noon, so I sadly turned away. As I did so, I saw the Beauty Salon, and right there decided to get my hair cut. I was happily surprised that they could take me. I told them that I couldn’t wait, because I wanted to see the President.

When I came out of Neiman’s with my new haircut at 11:10, crowds were already forming. It was quite heartening, because I had worried so about his reception in Dallas. I hurried down to Daddy’s old office building, the former Republic Bank Building, now the Davis Building. Jacqueline Kennedy is not the only one with outstanding sentiment—I wanted to see the President right in front of the doorway that my father used thousands of times, and I wanted to try to imagine and feel the elation that he would have felt about seeing his favorite of all presidents. To Daddy, President Kennedy was too good to be true—he worried constantly about an untimely death for him. I remember his astounding statement at the time of the 1960 Democratic Convention, when Johnson accepted the vice-presidency and so many of Johnson’s fans were sick—Daddy said, “Kennedy will be elected, then assassinated, and Johnson will be president, after all.” I thought of this during the long wait. I looked up at the windows of the tall buildings and thought about the utter futility of trying to protect him. The thought crossed my mind that a bomb tossed from one of those windows could kill a bunch of us, too, but even that did not induce me to move from my perfect spot. The crowd grew and grew. Soon rooftops and awnings were crowded. Right across the street an enormous sign was put up. It said, “We’ll trade U one retired general for some NASA artwork. Signed 250 Dallas artists.” Police cars made constant patrols, looking, watching. A police truck hauled off a car that was left on Main Street.

I wondered what the owner of the car would think when he returned and couldn’t find his car. The crowd was very jovial and those of us who shared the long foot-tiring wait became like neighbors.

A couple of incidents brought real laughter from both sides of the street. One was a powder blue car with bright writings all over it. It would go past us, catching all eyes, then pretty soon it would come back. We began to clap on about the third pass, and on the last we cheered—the writing on the car said, “Shop at Honest John’s Pawn Shop,” and the shrewd owner was taking advantage of the great crowd. The other incident had to do with two high school boys in a convertible—one was driving and the other sat in the back seat smiling and waving with an expression on his face like a great leader. The amiable crowd rewarded the boy with light applause and good humor. I heard only one ugly remark about President Kennedy—a squat sour-looking old man came out of Daddy’s doorway, pushed his way to the curb, looked at the size of the crowd, and said, “All you people here to see that guy?” Of course, no one answered him and he hurried back inside. A young girl next to me had a transistor radio, and we were able to hear on-the-spot reporting about his wonderful welcome at Love Field, about his friendly handshaking, Jackie’s beauty and everything—the excitement was mounting. Finally, the police turned away all traffic, and Main Street was empty at noon. The police cautioned us to stay on the curb, but we couldn’t resist dashing out into the quiet street for a long look to see if the motorcade was approaching. At last it came into view, and that first sight of it filled me with such incredible excitement that I don’t believe I can describe it—indeed,

even to write of it starts my heart pounding. The first thing I was able to see at several blocks distance were the red lights of the motorcycle police escort—about eight flashing red lights preceding the dark limosine. They were travelling faster than I had expected. The police were yelling to stay back, but from both sides of the street we surged out. I almost got my toe run over by one of the motorcycles. Long as I live I will never forget Kennedy—tanned (that was the first thing that I noticed) smiling, handsome, happy. I didn’t get to see Jackie’s face, because she was waving to her side of the street, but her youthful image was unmistakably beautiful. Her long mahogany-colored hair was blowing in the wind, and the sun, which had come out brilliantly, caught the red highlights. I’ll always remember the way it shone so brightly on the President. Then they were gone.

I was shaking so, as I made my way back to the parking lot, that I decided I’d better stop on the way home and eat a bite of lunch. I got into my little Opel and turned on the radio. The first thing I heard was, “The President has been shot,” and I just thought that the announcer had meant to say that the President has been shocked at the size and friendliness of the crowd. All too soon the terrible truth sank in and I don’t know how I got home. I couldn’t go into my house alone, so I went to the neighbors. They were white-faced and weeping. Their television was on and the announcer had just said that our good, wonderful, youthful President was dead. One of my neighbors had attended the breakfast in Fort Worth that morning—

Needless to say, I never did eat lunch or supper. I never made up a bed, got together a meal, nor paid a bill until after the funeral. I even almost forgot that my beloved Mother had died on November 24th, and was buried on Billy’s birthday,

November 26th. Today is my own birthday and it means nothing. I am sick, sick, and violently angry.

Pray for us all, please.

Janice

P.S. Would you mind sending this back to me? I would like to keep this written account for my sons, Billy and Jim.

Dear Mrs. Kennedy:

I know the grief you bear. I bear that same grief. I am a Dallasite. I saw you yesterday. I hope to see you again. I saw Mr. Kennedy yesterday. I’ll never see him again. I’m very disturbed because I saw him a mere 2 minutes before that fatal shot was fired. I couldn’t believe it when I heard it over the radio 5 minutes later. I felt like I was in a daze. To Dallas, time has halted. Everyone is shocked and disturbed. My prayers to you.

A Sympathetic, Prayerful, and Disturbed

DALLASITE,

Tommy Smith

Age: 14

S

ome bystanders waiting to catch a glimpse of President Kennedy instead saw the motorcade as it sped toward Parkland Hospital. One woman who later wrote to Mrs. Kennedy received a call from her brother who witnessed the arrival of the presidential limousine at the hospital. “Calls for stretchers rang out—and you know too clearly the rest,” she noted. “John, my brother, helped take your John, by stretcher to the Emergency Room…. I saw my brother around 2:00 p.m. that afternoon. He was visibly shaken.” A nursing home administrator who

happened to be at Parkland that day with a patient recalled, “I saw your beloved husband when they brought him in on the stretcher to the emergency room…. I am sorry I was unfortunate to have to see your wonderful husband on his day of death.” Others waited for the motorcade to arrive at the Trade Mart.