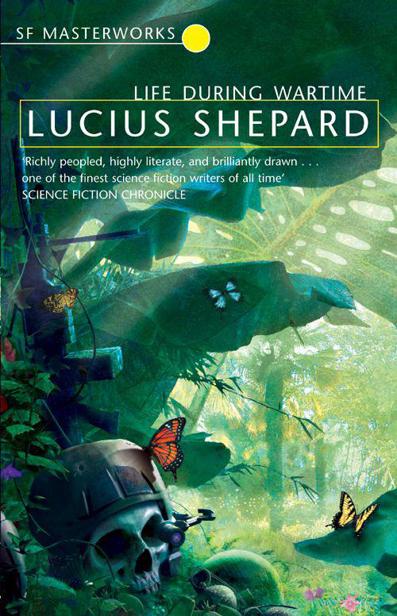

Life During Wartime

For Terry Carr

I’d like to acknowledge the support and friendship of the following during the writing of this book: Gardner Dozois, Susan Caspar, Lori Houck, Craig Spector, Jack and Jeanne Dann, Jim Kelly, John Kessel, Kim Stanley Robinson, Greg and Jane Smith, Beth Meacham, Tappan King, and ‘Shorty.’

Always the same story

Four Romans dead, and five Carthaginians …

–

Federico García Lorca

One of the new Sikorsky gunships, an element of the First Air Cavalry with the words

Whispering Death

painted on its side, gave Mingolla and Gilbey and Baylor a lift from the Ant Farm to San Francisco de Juticlan, a small town located inside the green zone, which on the latest maps was designated Free Occupied Guatemala. To the east of this green zone lay an undesignated band of yellow that crossed the country from the Mexican border to the Caribbean. The Ant Farm was a firebase on the eastern edge of the yellow band, and it was from there that Mingolla – an artillery specialist not yet twenty-one years old – lobbed shells into an area that the maps depicted in black-and-white terrain markings. And thus it was that he often thought of himself as engaged in a struggle to keep the world safe for primary colors.

Mingolla and his buddies could have taken their R and R in Rio or Caracas, but they had noticed that the men who visited these cities had a tendency to grow careless upon their return; they understood from this that the more exuberant your R and R, the more likely you were to end up a casualty, and so they always opted for the lesser distractions of the Guatemalan towns. They were not really friends; they had little in common, and under different circumstances they might well have been enemies. But taking their R and R together had come to be a ritual of survival, and once they had reached the town of their choice, they would go their separate ways and perform further rituals. Because the three had survived so much already, they believed that if they continued to perform these same rituals they would complete their tours unscathed. They had never acknowledged their belief to one another, speaking of it only obliquely – that, too, was part

of the ritual – and had this belief been challenged they would have admitted its irrationality; yet they would also have pointed out that the strange character of the war acted to enforce it.

The gunship set down at an airbase a mile west of town, a concrete strip penned in on three sides by barracks and offices, with the jungle rising behind them. At the center of the strip another Sikorsky was practicing takeoffs and landings – a drunken, camouflage-colored dragonfly – and two others were hovering overhead like anxious parents. As Mingolla jumped out, a hot breeze fluttered his shirt. He was wearing civvies for the first time in weeks, and they felt flimsy compared to his combat gear; he glanced around nervously, half-expecting an unseen enemy to take advantage of his exposure. Some mechanics were lounging in the shade of a chopper whose cockpit had been destroyed, leaving fanglike shards of plastic curving from the charred metal. Dusty jeeps trundled back and forth between the buildings; a brace of crisply starched lieutenants was making a brisk beeline toward a forklift stacked high with aluminum coffins. Afternoon sunlight fired dazzles on the seams and handles of the coffins, and through the heat haze the distant line of barracks shifted like waves in a troubled olive-drab sea. The incongruity of the scene – its what’s-wrong-with-this-picture mix of the horrid and the commonplace – wrenched at Mingolla. His left hand trembled, and the light seemed to grow brighter, making him weak and vague. He leaned against the Sikorsky’s rocket pod to steady himself. Far above, contrails were fraying in the deep blue range of the sky: XL-16s off to blow holes in Nicaragua. He stared after them with something akin to longing, listening for their engines, but heard only the spacy whisper of the Sikorsky’s.

Gilbey hopped down from the hatch that led to the computer deck behind the cockpit; he brushed imaginary dirt from his jeans, sauntered over to Mingolla, and stood with hands on hips: a short muscular kid whose blond crewcut and petulant mouth gave him the look of a grumpy child. Baylor stuck his head out of the hatch and worriedly scanned the horizon. Then he, too, hopped down. He was tall and rawboned, a couple of years older than Mingolla, with lank black hair and pimply olive skin and features so sharp

that they appeared to have been hatcheted into shape. He rested a hand on the side of the Sikorsky, but almost instantly, noticing that he was touching the flaming letter W in

Whispering Death, he

jerked the hand away as if he’d been scorched. Three days before there had been an all-out assault on the Ant Farm, and Baylor had not recovered from it. Neither had Mingolla. It was hard to tell whether Gilbey had been affected.

One of the Sikorsky’s pilots cracked the cockpit door. ‘Y’all can catch a ride into Frisco at the PX,’ he said, his voice muffled by the black bubble of his visor. The sun shone a white blaze on the visor, making it seem that the helmet contained night and a single star.

‘Where’s the PX?’ asked Gilbey.

The pilot said something too muffled to be understood.

‘What?’ said Gilbey.

Again the pilot’s response was muffled, and Gilbey became angry. ‘Take that damn thing off!’ he said.

‘This?’ The pilot pointed to his visor. ‘What for?’

‘So I can hear what the hell you saying.’

‘You can hear now, can’tcha?’

‘Okay,’ said Gilbey, his voice tight. ‘Where’s the goddamn PX?’

The pilot’s reply was unintelligible; his faceless mask regarded Gilbey with inscrutable intent.

Gilbey balled up his fists. ‘Take that son of a bitch off!’

‘Can’t do it, soldier,’ said the second pilot, leaning over so that the two black bubbles were nearly side by side. ‘These here doobies’ – he tapped his visor – ‘they got microcircuits that beams shit into our eyes. ’Fects the optic nerve. Makes it so we can see the beaners even when they undercover. Longer we wear ’em, the better we see.’

Baylor laughed edgily, and Gilbey said, ‘Bullshit!’ Mingolla naturally assumed that the pilots were putting Gilbey on, or else their reluctance to remove the helmets stemmed from a superstition, perhaps from a deluded belief that the visors actually did bestow special powers. But given a war in which combat drugs were issued and psychics predicted enemy movements, anything was possible, even microcircuits that enhanced vision.

‘You don’t wanna see us, nohow,’ said the first pilot. ‘The beams fuck up our faces. We’re deformed-lookin’ mothers.’

‘Course you might not notice the changes,’ said the second pilot. ‘Lotsa people don’t. But if you did, it’d mess you up.’

Imagining the pilots’ deformities sent a sick chill mounting from Mingolla’s stomach. Gilbey, however, wasn’t buying it. ‘You think I’m stupid?’ he shouted, his neck reddening.

‘Naw,’ said the first pilot. ‘We can see you ain’t stupid. We can see lotsa shit other people can’t, ’cause of the beams.’

‘All kindsa weird stuff,’ chipped in the second pilot. ‘Like souls.’

‘Ghosts.’

‘Even the future.’

‘The future’s our best thing,’ said the first pilot. ‘You guys wanna know what’s ahead, we’ll tell you.’

They nodded in unison, the blaze of sunlight sliding across both visors: two evil robots responding to the same program.

Gilbey lunged for the cockpit door. The first pilot slammed it shut, and Gilbey pounded on the plastic, screaming curses. The second pilot flipped a switch on the control console, and a moment later his amplified voice boomed out, ‘Make straight past that forklift till you hit the barracks. You’ll run right into the PX.’

It took both Mingolla and Baylor to drag Gilbey away from the Sikorsky, and he didn’t stop shouting until they drew near the forklift with its load of coffins: a giant’s treasure of enormous silver ingots. Then he grew silent and lowered his eyes. They wangled a ride with an MP corporal outside the PX, and as the jeep hummed across the concrete, Mingolla glanced over at the Sikorsky that had transported them. The two pilots had spread a canvas on the ground, had stripped to shorts, and were sunning themselves. But they had not removed their helmets. The weird juxtaposition of tanned bodies and black heads disturbed Mingolla, reminding him of an old movie in which a guy had gone through a matter transmitter along with a fly and had ended up with the fly’s head on his shoulders. Maybe, he thought, the pilots’ story about the helmets was true: they were impossible to remove. Maybe the war had gotten that strange.

The MP corporal noticed him watching the pilots and let out a

barking laugh. ‘Those guys,’ he said, with the flat emphatic tone of a man who knew whereof he spoke, ‘are fuckin’ nuts!’

Six years before, San Francisco de Juticlan had been a scatter of thatched huts and concrete-block structures deployed among palms and banana leaves on the east bank of the Río Dulce, at the junction of the river and a gravel road that connected with the Pan American Highway; but it had since grown to occupy substantial sections of both banks, increased by dozens of bars and brothels: stucco cubes painted all the colors of the rainbow, with a fantastic bestiary of neon signs mounted atop their tin roofs. Dragons; unicorns; fiery birds; centaurs. The MP corporal told Mingolla that the signs were not advertisements but coded symbols of pride; for example, from the representation of a winged red tiger crouched among green lilies and blue crosses, you could deduce that the owner was wealthy, a member of a Catholic secret society, and ambivalent toward government policies. Old signs were constantly being dismantled, and larger, more ornate ones erected in their stead as testament to improved profits, and this warfare of light and image was appropriate to the time and place because San Francisco de Juticlan was less a town than a symptom of war. Though by night the sky above it was radiant, at ground level it was mean and squalid. Pariah dogs foraged in piles of garbage, hardbitten whores spat from the windows, and, according to the corporal, it was not unusual to stumble across a corpse, likely a victim of the gangs of abandoned children who lived in the fringes of the jungle. Narrow streets of tawny dirt cut between the bars, carpeted with a litter of flattened cans and feces and broken glass; refugees begged at every corner, displaying burns and bullet wounds. Many of the buildings had been thrown up with such haste that their walls were tilted, their roofs canted, and this made the shadows they cast appear exaggerated in their jaggedness, like shadows in the work of a psychotic artist, giving visual expression to a pervasive undercurrent of tension. Yet as Mingolla moved along, he felt at ease, almost happy. His mood was due in part to his hunch that it was going to be one hell of an R and R (he had learned to trust his hunches); but it spoke mainly to the fact that towns like this had become for him a kind of afterlife, a reward for having endured a harsh term of existence.