Life in a Medieval City (18 page)

Read Life in a Medieval City Online

Authors: Frances Gies,Joseph Gies

Tags: #General, #Juvenile literature, #Castles, #Troyes (France), #Europe, #History, #France, #Troyes, #Courts and Courtiers, #Civilization, #Medieval, #Cities and Towns, #Travel

The bell founder signs his work with the mark of a shield with three bells, a pot and a mortar, and sometimes with an inscription such as “Iohannes Sleyt Me Fecit” or “Iohannes De Stafforde Fecit Me in Honore Beate Marie,” or a bit of bell ringer’s verse: “I to the church the living call, and to the grave do summon all,” or “Sometimes joy and sometimes sorrow, marriage today and death tomorrow.”

Dominating the scene is the great incomplete shell of the cathedral itself. The rising wall is covered with scaffolding fashioned of rough-hewn poles lashed together in trusses, with the diagonals cinched by tourniquets. Inside the walls a giant crane stands on a platform, its long arm reaching over the wall, dangling a line to the ground. When the line is secured around a building stone, word is passed from the ground outside via the men on the scaffold to the crane operator inside. The “engine” is started—a yoke of oxen harnessed to walk in a circle around the crane platform, winding the line on a windlass. The driver commands, the whip snaps, the oxen shove, the windlass turns, the line moves, the block rises, till it reaches the scaffold where the men are waiting. Cries go back and forth over the wall, the “engine” is halted, the men on the scaffold grasp the block, maneuver it in, call for another lift of a foot or so, then for a back-off to lower the stone in place, and amid shouts, commands and perhaps a few curses, the block is securely bedded in the prepared mortar course. Smaller stones are lifted by a lighter windlass, which is turned by a crank—another invention of the Middle Ages.

Most of the masonry work consists of old, long-practiced technique. The Romans maneuvered bigger blocks into position than any that medieval masons tackle. On the Pont du Gard there are stones eleven feet in length. But medieval masons are steadily improving their ability to handle large masses of stone. In the bases of piers, monoliths weighing as much as two tons are sometimes used. The Romans habitually built without mortar, dressing their stones accurately enough so that walls and arches stood simply by their own weight. Some builders are beginning to essay this, but by and large medieval masonry relies on mortar.

Thirteenth-century timbering is also less daring than Roman. The entrance to the choir at present is a veritable maze of heavy crisscrossing timbers supporting the work in progress on the first bay of the choir vault.

5

The rough-hewn timbers stand in a network of Xs and Vs, supporting a rude ogival arch of timber on which the stone ribs are laid. The timber arch does not meet the stone accurately at all points, and where it fails to do so, chips or blocks are driven into the interstice.

In the early Middle Ages, the problem of fireproofing a church was reduced to the question of how to support a masonry vault with something less expensive than a thick wall. Roman engineers actually had a solution, the groined vault, contrived by making two of their ordinary semicircular “barrel vaults” intersect. The weight of the resulting structure was distributed to the corners, permitting it to be supported by piers, and so providing architectural advantages. But the groined vault, though used by the Romans in the Baths of Caracalla and by some builders since, presents a difficulty. The variously-shaped stone blocks must be meticulously cut; in other words, they are expensive.

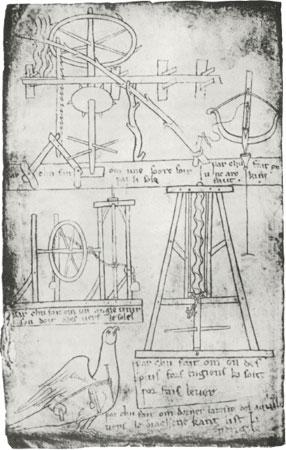

Medieval machinery

, sketched by Villard de Honnecourt: top, mechanical saw for splitting beams; upper right, crossbow with sighting device; middle, hoisting machines; lower left, a mechanical eagle.

When medieval engineers found another way to mount a vault on piers they opened the door to Gothic architecture.

6

The Romans, acquainted with the pointed arch, found as little use for it as had the Greeks or Persians. It was French engineers of the twelfth century who made the discovery that two pointed arches, intersecting overhead at right angles, created an exceptionally strong stone skeleton, which could rest solidly on four piers. The stones were easy to cut and the spaces between could be filled with no exceptional skill on the part of the mason. And once mounted on its piers, the new vault could be raised to astonishing heights at moderate cost. The higher the vault, the more room for windows, and the better illuminated the church. A problem remained. As the vault rose, the piers required reinforcement to contain the thrust from the ribs, which threatened to topple them outward.

At first this difficulty was met by buttressing, that is, by giving an extra thickness to the exterior wall at the point where the rib connected. But this made it impossible to put side aisles in the church. The spectacular answer to the problem was the flying buttress, a beam of masonry that arched airily over the low roof of the side aisle to meet the point where the rib supporting the main vault connected with the top of the pier.

By 1250 the intricate combination of piers, ribs, and flying buttresses has become an established, functioning system, one which would have opened the eyes of Roman engineers.

Medieval builders have a better theoretical grasp of structural relationships than had their Roman predecessors, who often used unnecessarily heavy underpinnings. But there is still no such thing as theoretical calculation of stress, or even accurate measurement. Gothic churches are full of small errors of alignment, and sometimes a vault crashes. But with or without a grounding in theory, the new technology usually works, and works so well that though originally conceived in a spirit of economy, it has had a history similar to that of many other engineering advances. It has opened such social and aesthetic possibilities that in the end it has raised the cost of church construction. A hundred years ago the nave of one of the first Gothic cathedrals, at Noyon, soared to a height of eighty-five feet. Notre-Dame-de-Paris then rose to a hundred and fifteen feet, Reims to a hundred and twenty-five, Amiens to a hundred and forty, and Beauvais, just started, is aiming at over a hundred and fifty. Spires above the bell towers reach much higher, that of Rouen ultimately holding the championship at four hundred and ninety-five feet, higher than the Great Pyramid.

It is no accident that the development of Gothic architecture coincides with growing affluence. The bishop of Troyes could not have undertaken the new Cathedral of St.-Pierre two hundred years ago, not merely for want of engineering technique but for want of cash.

Money to pay for a cathedral comes from a number of sources. Added to the steadily growing revenues of the chapter and its dependencies are the profits from indulgences, which are the bishop’s monopoly. Many an avaricious baron has made peace with God by a handsome gift to a cathedral building fund. Deathbed bequests

7

are an especially fruitful source. The Church has campaigned long and shrewdly in favor of wills. Relics, which are part of the reason for building a cathedral, help raise money long before its completion. They attract pilgrims to the site, and since they are portable, they can be sent on mission to the surrounding countryside. Those of Laon journeyed as far south as Tours and north and west to England, where they visited Canterbury, Winchester, Christchurch, Salisbury, Wilton, Exeter, Bristol, Barnstable, and Taunton, performing miracles all along the way.

Even with all the resources of guilty consciences and psychological cures few cathedrals would be completed without the assistance of an entirely different factor: civic pride. The cathedral belongs to the town as well as to the bishop and is often used for secular purposes, such as town meetings. The burghers can be counted on to give it financial support, not merely through private contributions by the wealthy, but through corporate contributions by the guilds. Proud, devout, and affluent, the guilds compete with each other and with the great lords and prelates in endowing the pictures in glass of Bible stories and lives of the saints which are the chief glory of the cathedral, and which represent no less than half its total cost. For at least one cathedral, Chartres, we have precise figures: of one hundred and two windows, forty-four were donated by princes and other secular lords, sixteen by bishops and other ecclesiastics, and forty-two by the town guilds, who signed their identities with panels representing their crafts.

Windows are not all installed at once. A cathedral’s glass may be incomplete a hundred or two hundred years after the masonry is begun. The installation of a window in the clerestory of the choir is an event. The mosaic of colored glass is passed up from hand to hand and eased onto the projecting dowels of a horizontal iron saddle bar, the ends of which are buried in the masonry. A second narrow bar with openings that match the dowels fits parallel to the first bar and is fastened to it with pins. Together these bars, and the vertical stanchions, hold the glass in place and brace it against wind pressure.

Glass is not manufactured at the site of the cathedral, nor indeed even inside the city. The glassmakers locate their hut in a nearby forest, which supplies fuel and raw materials. Glassmaking is a very ancient art, and “stained” (colored) glass is at least several centuries old, but not until recently has it been in great demand. The new technology and the new affluence have created this major industry.

The glassmaking process, brought to the West by the Venetians, has changed little through the ages—two parts ash (beechwood for best results) to one part sand in the mixture, a hot fire in a stone furnace, blowing and cutting. Blowing is done with a six-foot-long tube, creating a bubble of glass in the form of a long cylinder closed at one end and nearly closed at the other. The cylinder is cut along its length with a white-hot iron, reheated, and opened along the seam into a sheet. The result is a piece of glass of uneven thickness, full of irregularities—bubbles, waves, lines—not very clear, of a pale greenish color. Medieval glassmakers, like their predecessors, cannot turn out a good transparent, colorless pane. One consequence has been that glass never had much appeal as material for the small windows of the Romanesque buildings.

The vast Gothic window spaces have changed the situation. Imperfections in the glass are unimportant, as coloring becomes not only acceptable but desirable. Colors, apart from the indeterminate green of “natural” glass, have always been readily obtainable by adding something to the basic mixture—cobalt for blue, manganese for purple, copper for red. As the big new church windows came into fashion the glaziers took to cutting up sheets of colored glass and leading bits together to make a design. Almost at once the idea occurred of making the designs not merely geometric but pictorial, and the art of stained glass was born. Art begets artists, and the function of assembling the pieces of glass into pictures that the sun turned into miracles of radiant color devolved on those who were skilled at it.

The cathedral windows are made from glass manufactured in the hut in the forest, but are designed and assembled in a studio near the cathedral, under the direction of the master glazier. His craft demands special knowledge (often transmitted from father to son), exceptional skill, and long experience. Like the master builder and the masons, the window maker and the workmen he commands are itinerants, moving from town to town and church to church.

The master glazier oversees every part of the operations of his shop, but one function that he reserves for himself alone is that of drawing the picture. First he produces a small scale-drawing of the whole window on parchment, coloring in the segments. Then he draws a cartoon the size of the panel on which he is working, not on parchment, but on the wooden surface of an enormous bench or table of white ash. A panel is sketched on the table in the form of a diagram in black and white, indicating by numbers and letters which colors are to be used in each tiny section. As the big panes made by the glaziers are cut roughly to size with a hot iron under the master’s eye, each piece is laid in its correct position on the table. It does not quite fit. Using a notched tool called a grozing iron, a workman dextrously nibbles the piece’s edges to precision.

A visitor watching the workmen fashion the legend of St. Nicholas, or the story of the Wise and Foolish Virgins, for St.-Pierre’s windows would scarcely be able to make out any picture at all. The work table is a jigsaw confusion of oddly-shaped segments, with only here and there a recognizable fragment: a purple demon, or the white and yellow robes of the virgins.

Variations in the thickness of the glass produce colors that vary in intensity. In windows of the twelfth century this accident was used to artistic effect in the alternation of light and dark segments. But the men working on St.-Pierre’s glass do not take time to sort it out; the thirteenth century’s booming market has eliminated this subtlety of workmanship. Even so, the effects achieved are astounding, and will in centuries to come be attributed by legend to a secret process known only to medieval glaziers. In reality the master glazier has no secrets.

8

He carefully paints the lines in the drapery of the garments, the features of the faces, and decorative details; then he supervises the firing of the segments in the kiln and sees that they are assembled properly. The assembly is accomplished by means of doubly-grooved lead cames bent to follow the shape of the glass segments. The cames are soldered to each other at their intersections and sealed with putty, to keep out the rain. Lead is the source of another aesthetic accident: it keeps the colors from radiating into each other when the sunlight strikes.