Leviathan (3 page)

Authors: Scott Westerfeld

THREE

“Wake up, you ninny!”

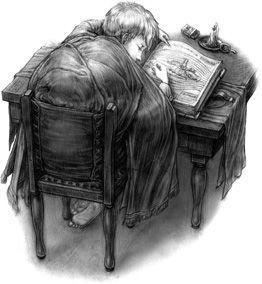

Deryn Sharp opened one eye … and found herself staring at etched lines streaming past an airbeast’s body, like a river’s course around an island—an airflow diagram. Lifting her head from the aeronautics manual, she discovered that the open page was stuck to her face.

“You stayed up all night!” The voice of her brother, Jaspert, battered her ears again. “I told you to get some sleep!”

Deryn gently peeled the page from her cheek and frowned—a smudge of drool had disfigured the diagram. She wondered if sleeping with her head in the manual had stuffed still more aeronautics into her brain.

“Obviously I

did

get some sleep, Jaspert, seeing as you found me snoring.”

“Aye, but not properly in bed.” He was moving around the small rented room in the darkness, piecing together a clean airman’s uniform. “One more hour of studying, you said, and you’ve burnt our last candle down to a squick!”

Deryn rubbed at her eyes, looking around the small, depressing room. It was always damp and smelled of horse clart from the stables below. Hopefully last night would be the last time she slept here, in bed or not. “Doesn’t matter. The Service has its own candles.”

“Aye, if you pass the test.”

Deryn snorted. She’d studied only because she hadn’t been able to sleep, half excited about finally taking the airman middy’s test, half terrified that someone would see through her disguise. “No need to worry about that, Jaspert. I’ll pass.”

Her brother nodded slowly, a mischievous expression crossing his face. “Aye, maybe you’re a crack hand with sextants and aerology. And maybe you can draw any airbeast in the fleet. But there’s one test I haven’t mentioned. It’s not about book learning—more what they call ‘air sense.’”

“Air sense?”

Deryn said. “Are you winding me up?”

“It’s a dark secret of the Service.” Jaspert leaned forward, his voice dropping to a whisper. “I’ve risked expulsion for daring to mention it to a civilian.”

“You are full of

clart

, Jaspert Sharp!”

“I can say no more.” He pulled his still-buttoned shirt over his head, and when his face emerged, it had broken into a smile.

Deryn scowled, still not sure if he was kidding. As if she weren’t nervous enough.

Jaspert tied his airman’s neckerchief. “Get your slops on and we’ll see what you look like. All that studying’s going to waste if your tailoring don’t persuade them.”

Deryn stared sullenly down at the pile of borrowed clothes. After all her studying and everything she’d learned when her father was alive, the middy’s test would be easy. But what was in her head wouldn’t matter unless she could fool the Air Service boffins into believing her name was Dylan, not Deryn.

She’d resewn Jaspert’s old clothes to alter their shape, and she was plenty tall—taller than most boys of midshipman’s age. But height and shape weren’t everything. A month of practicing on the streets of London and in front of the mirror had convinced her of that.

Boys had something else … a sort of

swagger

about them.

When she was dressed, Deryn gazed at her reflection in a darkened window. Her usual self stared back: female and fifteen. The careful tailoring only made her look queerly skinny, not so much a boy as some tattie bogle set out in old clothes to scare the crows.

“Well?” she said finally. “Do I pass as a Dylan?”

Jaspert’s eyes drifted up and down, but he said nothing.

“I’m plenty tall for sixteen, right?” she pleaded.

Finally he nodded. “Aye, I suppose you’ll pass. It’s just lucky you’ve no diddies to speak of.”

Deryn’s jaw dropped open, her arms crossing over her chest. “And you’re a bum-rag covered in clart!”

Jaspert laughed, slapping her hard on the back. “That’s the spirit. I’ll have you swearing like a navy lad yet.”

The London omnibuses were much fancier than those back in Scotland—faster, too. The one that took them to the airship field at Wormwood Scrubs was drawn by a hippoesque the breadth of two oxen across the shoulders. The huge, powerful beast had them nearing the Scrubs before dawn had broken.

Deryn stared out the window, watching the movements of treetops and windblown trash for hints about the day’s weather. The horizon was red, and the

Manual of Aerology

claimed,

Red sky in morning, sailors take warning

. But Da had always said that was just an old wives’ tale. It was when you saw a dog eating grass that you knew the heavens were about to split.

Not that a drop of rain mattered—the tests today would be indoors. It was book learning the Air Service demanded from their young midshipmen: navigation and aerodynamics. But staring at the sky was safer than reading the glances of the other passengers.

Since getting on the bus with Jaspert, Deryn’s skin had itched with wondering what she looked like to strangers. Could they see through her boy’s slops and shorn hair? Did they really think she was a young recruit on his way to the Air Proving Ground? Or did she look like some lassie with a few screws loose, playing dress-up in her brother’s old clothes?

The omnibus’s next to last stop was at the Scrubs’ famous prison. Most of the passengers disembarked there, women carrying lunch pails and gifts for their men inside. The sight of barred windows made Deryn’s stomach churn. How much trouble would Jaspert be in if this ruse went wrong? Enough to lose his position in the Service? To send him to jail, even?

It just wasn’t

fair

, her being born a girl! She knew more about aeronautics than Da had ever crammed into Jaspert’s attic. On top of which, she had a better head for heights than her brother.

The worst thing was, if the boffins didn’t let her into the Service, she’d be spending tonight in that horrible rented room again, and headed back to Scotland by tomorrow.

Her mother and the aunties were waiting there, certain that this mad scheme wouldn’t work and ready to stuff Deryn back into skirts and corsets. No more dreams of flying, no more studying, no more

swearing

! And the last of her inheritance wasted on this trip to London.

She glared at the three boys riding in the front of the bus, jostling each other and giggling nervously as the proving ground drew closer, happy as a box of birds. The tallest hardly came up to Deryn’s shoulder. They couldn’t be so much stronger, and she didn’t credit that they were as smart or as brave. So why should

they

be allowed into the king’s service and not her?

Deryn Sharp gritted her teeth, resolving that no one would see through her disguise.

There couldn’t be

that

much trick to it, being a stupid boy.

The line of recruits on the ascension field weren’t impressive. Most looked barely sixteen, sent off by their families to find fortune and advancement. A few older boys were mixed in with the others, probably middies coming over from the navy.

Looking at their anxious faces, Deryn was glad to have had a father who’d taken her up in hot-air balloons. She’d seen the ground from on high plenty of times. But that didn’t keep her nerves from playing up. She almost reached for Jaspert’s hand before realizing how

that

would look.

“All right,

Dylan

,” he said quietly as they neared the desk. “Just remember what I told you.”

Deryn snorted. Last night Jaspert had demonstrated how a proper boy checked his fingernails—looking at his palm, fingers bent, whereas girls looked at the backs of their hands, fingers splayed.

“Aye, Jaspert,” she said. “But if they ask me to do my nails, don’t you think the jig’s up already?”

He didn’t laugh. “Just don’t draw attention to yourself, right?”

Deryn said nothing more, following him to the long table set up outside a white hangar tent. Three officers sat behind it, accepting letters of introduction from the recruits.

“Ah, Coxswain Sharp!” one said. He wore the uniform of a flight lieutenant, but also the curve-brimmed bowler hat of a boffin.

Jaspert saluted him smartly. “Lieutenant Cook, may I present my cousin Dylan.”

When Cook held out his hand to Deryn, she felt the moment of British pride that boffins always gave her. Here was a man who’d reached into the very chains of life and worked them to suit his purposes.

She gave his hand the firmest shake she could. “Nice to meet you, sir.”

“Always a pleasure to meet a Sharp fellow,” the boffin said, then chuckled at his own joke. “Your cousin speaks highly of your comprehension of aeronautics and aerology.”

Deryn cleared her throat, using the soft, low voice she’d been practicing for weeks. “My da—that is, my uncle—taught us all about ballooning.”

“Ah, yes, a brave man.” He shook his head. “A tragedy he isn’t here to see the triumphs of living flight.”

“Aye, he would’ve loved it, sir.” Da had gone up in only hot-air balloons, not hydrogen breathers like the Service used.

Jaspert gave her a nudge, and Deryn remembered the letter of recommendation. She pulled it from her jacket and offered it to Flight Lieutenant Cook. He pretended to study it, which was silly because he’d written it himself as a favor to Jaspert, but even boffins had to follow Royal Navy form.

“This seems to be in order.” His eyes drifted up from the letter and traveled across Deryn’s borrowed outfit, looking troubled for a moment by what he saw.

She stood stiffly under his gaze, wondering what she’d done wrong. Was it her hair? Her voice? Had the handshake somehow gone amiss?

“Bit spindly, aren’t you?” the boffin finally said.

“Aye, sir. I suppose so.”

His face broke into a smile. “Well, we had to fatten up your cousin too. Mr. Sharp, please join the line!”

FOUR

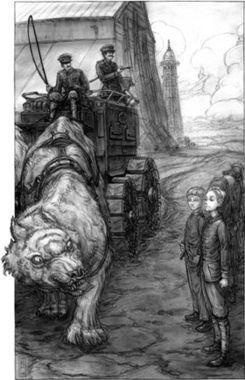

The sun was just starting to creep above the tree line when the proper military men arrived. They rolled across the field in an all-terrain carriage drawn by two lupine tigeresques, pulling up smartly before the line of recruits. The beasts’ muscles bulged under the leather straps of the carriage rig, and when one shook itself like a monstrous house cat, sweat flew in all directions.

In the corners of her vision Deryn saw the boys around her stiffen. Then the carriage driver set the tigers growling with a snap of his whip, and a nervous murmur traveled down the line.

A man in a flight captain’s uniform stood in the open carriage, a riding crop under one arm. “Gentlemen, welcome to Wormwood Scrubs. I trust none of you is frightened by the fabrications of natural philosophy?”

No one answered. Fabricated beasts were everywhere

“ADDRESSING THE APPLICANTS.”

in London, of course, but nothing so magnificent as these half-wolf tigers, all sinews and claws, a crafty intelligence lurking in their eyes.

Deryn kept her eyes forward, though she was dying to take a closer look at the tigeresques. Before today she’d seen military fabs only in the zoo.

“Barking spiders!” the young boy next to her whispered. He was nearly as tall as her, and his short blond hair stuck straight up into the air. “I’d hate to see those two get loose.”

Deryn resisted the urge to explain that lupines were the tamest of the fabs. Wolves were really just a kind of dog, and could be trained almost as easily. Airbeasts came from trickier stock, of course.

When no one stepped forward to admit their fear, the flight captain said, “Excellent. Then you won’t mind a closer look.”

The driver’s whip snapped again, and the carriage rumbled across the broken field, the nearest tiger passing within arm’s reach of the volunteers. The snarling beasts were too much for three boys at the other end of the line. They broke ranks and ran shrieking back toward the open gates of the Scrubs.

Deryn kept her eyes focused directly ahead as the tigers passed, but a whiff of them—a mix of wet dog and raw meat—sent shivers down her spine.

“Not bad, not bad,” the flight captain said. “I’m glad to see so few of our young men succumbing to common superstition.”

Deryn snorted. A few people—Monkey Luddites, they were called—were afraid of Darwinist beasties on principle. They thought that crossbreeding natural creatures was more blasphemy than science, even if fabs had been the backbone of the British Empire for the last fifty years.

She wondered for a moment if these tigers were the secret test Jaspert had warned her about, and smirked. If so, it had been a pure dawdle.

“But your nerves of steel may not last the day, gentlemen,” the flight captain said. “Before moving on we’d like to discover if you have a head for heights. Coxswain?”

“About-

face

!” shouted an airman. With a muddled bit of shuffling, the line of boys turned itself about to face the hangar tent. Deryn saw that Jaspert was still here, hanging off to one side with the boffins. They were all wearing clart-snaffling grins.

Then the hangar’s tent flaps split apart, and Deryn’s jaw dropped open… .

An airbeast was inside: a Huxley ascender, its tentacles in the grips of a dozen ground men. The beast pulsed and trembled as they drew it gently out, setting its translucent gasbag shimmering with the red light of the rising sun.

“A medusa,” gasped the boy next to her.

Deryn nodded. This was the first hydrogen breather ever fabricated, nothing like the giant living airships of today, with their gondolas, engines, and observation decks.

The Huxley was made from the life chains of medusae— jellyfish and other venomous sea creatures—and was practically as dangerous. One wrong puff of wind could spook a Huxley, sending it diving for the ground like a bird headed for worms. The creatures’ fishy guts could survive almost any fall, but their human passengers were rarely so lucky.

Then Deryn saw a pilot’s rig hanging from the airbeast, and her eyes widened still farther.

Was this the test of “air sense” Jaspert had been hinting at? And he’d let her believe he’d only been kidding!

That bum-rag

.

“You lucky young gents will be taking a ride this morning,” the flight captain said from behind them. “Not a long one: only up a thousand feet or so and then back down … after ten minutes lofting in the air. Believe me, you’ll see London as you never have before!”

Deryn felt a smile creeping across her lips. Finally, a chance to see the world from on high again, just like in one of Da’s balloons.

“To those of you who’d prefer not to,” the flight captain finished, “we bid fond farewells.”

“Any of you little blighters want out?” shouted the coxswain from the end of the line. “Then get out

now

! Otherwise, it’s skyward with you!”

After a short pause another dozen boys departed. They didn’t run screaming this time, just slunk toward the gates in a huddled pack, a few pale and frightened faces glancing back at the pulsing, hovering monster. Deryn realized with pride that almost half the volunteers were gone.

“Right, then.” The flight captain stepped in front of the line. “Now that the Monkey Luddites have been cleared out, who’d like to go first?”

Without hesitation, without a thought of what Jaspert had said about not drawing attention, and with the last squick of nerves in her belly gone, Deryn Sharp took one step forward.

“Please, sir. I’d like to fly.”

The pilot’s rig held her snugly, the contraption swaying gently under the medusa’s body. Leather straps passed under her arms and around her waist, then were clipped to the curved seat that she perched on like a horseman riding sidesaddle. Deryn had worried that the coxswain would discover her secret as he buckled her in, but Jaspert had been right about one thing: There wasn’t much to give her away.

“Just ride it up, laddie,” the man said quietly. “Enjoy the view and wait for us to pull you down. Most of all, don’t do

anything

to upset the beastie.”

“Aye, sir.” She swallowed.

“If you start to panic, or if you think something’s gone wrong, just throw this.” He pressed a thick roll of yellow cloth into her hand, then tied one end around her wrist. “And we’ll wind you down steady and fast.”

Deryn clutched it tightly. “Don’t worry. I won’t panic.”

“That’s what they all say.” He smiled, and pressed into her other hand a cord leading to a pair of water bags harnessed to the creature’s tentacles. “But if by any chance you do anything

completely

stupid, the Huxley may go into a dive. If the ground’s coming up too fast, just give this a tug.”

“It spills the water out, making the beast lighter,” Deryn said, nodding. Just like the sandbags on Da’s balloons.

“Very clever, laddie,” the coxswain said. “But cleverness is no substitute for air sense, which is Service talk for

keeping your barking head

. Understand?”

“Yes,

sir

,” Deryn said. She couldn’t wait to get off the ground, the flightless years since Da’s accident suddenly heavy in her chest.

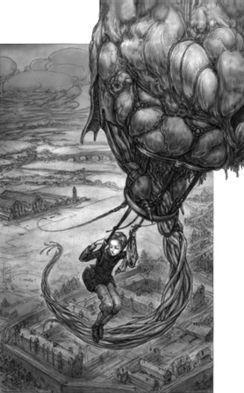

The coxswain stepped back and blew a short pattern on his whistle. As the final note shrieked, the ground men let go of the Huxley’s tentacles all together.

The straps cut into her as the airbeast rose, like being scooped up in a giant net. A moment later the feeling of ascent vanished, as if the earth itself were dropping away… .

Down below, the line of boys stared up in undisguised

“ASCENDING.”

awe. Jaspert was grinning like a loon, and even the boffins’ faces showed squicks of fascination. Deryn felt brilliant, rising through the air at the center of everyone’s attention, like an acrobat aloft on a swing. She wanted to make a speech:

“Hey, all you sods, I can fly and you can’t! A natural airman, in case you haven’t noticed. And in conclusion, I’d like to add that I’m a girl and you can all get stuffed!”

The four airmen at the winch were letting the cable out quickly, and soon the upturned faces blurred with distance. Larger geometries came into view: the worn curves of an old cricket oval on the ascension field, the network of roads and railways surrounding the Scrubs, the wings of the prison pointing southward like a huge pitchfork.

Deryn looked up and saw the medusa’s body alight with the sunrise, pulsing veins and arteries running like iridescent ivy through its translucent flesh. The tentacles drifted in the soft breezes around her, capturing pollen and insects and sucking them into the stomach sack above.

Hydrogen breathers didn’t really breathe hydrogen, of course. They

exhaled

it: burped it into their own gasbags. The bacteria in their stomachs broke down food into pure elements—oxygen, carbon, and, most important, lighter-than-air hydrogen.

It should have been nauseating, Deryn supposed, hanging suspended from all those gaseous dead insects. Or terrifying, with nothing but a few leather straps between her and a quarter mile of tumbling to a terrible death. But she felt as grand as an eagle on the wing.

The smoky outline of central London rose up toward the east, divided by the winding, shimmering snake of the River Thames. Soon she could make out the green expanse of Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens. It was like looking down on a living map: the omnibuses crawling along like bugs, sailboats fluttering as they tacked against the breeze.

Then, just as the spire of St. Paul’s Cathedral rose into view, a shiver passed through the rig.

Deryn scowled. Were her ten minutes up

already

?

She looked down, but the line leading to the ground hung slack. They weren’t reeling her in just yet.

The jolt came again, and Deryn saw a few of the tentacles around her clench, coiling like ribbons scraped between a pair of scissors. They were slowly gathering back into a single strand.

The Huxley was nervous.

Deryn swung herself from side to side, ignoring the majesty of London to search the horizon for whatever was spooking the airbeast.

Then she spotted it: a dark shapeless mass in the north, a rolling wave of clouds spreading across the sky. Its leading edge crept forward steadily, blackening the northern suburbs with rain.

Deryn felt the hairs on her arms tingling.

She dropped her gaze to the Scrubs, wondering if the tiny airmen down there could see the storm front too, and would start to reel her in. But the proving ground still glowed with light from the rising sun. From down there they would see only clear skies above, as cheery as a picnic.

Deryn waved a hand. Could they even see her well enough? But of course they’d only think she was larking about.

“Bum-rag!” she swore, and glared at the roll of yellow cloth tied to her wrist. A real ascender scout would have semaphore flags, or at least a message lizard that could scamper down the line. But all they’d given her was a panic signal.

And Deryn Sharp was

not

panicking!

At least, she didn’t think she was… .

She stared at the blackness in the sky, wondering if it were only a last bit of night the sunrise hadn’t chased away. What if she had no air sense at all, and the height had gone to her head?

Deryn closed her eyes, took a deep breath, and counted to ten.

When she opened them again, the clouds were still there—closer.

The Huxley trembled again, and Deryn smelled lightning in the air. The approaching squall was definitely real. The aerology manual had been right after all:

Red sky in morning, sailors take warning.

She stared again at the yellow cloth. If the officers below saw it unfurl, they’d think she was panicking. Then she’d have to explain that it hadn’t been terror, just a coolheaded observation that rough weather was coming. Maybe they’d commend her for making the right decision.

But what if the squall changed course? Or faded to a drizzle before it arrived at the Scrubs?

Deryn clenched her teeth, wondering how long she’d been up here. Weren’t ten minutes almost up? Or had her sense of time gone crook in the vast, cold sky?

Her eyes darted back and forth between the rolled-up yellow cloth and the approaching storm, wondering what a

boy

would do.