Life in a Medieval Village (18 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Village Online

Authors: Frances Gies

Besides the grain crops, harvest included “pulling the peas,” the vegetable crops that matured in late September and whose harvest also required careful policing against theft.

Yields for the villagers could scarcely have exceeded those of the demesne, which enjoyed so many advantages. Three and a half to one was generally a very acceptable figure for wheat, with barley a bit higher and oats lower, and bad crops always threatening. R. H. Hilton has calculated that an average peasant on a manor of the bishop of Worcester might feed a family of three, pay a tithe to the church, and have enough grain left to sell for twelve or thirteen shillings, out of which his rent and other cash

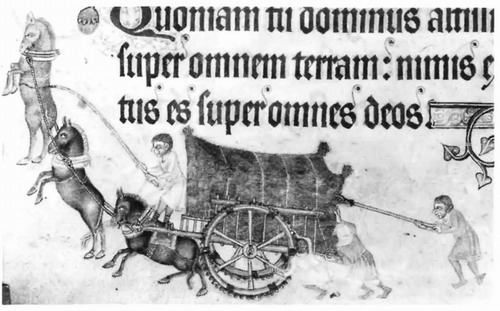

Carting. British Library, Luttrell Psalter, Ms. Add. 42130, f. 173v.

obligations would have to come.

47

If he was required to pay cash in place of his labor obligation, he would need to make up the difference by sale of poultry or wool, or through earnings of wife or sons. As Fernand Braudel observes, “The peasants were slaves to the crops as much as to the nobility.”

48

Harvest time was subject to more bylaws than all the rest of the year together. “The rolls of the manor courts are peppered with fines levied for sheaf stealing in the field, and a close watch had to be kept in the barn as well,” says Ault.

49

The small size of the medieval sheaf, twenty to a bushel, contributed to temptation,

Seneschaucie

mentioning as familiar places of secreting stolen grain “bosom, tunic, or boots, or pockets or sacklets hidden near the grange.”

50

Another communal agreement was needed for post-harvest grazing of the stubble. Sometimes a common date was set, such as Michaelmas, for having everybody’s harvest in. Bylaws might specify that a man could pasture his animals on his own land as soon as his neighbors’ lands were harvested to the depth of an acre. This was easy to do with cows, which could be restrained

within a limited space. Sheep and hogs, on the other hand, had to wait until the end of autumn.

51

The lord’s threshing and winnowing were followed by the villagers’, with whole families again joining in. Winter was the slack season, at least in a relative sense. Animals still had to be looked after, and harness, plows, and tools mended. Fences, hurdles, hedges, and ditches, both the lord’s and those of the villagers, had to be repaired to provide barriers wherever arable land abutted on a road or animal droveway. Houses, byres, pens, and sheds needed maintenance. So did equipment: “The good husbandman made some at least of his own tools and implements.”

52

The true odd-job men of the village were the cotters. They rarely took part in plowing, having neither plows nor plow beasts, but turned to “hand-work” with spade or fork, sheep-shearing, wattle-weaving, bean-planting, ditch-digging, thatching, brewing, even guarding prisoners held for trial. They were commonly hired by wealthier villagers at harvest time, getting paid with an

Threshing, using jointed flail. British Library, Luttrell Psalter, Ms. Add. 42130, f. 74v

.

eleventh, a fifteenth, or a twentieth sheaf. Cotters’ wives and daughters were in demand for weeding and other chores.

53

Yet though they occupied the lowest rung on the village ladder, even cotters were capable of asserting their rights, as a remarkable entry in the Elton court rolls of 1300 testifies. Among the few service obligations of the Elton cotters was that of assisting in the demesne haymaking. A score of cotters, including three women, were prosecuted

because they did not come to load the carts of the lord with hay to be carried from the meadow into the manor as formerly they were wont to do in past times, as is testified by Hugh the claviger. They come and allege that they ought not to perform such a custom save only out of love

(amor),

at the request of the serjeant or reeve. And they pray that this be inquired into by the free tenants and others. And the inquest [a special panel of the court] comes and says that the abovesaid cotters ought to make the lord’s hay into cocks in the meadows and similarly in the courtyard of the lord abbot, but they are not bound to load the carts in the meadows unless it be out of special love at the request of the lord.

That left the lord’s hay sitting in haycocks in his meadow and the cotters in the manor courtyard waiting for it to be brought to them. The steward confessed himself unable to resolve the dispute without reference to the rule and precedent given in the register at Ramsey, and so ordered “that the said cotters should have parley and treaty with the lord abbot upon the said demand.” The ultimate issue is not recorded.

54

The pathetic picture in

Piers Plowman

of the peasant husband and wife plowing together, his hand guiding the plow, hers goading the team, their baby and small children nearby, illustrates the fact that the wife of a poor peasant had to turn her hand to every kind of labor in sight.

55

For most of the time, however, in most peasant households, the tasks of men and

women were differentiated along the traditional lines of “outside” and “inside” work. The woman’s “inside” jobs were by no means always performed indoors. Besides spinning, weaving, sewing, cheese-making, cooking, and cleaning, women did foraging, gardening, weeding, haymaking, carrying, and animal-tending. They joined in the lord’s harvest boon unless excused, and helped bring in the family’s own harvest. Often women served as paid labor, receiving at least some of the time wages equal to men’s.

56

R. H. Hilton believes that peasant women in general enjoyed more freedom and “a better situation in their own class than was enjoyed by women of the aristocracy, or the bourgeoisie, a better situation perhaps than that of the women of early modern capitalist England.”

57

The statement does not mean that peasant women were better off than wealthier women, only that they were less constricted within the confines of their class. “The most important general feature of their existence to bear in mind,” Hilton adds, “[is] that they belonged to a working class and participated in manual agricultural labor.”

58

For many village women one of the most important parts of the daily labor was the care of livestock. Poultry was virtually the

Woman milking cow. Bodleian Library, Ms. Bodl. 764, f. 41v

.

Woman feeding chickens, holding a distaff under her arm. British Library, Luttrell Psalter, Ms. Add. 42130, f. 166v.

Woman on the left is spinning, using the thirteenth-century invention, the spinning wheel. Woman on the right is carding (combing) wool. British Library, Luttrell Psalter, Us. Add. 42130, f. 103.

woman’s domain, but feeding, milking, washing, and shearing the larger livestock often fell to her also.

The biggest problem with livestock was winter feed, the shortage of which was once thought to have provoked an annual “Michaelmas slaughter.” Given the high rate of loss to natural causes, an annual slaughter would have threatened the survival

of a small flock or herd.

59

The feed shortage certainly played a role in keeping numbers of animals down, but some successful peasants just as certainly overcame the problem. At Bowerchalk in Wiltshire, twenty-three tenants are known to have owned 885 sheep, or 41 per owner; at Merton, eighty-five tenants owned 2,563 sheep, and one is known to have owned 158.

60

Individual ownership within a combined flock was kept straight by branding or by marking with reddle (red ochre), many purchases of which are recorded.

61

Among peasants as among lords, sheep were esteemed as the “cash crop” animals. Though worth at best only one or two shillings, compared with two and a half shillings for a pig, they had unique fivefold value: fleece, meat, milk, manure, and skin (whose special character made it a writing material of incomparable durability). Lambing time was in early spring, between winter and spring sowing, so that the lambs, weaned at twelve weeks, could accompany their mothers to graze the harvest stubble of last year’s wheatfield.

62

The sheep were sheared in mid-June and the fleeces carted to market, probably, in the case of Elton, to Peterborough, about eight miles away. Medieval fleeces weighed from a pound to two and a half pounds, much below the modern average of four and a half pounds.

63

Pigs were the best candidates for a Michaelmas slaughter, since their principal value was as food and since their meat

Weeding, using long-handled tools. British Library, Luttrell Psalter, Ms. Add. 42130, f. 17s.