Liesl & Po (15 page)

Authors: Lauren Oliver

Bundle went,

Mwark

.

At that moment the train began to slow; the lurching began to lessen. A sign flashed briefly in the darkness. It read

CLOVERSTOWN, 2 MILES

.

“Yes.” Liesl gripped the windowsill tightly, keeping her eyes on those leaping chimneys of flame and trying not to think of the safety and the closeness of the attic. “That is our stop.”

Will had balled up his jacket to serve as a makeshift pillow and had slept most of the night with his head resting against the window. He woke up as the train was drawing into a station.

The conductor moved through the aisles, ringing a bell, bellowing, “Cloverstown! First stop, Cloverstown! This is Cloverstown!”

“He doesn’t have to shout,” someone muttered. Will started. He had not seen anyone sit down. An old woman, working a finger irritably in one ear and tapping her steel-tipped cane agitatedly, was seated across the aisle from him, next to an enormous police officer who continued to sleep, head to chest, snoring.

Will turned back to the window. He knew of Cloverstown. It was a factory and mining town. In the hills that surrounded it were the mines, where boys from the orphanage who had not found families or employment were ultimately sent, to work forever underground in those dark and terrible tunnels, burrowing like insects and living with the constant crushing fear of all that stone and earth over their heads, ready to come crashing down.

The girls went to work in the Cloverstown factories, sewing day in and day out, stitching cheap linens and hat linings until their eyes gave out and they went blind, or stirring large vats of poisonous chemicals until, one day, their minds went as soft as cheese that has been left too long in the heat. The end result was always the same: They ended up beggars, endlessly walking the filthy, teeming streets, begging money from people hardly richer or better off than they were.

For the first time, as Will stared at the awful black buildings—so coated with coal dust they looked like they’d been crafted from smoke—and heard the roar of the furnaces, he began to question his decision to leave the alchemist’s. At least at the alchemist’s he had had food (most of the time) and a roof over his head. He thought about the boys who had gone into the mines. He thought about the way they had shivered when the cart came to retrieve them from the orphanage, and the look of their sad, pale, defeated faces, as though they were already ghosts.

“Cloverstown! Cloverstown! First stop, Cloverstown! Next stop, Howard’s Glen!”

“Enough to take your ear off,” the old woman muttered, this time working her finger in her other ear.

Well, he would most certainly not get off in Cloverstown. He would keep going, he decided. He would go all the way north, to the last stop. Perhaps he could build a snow hut and live in it for a time.

And then the unthinkable, the unbelievable, the impossible happened: As Will was staring at the grimy Cloverstown station, the girl from the attic passed under-neath his window, walking neatly and deliberately down the platform, carrying a small wooden box.

Will let out a cry of surprise and jumped up from his seat.

“It’s her!” He was filled with such a tremendous, tumbling sense of joy he could not help but exclaim out loud, to no one in particular. “It’s the girl in the attic. Only she’s not in the attic anymore. She’s here. Or, um, there.”

“What are you babbling on about now?” demanded the old woman irritably, thinking that no one had the decency to speak at a normal volume. But she stumped to her feet and leaned toward the window to see what the scraggly boy was so excited about.

Liesl had at that moment paused outside to get her bearings, and as she turned and looked around her, both Will and the old woman, staring down, got a nice long look at her face. Will thought,

Angel

, precisely as the old woman thought,

Devil

, and let out a wicked howl.

(That is the strangest thing about the world: how it looks so different from every point of view.)

“It’s her!” the old woman screeched. “The batty one!” She prodded the policeman forcefully awake with her cane. “Come on, now. Move it.”

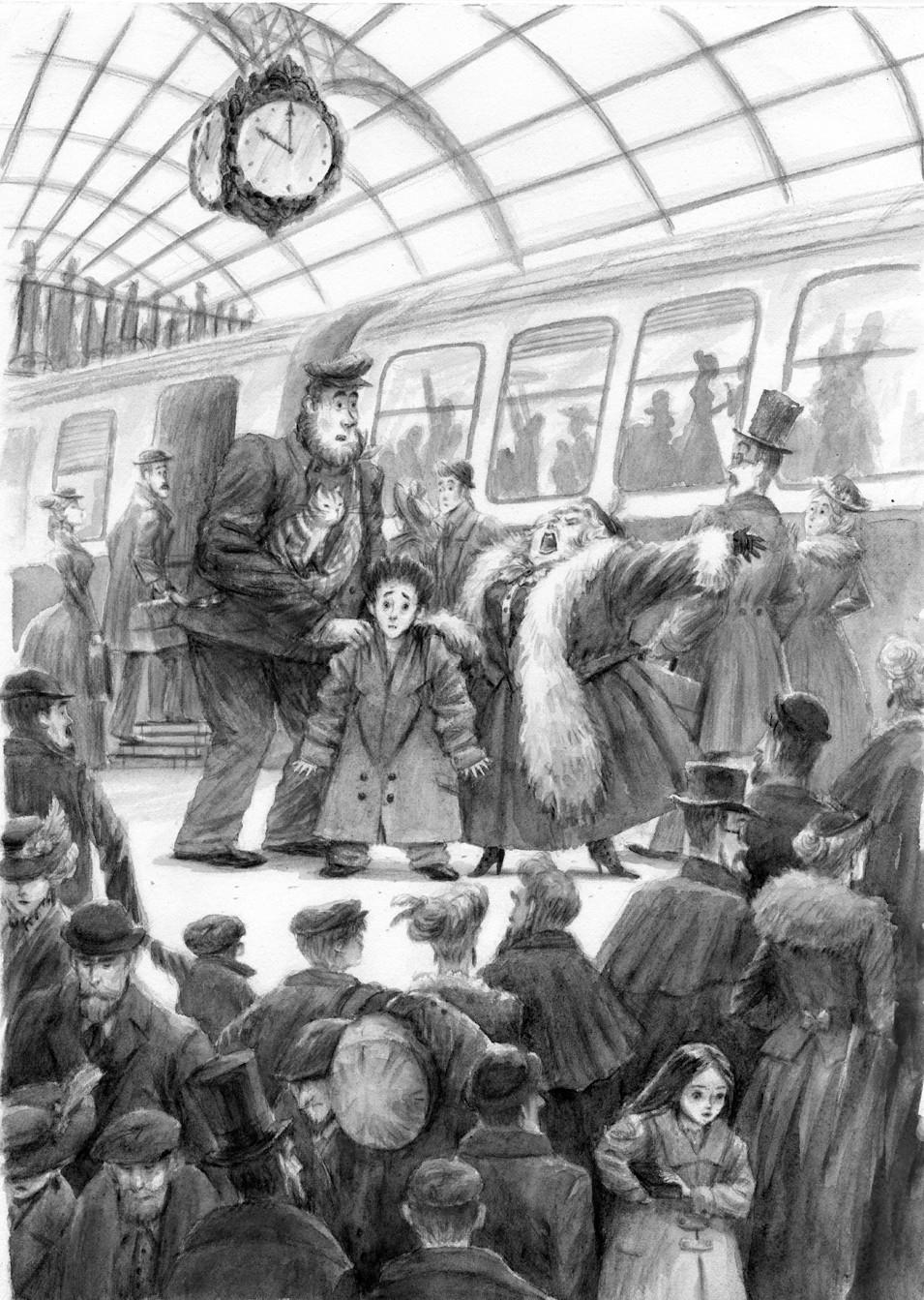

Will had already darted around her and was pushing his way toward the door, threading past the other passengers who were disembarking. His heart pounded painfully in his ribs. It was a sign! She was a sign—a sign he had made the right decision. He must, he absolutely must, find her.

The old woman and the police officer came clomping along behind him, but he took no notice of them.

“Excuse me, excuse me.” He ducked past a frail man carrying an empty birdcage and burst onto the platform.

The spot where Liesl had been standing was empty. She was gone.

For a second his heart dived all the way to his toes. He had lost her. But then he caught a glimpse of a dark purple coat and a bit of straight brown hair, a little ways farther down the platform. Instantly he set out at a run.

“Wait!” he called out. “Wait, please! Wait for me!” He wished more than anything, now, he had had the courage to ask for her name. He began calling out all the girls’ names he had thought of for her over the past thirteen months, hoping that one of them would be correct. “Rebecca! Katharine! Francine! Eliza! Laura!”

But she kept walking.

Dimly he was aware of the loud clattering of a cane behind him, and heavy footsteps, and a confusion of voices—one high and shrill and demanding, one a low growl—but he could think of nothing but the small figure in front of him.

And finally, when he was no more than ten feet away from her, he burst out, “You! The girl from the attic! Wait.”

She stopped walking right away. He stopped running only a few feet away from her. He stood there, panting in the thick and smoke-clotted air, while the girl from the attic turned around—slowly, so slowly, it seemed to him. In the time it took her to turn around, he had time to think of all the things she might do when she saw him there. Her face would light up. She would say, “You—the boy from the street corner.” Or somehow, miraculously (for she was a miracle to him; her presence there, on the platform, was proof), she would know his name, and she would greet him by it. “Hello, Will,” or “Hi, Will,” she would say.

But Liesl did none of those things.

Liesl turned, and saw a strange boy she had never seen before, red faced and panting; and behind him, she saw the old woman who had pretended to be on her way to get a hot potato muffin when really she had gone for the policeman; and behind

her

, she saw the policeman with his sharp silver handcuffs in his hand. Her mind went

click-click-whirr

, and she thought,

Boywomanpoliceman

, one unit.

In her ear, Po spoke the word, “Run.”

And so she turned and ran. She threw herself headfirst into the crowd, darting past fat women and squat children and men with dirty faces. She bumped up against a soft belly and heard a very quiet meow. She had collided with a man in a guard’s uniform, carrying a cat in a small sling.

“Excuse me,” Liesl said, always mindful of her manners. Then she took off running again.

The guard, who had managed to intercept train 128 thanks to an express train and a well-timed coach, and was standing on the platform waiting to board, took no notice of her. He was holding a hat, and staring determinedly at the small pink-eared boy who had just had his deepest dreams bashed to pieces.

Will was so distressed by Liesl’s horrified reaction—so different from what he had imagined!—he did not immediately have the heart to pursue her. What, he wondered, had he done? What could have caused her to have so violent a reaction? Was it his hair? Had he yelled too loudly? Or perhaps (he cupped a hand in front of his mouth and sniffed) the potato breath?

The old woman clomped up behind him and dug her nails sharply into Will’s shoulder.

“Where is she?” she demanded. She, too, was panting. “Where has she run off to?”

“What?” Will was still too devastated, and dazed, to think clearly. For over a year he had prayed to speak to the girl in the attic, and finally he had spoken to her, and she had run away! It was a cruel joke.

“The girl.” The woman narrowed her squinty eyes at him, until they were no more than two brown-colored peas settled neatly inside the wrinkles. “Your little friend. The nutty one.”

“She isn’t nutty,” Will said automatically, but immediately he began to have doubts. He didn’t really know anything about her . . . and that

would

explain the running off. . . .

“She’s as nutty as an acorn,” the old woman scoffed. “She’s as batty as a belfry! She’s a public menace, and she needs to be locked up!” The old woman stared pointedly at the police officer next to her, who grunted in agreement. Will noticed, uneasily, that the police officer was holding a pair of handcuffs.

“I—I don’t know anything about an acorn,” Will said nervously. He tried to back away, but the old woman kept her hand on his shoulder. Her nails dug into his skin.

“You will lead us to her,” she said, leaning closer, so he could see her yellow teeth very clearly. “It is your duty. It is for the Public Good.”

“I—,” Will started to protest, when a heavy hand clamped down on his

other

shoulder. Turning, he let out a squeal of disbelief, and the words died in his throat.

It was the guard from the Lady Premiere’s house.

“There you are,” Mo said cheerfully. “I had to follow you all the way from Dirge. You’re a pretty slippery thing, you know that?”

Will tried to speak, but only managed to gurgle.

“Had to take the express,” Mo continued, unaware that beneath his hand, Will had started to tremble violently. “Made it just by the skin of my coattails. I was just about to pop onboard when I looked around and saw you. Funny, isn’t it?” Mo chuckled to himself.

“Excuse me,” the old woman said witheringly. “I was having a conversation with this boy, and you have barged right into it.”

“I beg your pardon, ma’am.” Mo swept off his hat and performed a little bow, all the time keeping his hand on Will’s shoulder. “My name is Mo, and I am at your service.” As he tipped forward, Lefty peeked his head out of the sling strapped around Mo’s chest and let out a small meow.

The old woman shrieked. “What is that filthy animal doing on your—on your—” The rest of her words were swallowed by an enormous

“ACHOO!”

“Lefty’s not filthy,” Mo said reproachfully. As he spoke, he tugged Will closer to him. “Might have a bit of sardine breath, of course, but other than that she’s clean as a whistle.”

“All cats are—

ACHOO!

—filthy.” The old woman tugged Will back toward her side. “And I am deeply—

ACHOO!

—allergic, and demand that you—

ACHOO!

—get rid of that animal at once.”

Tug. Will went back to Mo’s side.

“With no disrespect, ma’am, I’d ask you whether

you’ve

had your bath today. Lefty has already had two.”

Tug. Back to the old woman.

“If my ‘bath’ consisted of—

ACHOO!

—licking myself from head to toe to—to—to—

ACHOO!

—tail, we might be glad that I had not—

ACHOO!

—taken it!”

Lefty seemed to be quite enjoying the argument about her cleanliness. Her tail, which protruded from the sling, was whipping merrily back and forth.

Will, sensing his opportunity to escape, sent a quick, silent apology the cat’s way—

Sorry, girl, this might pinch for a minute

—reached out, grabbed the cat’s tail, and squeezed as hard as he could.

Lefty let out a mighty yelp and jumped clear out of the sling on Mo’s chest.

For a second she hung, suspended, in the air.

Then the cat landed, right on the middle of the old woman’s sizable and sloping chest, and began scrabbling desperately to hang on.

Both the old woman and Mo released Will immediately.

The old woman let out a shriek that even Liesl, who had already left the train station and was winding her way through the dark and littered streets of Cloverstown, could hear.

“Get this beast—

ACHOO!

—off me!” she was scream-ing, as she danced around frantically, trying to use her cane to pry the cat from her chest. The harder she writhed and the more she twisted and turned, the harder Lefty clung to her chest. “Get the little monster—

ACHOO!

—off! It’s clawing me!”

“Just stay still, won’t you! I can’t get ’er if you aren’t still!” Mo was saying. “If you’d only stop

moving

for a second.”

The policeman stood there dumbly, scratching his head.

And once again, Will ran.

“Hey,” the policeman said glumly, watching the small boy dart into the crowd. “Hey. The boy is getting away.”

But neither Mo nor the old woman paid him any attention. She was shrieking and dancing; Mo was trying to reason with her; Lefty had just started to bite at one of her earrings.

So the policeman shrugged, yawned, and went off in search of a nice potato doughnut. It had, after all, been a very long night.