Leviathan (8 page)

Authors: Scott Westerfeld

TWELVE

As Deryn and Newkirk neared the bow, the bats grew louder, their echolocation chirps rattling like hail on a tin roof.

The other middies were just behind, Mr. Rigby in their midst, urging them to hurry. The bats’ feeding had to be timed precisely with the fléchette strike.

Suddenly a shrieking mass of havoc swept out of the darkness—an aerie of strafing hawks, aeroplane nets glimmering in the dark. Newkirk let out a startled cry, his feet tangling together. He tumbled down the slope of the air-beast’s flank, his rubber soles squeaking along the membrane. Finally he came to a halt.

Deryn dropped her bag and scuttled after him.

“Barking spiders!” Newkirk cried, his necktie more askew than usual. “Those godless birds attacked us!”

“They did no such thing,” Deryn said, offering him a hand up.

“Trouble keeping your feet, gentlemen?” Mr. Rigby called down from the spine. “Perhaps some light on the subject.”

He pulled out his command whistle and piped out a few notes, high and raw. As the sound trembled through the membrane, glowworms woke up underfoot. They snaked along just beneath the airbeast’s skin, giving off enough pale green light for the crew to see their footing, but not so much that enemy aircraft could spot the

Leviathan

in the sky.

Still, combat drills were supposed to be conducted in darkness. It was a bit embarrassing to need the worms just to

walk

.

Newkirk looked down, shuddering a little. “Don’t like those beasties either.”

“You don’t like

any

beasties,” Deryn said.

“Aye, but the crawly ones are the worst.”

Deryn and Newkirk climbed back up, now behind the other middies. But the bow was within sight, the bats covering it like iron filings on a magnet. The chirping came from all directions.

“They sound hungry, gentlemen,” Mr. Rigby warned. “Be sure they don’t take a bite of you!”

Newkirk made a nervous face, and Deryn elbowed him. “Don’t be daft. Fléchette bats only eat insects and fruit.”

“Aye, and metal

spikes

,” he muttered. “That’s barking unnatural.”

“Only what they’re designed to do, Newkirk,” Mr. Rigby called. Though human life chains were off-limits for fabrication, the middies often conjectured that the bosun’s ears were fabricated. He could hear a discontented murmur in a Force 10 gale.

The bats grew noisier at the sight of the feed bags, jostling for position on the sloping half sphere of the bow. The middies clipped their safety lines together and spread out across the swell of the ship, feed bags at the ready.

“Let’s get started, gentlemen,” Mr. Rigby shouted. “Throw hard and spread it out!”

Deryn opened her bag and plunged a hand in. Her fingers closed on dried figs, each with a small metal fléchette driven through the center. As she threw, a wave of bats lifted, wings fluttering as fights broke out over the food.

“Don’t like these birds,” Newkirk muttered.

“They ain’t birds, you ninny,” Deryn said.

“What else would they be?”

Deryn groaned. “Bats are mammals. Like horses, or you and me.”

“Flying mammals!” Newkirk shook his head. “What’ll those boffins think of next?”

Deryn rolled her eyes and tossed another handful of food. Newkirk had a habit of sleeping through natural philosophy lectures.

Still, she had to admit it was barking strange, seeing the bats eat those cruel metal fléchettes. But it never seemed to hurt them.

“Make sure they all get some!” Mr. Rigby shouted.

“Aye, it’s just like feeding ducks when I was wee,” Deryn muttered. “Could never get any bread to the little ones.”

She threw harder, but no matter where the figs fell, the bullies always had their way. Survival of the meanest was one thing the boffins couldn’t breed out of their creations.

“That’s enough!” Mr. Rigby finally shouted. “Over-stuffed bats are no good to us!” He turned to face the midshipmen. “And now I’ve got a little surprise for you sods. Anyone object to staying dorsal?”

The middies let out a cheer. Usually they climbed back down to the gondolas for combat drills. But nothing beat seeing a fléchette strike from topside.

The H.M.S.

Gorgon

was within range now, pulling a target ship behind. The target was an aging schooner that carried no lights, but her sails were a white flutter against the dark sea. The

Gorgon

cut her loose and steamed to safety a mile away. Then sent up a signal flare to show that she was ready to start.

“Out of my way, lads,” came a voice from behind them. It was Dr. Busk, the

Leviathan

’s surgeon and head boffin. In his hand was a compressed air pistol, the only sidearm allowed on a hydrogen breather. He waded in among the bats, their black forms skittering away from his boots.

“Come on!” Deryn grabbed Newkirk’s arm and scuttled down the slope of the airbeast’s flank for a better view.

“Try not to fall off, gentlemen,” Mr. Rigby called.

Deryn ignored him, heading all the way down into the ratlines. It was the bosun’s job to take care of middies, but Rigby seemed to think he was their mum.

A message lizard scrambled past Deryn and presented itself to the head boffin.

“You may begin your attack, Dr. Busk,” it said in the captain’s voice.

Busk nodded—like people always did to message lizards, though it was pointless—and raised his gun.

Deryn hooked an elbow through the ratlines. “Cover your ears, Mr. Newkirk.”

“Aye, aye, sir!”

The pistol exploded with a

crack

—the membrane shuddering beside Deryn—and the startled bats rose into the air like a vast black sheet rippling in the wind. They swirled madly, a storm of wings and bright eyes. Newkirk cowered beside her, pulling himself closer to the flank.

“Don’t be a ninny,” she said. “They’re not ready to loose those spikes yet.”

“Well, I’d hope not!”

A moment later a searchlight beneath the main gondola flicked on, its beam lancing out across the darkness. The bats headed straight into the light, the blended life threads of moth and mosquito guiding them as true as a compass.

The searchlight filled with their small fluttering forms, like a shaft of sun swirling with dust. Then the beam began to swing from side to side, the horde of bats faithfully tracking it across the sky. They spilled out along its length, closer and closer to the target fluttering on the waves.

The swing of the searchlight was perfectly timed, bringing the great swarm of bats directly over the schooner …

… and suddenly the light turned blood red.

Deryn heard the shrieks of the bats, the sound reaching her ears above the engines and war cries of the

Leviathan

’s crew. Fléchette bats were mortally afraid of the color red— it scared the deadly clart right out of them.

As the spikes fell, the horde began to scatter, exploding into a dozen smaller clouds, the bats swarming back toward their nests aboard the

Leviathan

. At the same time the searchlight dipped toward the target.

The fléchettes were still falling. In their thousands, they shimmered like a metal rain in the crimson spotlight, cutting the schooner’s sails to ribbons. Even at this distance Deryn could see the wood of the deck splintering, the masts leaning as their stays and shrouds were sliced through.

“Hah!” Newkirk shouted. “A few like that should teach the Germans a lesson!”

Deryn frowned, imagining for a moment that there were crewmen on that ship. Not a pretty picture. Even an ironclad would lose its deck guns and signal flags, and an army in the field would be savaged by the falling spikes.

“Is

that

why you signed up?” she asked. “Because you hate Germans more than fabricated beasties?”

“No,” he said. “The Service was my mum’s idea.”

“But isn’t she a Monkey Luddite?”

“Aye, she thinks fabs are all godless. But she heard somewhere that the air was the safest place in a war.” He pointed at the shredded ship. “Not as dangerous as down there.”

“That’s certain enough,” Deryn said, patting the airship’s humming skin. “Hey, look …

now

we’re going to get a show!”

The kraken tender was going to work.

Two spotlights stretched out from the

Gorgon

, flicking through signal colors as they swept across the water, calling up their beast. When the lights reached the schooner, they shifted to a dazzling white, illuminating the damage

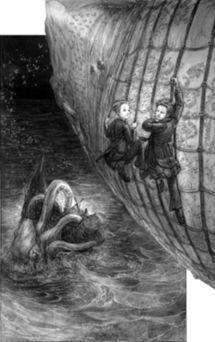

“A KRAKEN FINISHES THE JOB.”

the

Leviathan

’s bats had done. Hardly anything was left of the sails, and the rigging looked like a tangle of chewed-up shoelaces. The deck was covered with splinters and glittering spikes.

“Blisters!” Newkirk cried. “Look what we …”

His voice faded as the first arm of the beast rose from the water.

The huge tentacle swept through the air, a sheet of seawater spilling like rain from its length. The Royal Navy kraken was another of Huxley’s fabrications, Deryn had read, made from the life chains of the octopus and giant squid. Its arm uncoiled like a vast, slow whip in the spotlights.

Taking its time, the tentacle curled around the schooner, its suckers clamping tight against the hull. Then it was joined by another arm, and each took one end of the ship. The vessel snapped between them, the awful sound of tearing wood bouncing across the black water to Deryn’s ears.

More tentacles uncoiled from the water, wrapping around the ship. Finally the kraken’s head rose into view, one huge eye gazing up at the

Leviathan

for a moment before the beastie pulled the schooner beneath the waves.

Soon nothing but flotsam remained above the waves. The guns of the

Gorgon

roared in salute.

“Hmph,” Newkirk said. “I suppose that’s the ocean navy having the final word. Bum-rags.”

“I can’t say anyone on that schooner would have been bothered by that kraken,” Deryn said. “Being killed a second time doesn’t hurt much.”

“Aye, it was

us

who did the damage. Barking brilliant, we are!”

The first bats were already fluttering home, which meant it was time for the midshipmen to climb down to get more feed. Deryn flexed her tired muscles. She didn’t want to slip and wind up down there with the kraken. The beastie was probably annoyed that its breakfast hadn’t contained any tasty crewmen, and Deryn didn’t fancy improving its mood.

In fact, watching the fléchette strike had left her shaky. Maybe Newkirk was itching for battle, but she’d joined the Service to fly, not to shred some poor buggers a thousand feet below.

Surely the Germans and their Austrian chums weren’t so daft as to start a war just because some aristocrat had been assassinated. The Clankers were like Newkirk’s mum. They were afraid of fabricated species, and worshipped their mechanical engines. Did they think their mob of walking contraptions and buzzing aeroplanes could stand against the Darwinist might of Russia, France, and Britain?

Deryn Sharp shook her head, deciding that war talk was all a load of blether. The Clanker powers couldn’t possibly want to fight.

She turned from the scattered wreckage of the schooner and scrambled after Newkirk down the

Leviathan

’s trembling flank.

THIRTEEN

Walking through the town of Lienz, Alek’s skin began to crawl.

He’d seen markets like this before, full of bustle and the smells of slaughter and cooking. It might have been charming from an open-air walker or a carriage. But Alek had never visited such a place on foot before.

Steam carts rumbled down the streets, spitting hot clouds of vapor. They carried piles of coal, caged chickens screeching in chorus, and overloaded stacks of produce. Alek kept slipping on potatoes and onions that had spilled onto the cobblestones. Slabs of raw meat swung from long poles that men carried on their shoulders, and pack mules prodded Alek with their loads of sticks and firewood.

But worst of all were the people. In the walker’s small cabin he’d grown used to the smell of unwashed bodies. But here in Lienz hundreds of commoners packed the

“THE STREETS OF LIENZ.”

Saturday market, bumping into Alek from all directions and treading on his feet without a murmur of apology.

At every stall people yammered about prices, as if obliged to argue over every transaction. Those that weren’t bickering stood around discussing trivialities: the summer heat, the strawberry crop, or the health of someone’s pig.

Their constant chatter about nothing made a certain sense, he supposed, as nothing important ever happened to common people. But the sheer insignificance of it all was overwhelming.

“Are they always this way?” he asked Volger.

“What way, Alek?”

“So trivial in their conversation.” An old woman bumped him, then muttered a curse under her breath. “And rude.”

Volger laughed. “Most men’s awareness doesn’t extend past their dinner plates.”

Alek saw a sheet of newsprint fluttering underfoot, half ground into the mud by a carriage wheel. “But surely they know what happened to my parents. And that war is coming. Do you suppose they’re really quite anxious, and only pretending not to worry?”

“What I suppose, Your Highness, is that most of them cannot read.”

Alek frowned. Father had always given money to the Catholic schools, and supported the idea that every man should be given a vote, regardless of station. But listening to the prattle of the crowd, Alek doubted that commoners could possibly understand affairs of state.

“Here we are, gentlemen,” Klopp said.

The mechaniks shop was a solid-looking stone building on the edge of the market square. Its open door led into a cool, mercifully quiet darkness.

“Yes?” a voice called from the shadows. As Alek’s eyes adjusted, he saw a man staring up at them from a workbench cluttered with gears and springs. Larger mechaniks lined the walls—axles, pistons, one entire engine hulking in the gloom.

“Need a few parts, is all,” Klopp said.

The man looked them up and down, taking in the clothes they’d stolen from a farmer’s washing line a few days ago. All three of them were still coated with yesterday’s dirt and shredded rye.

The shopkeeper’s eyes dropped back to his work. “Not much in the way of farm mechaniks here. Try your luck at Kluge’s.”

“Here’s good enough,” Klopp said. He stepped forward and dropped a money purse onto the workbench. It struck the wood with a muffled

chunk

, its sides bulging with coins.

The man raised an eyebrow, then nodded.

Klopp began to list gears and glow plugs and electrikals, the parts of the Stormwalker that had begun to wear after a fortnight of travel. The shopkeeper interrupted with questions now and then, but never took his eyes from the money purse.

As he listened, Alek noticed that Master Klopp’s accent had changed. Normally, he spoke in a slow, clear cadence, but now his words blurred and trilled with a common drawl. For a moment Alek thought Klopp was pretending. But then he wondered if this was the man’s normal way of speaking. Maybe he put on an accent in front of nobles.

It was strange to think that in three years of training Alek had never heard his tutor’s true accent.

When the list was done, the shopkeeper nodded slowly. Then his eyes flicked to Alek. “And perhaps something for the boy?”

He pulled a toy from the clutter. It was a six-legged walker, a model of an eight-hundred-ton land frigate,

Mephisto

class. After winding its spring, the shopkeeper pulled the key from its back. The toy began to walk, jerkily pushing its way through the gears and screws.

The man glanced up, one eyebrow raised.

Two weeks ago Alek would have found the contraption fascinating, but now the jittering toy seemed childish. And it was insufferable that this commoner was calling him a

boy

.

He snorted at the tiny walker. “The pilothouse is all wrong. If that’s meant to be a

Mephisto

, it’s too far astern.”

The shopkeeper nodded slowly, leaning back with a smile. “Oh, you’re quite the young master, aren’t you? You’ll school me in mechaniks next, I suppose.”

Alek’s hand went instinctively to his side, where his sword would normally have hung. The man’s eyes tracked the gesture.

The room was dead silent for a moment.

Then Volger stepped forward and swept up the money purse. He pulled a gold coin out and slapped it down onto the workbench.

“You didn’t see us,” he said, his voice edged with steel.

The shopkeeper didn’t react, just stared at Alek, as if memorizing his face. Alek stared back at him, hand still on his imaginary sword, ready to issue a challenge. But suddenly Klopp was pulling him toward the door and back out onto the street.

As the dust and sunlight stung his eyes, Alek realized what he’d done. His accent, his bearing … The man had

seen

who he was.

“Perhaps our lesson in humility yesterday was insufficient,” Volger hissed as they pushed through the crowds, heading toward the stream that would lead back to the hidden walker.

“This is my fault, young master,” Klopp said. “I should have warned you not to speak.”

“He knew from the first word out of my mouth, didn’t he?” Alek said. “I’m a fool.”

“We’re all three fools.” Volger threw a silver coin at a butcher and snatched up two strings of sausages without stopping. “Of

course

they’ve warned the Guild of Mechaniks to look out for us!” He swore. “And we brought you straight into the first shop we found, thinking a bit of dirt would hide you.”

Alek bit his lip. Father had never allowed him to be photographed or even sketched, and now Alek knew why—in case he would ever need to hide. And yet he’d still given himself away. He’d heard the difference in Klopp’s speech. Why couldn’t he have kept his own mouth shut?

As they reached the edge of the market, Klopp pulled them to a halt, his nose in the air. “I smell kerosene. We need at least that, and motor oil, or we won’t get another kilometer.”

“Let’s be quick about it, then,” Volger said. “My bribe was probably worse than useless.” He shoved a coin into Alek’s hand and pointed. “See if you can buy a newspaper without starting a duel, Your Highness. We need to know if they’ve chosen a new heir yet, and how close Europe is to war.”

“But stay in sight, young master,” Klopp added.

The two men headed toward a stack of fuel cans, leaving Alek alone in the market’s crush. He pushed his way through the crowd, gritting his teeth against the jostling.

The newspapers were arrayed on a long bench, their pages weighted down with stones, corners fluttering in the breeze. He looked from one to the next, wondering which to choose. His father had always said that newspapers without pictures were the only ones worth reading.

His eyes fell on a headline: EUROPE’S SOLIDARITY AGAINST SERBIAN PROPAGANDA.

All the papers were like that, confident that the whole world supported Austria-Hungary after what had happened in Sarajevo. But Alek wondered if that were true. Even the people in this small Austrian town didn’t seem to care much about his parents’ murder.

“What’ll you have?” a voice demanded from the other side of the bench.

Alek looked at the coin in his hand. He’d never held money before, except for the Roman silver pieces in his father’s collection. This coin was gold, bearing the Hapsburg crest on one side and a portrait of Alek’s granduncle on the other—Emperor Franz Joseph. The man who had decreed that Alek would never take the throne.

“How many will this buy?” he asked, trying to sound common.

The newspaper man took the coin and eyed it closely. Then he slipped it into his pocket and smiled as though speaking to an idiot. “Many as you like.”

Alek started to demand a proper answer, but the words died on his tongue. Better to act like a fool than sound like a nobleman.

He swallowed his anger and filled his arms with one copy of every paper, even those plastered with photographs of racing horses and ladies’ salons. Perhaps Hoffman and Bauer would enjoy them.

As Alek glared at the newspaper man one last time, an unsettling realization overtook him. He spoke French, English, and Hungarian fluently, and always impressed his tutors in Latin and Greek. But Prince Aleksandar of Hohenberg could barely manage the daily language of his own people well enough to buy a newspaper.