Life in a Medieval Village (16 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Village Online

Authors: Frances Gies

Wakes commonly turned into occasions of drinking and merriment, condemned by the Church. Robert Grosseteste warned that a dead man’s house should be one of “sorrow and remembrance,” and should not be made a house of “laughter and play,” and a fourteenth-century preacher complained that people “finally like madmen make…merry at our death, and take our burying for a bride ale.”

83

In the Ramsey Abbey village of Great Raveley in 1301, ten Wistow men were fined after coming “to watch the body of Simon of Sutbyr through the night,” because returning home they “threw stones at the neighbors’ doors and behaved themselves badly.”

84

Village funerals were usually starkly simple. The body, sewed in a shroud, was carried into the church on a bier, draped with a black pall. Mass was said, and occasionally a funeral sermon was delivered. One in John Myrc’s collection,

Festiall,

ends: “Good men, as ye all see, here is a mirror to us all: a corpse brought to the church. God have mercy on him, and bring him

Fanciful funeral: animals carrying a bier draped with a pall. Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, Psalter and Book of Hours, Ms. 102, f. 76v-77.

into his bliss that shall last for ever…Wherefore each man and woman that is wise, make him ready thereto; for we all shall die, and we know not how soon.”

85

A villager was buried in a plain wooden casket or none at all, in the churchyard, called the “cemetery,” from

coemeterium

(dormitory), the sleeping place of the Christian dead. Here men and women could slumber peacefully, their toil finished, until the day of resurrection.

THE VILLAGE AT WORK

F

OR THE MEDIEVAL VILLAGER, WORK WAS THE

ruling fact of life. By sunup animals were harnessed and plows hitched, forming a cavalcade that to the modern eye would appear to be leaving the village to work outside it. Medieval people felt otherwise. They were as much in their village tramping the furrowed strips as they were on the dusty streets and sunken lanes of the village center. If anything, the land which literally provided their daily bread was more truly the village. The geography was a sort of reverse analogue of the modern city with its downtown office towers where people work and its suburban bedroom communities where they eat and sleep.

Whether Elton had two or three fields in the late thirteenth century is unknown. Whatever the number, they were twice subdivided, first into furlongs (more or less rectangular plots “a furrow long”), then into selions, or strips, long and narrow sets of furrows. Depending on the terrain, a village’s strips might be several hundred yards long; the fewer turns with a large plow team the better. The strip as a unit of cultivation went far back, probably antedating the open field system itself. Representing the amount of land that could conveniently be plowed in a

Aerial view of the deserted village of Newbold Grounds (Northamptonshire), showing house plots, sunken paths and roads, and the ridge-and-furrow of the surrounding fields. British Crown Copyright/RAF Photograph.

day—roughly half a modern acre—it probably originated in the parcellation of land forced by a growing population. By the late thirteenth century the distribution of a village’s strips was haphazard, some villagers holding many, some few, and all scattered and intermingled. The one certainty was that everyone who held land held strips in both or all three fields, in order to guarantee a crop every year regardless of which field lay fallow.

The furlong, or bundle of strips, was the sowing unit, all the strips in a given furlong being planted to the same crop. Many furlongs appear by name in the Elton court records: “Henry in the Lane [is fined] for bad plowing in Hollewell furlong, sixpence,” indicating, incidentally, that the lord’s demesne land was scattered, like the peasants’.

1

Within each furlong the strips ran parallel, but the furlongs themselves, plotted to follow the ambient pattern of drainage, lay at odd angles to each other, with patches of rough scattered throughout. A double furrow or a balk of unplowed turf might separate strips, while between some furlongs headlands were left for turning the plow. Wedges of land (gores) created by the asymmetry of the furlongs and the

character of the terrain were sometimes cultivated by hoe.

2

The total appearance of an open field village, visible in aerial photographs of many surviving sites, is a striking combination of the geometric and the anarchic.

Beyond the crazy-quilt pattern of arable land stretched meadow, waste, and woodland, hundreds of acres that were also part of the village and were exploited for the villagers’ two fundamental purposes: to support themselves and to supply their lord. But the most significant component of the open field village was always its two or three great fields of cultivated land. The difference between a two- and a three-field system was slighter than might appear at first glance. Where three fields were used, one lay fallow all year, a second was planted in the fall to winter wheat or other grain, the third was planted in the spring to barley, oats, peas, beans, and other spring crops. The next year the plantings were rotated.

In the two-field system one field was left fallow and the other divided in two, one half devoted to autumn and the other to spring crops. In effect, the two-field system was a three-field system with more fallow, and offered no apparent disadvantage as long as enough total arable was available. If, however, a growing village population pressed on the food supply, or if market demand created an opportunity hard to resist, a two-field system could be converted to three-field. Many two-field systems were so converted in the twelfth and especially the thirteenth century, with a gain of one-third in arable.

3

Multifield systems, which could accommodate crop rotation, were also common, especially in the north of England. In some places, the ancient infield-outfield system survived, the small infield being worked steadily with the aid of fertilizer, and the large outfield treated as a land reserve, part of which could be cultivated for several successive years (making plowing easier) and then left fallow for several.

4

But in the English Midlands, and much of northwest Europe, the classic two- or three-field system of open field husbandry prevailed. It involved three essentials: unfenced arable divided into furlongs and strips; concerted agreement about crops and

cultivation; and common use of meadow, fallow, waste, and stubble.

Implied was a fourth essential: a set of rules governing details, and a means of enforcing them. Such rules were developed independently in thousands of villages in Britain and on the Continent, at first orally, but by the late thirteenth century in written form as village bylaws. The means of enforcement was provided by the manorial court. Surviving court records include many bylaw enactments and show the existence of many more by citation. For stewards, bailiffs, reeves, free tenants, and villeins, they spelled out a set of restrictions and constraints on plowing, planting, harvesting, gleaning, and carrying. They gave emphatic attention to theft and chicanery, from stealing a neighbor’s grain to “stealing his furrow” by edging one’s plow into his strip, “a major sin in rural society”

5

(Maurice Beresford). “Reginald Benyt appropriated to himself three furrows under Westereston to his one rod from all the strips abutting upon that rod and elsewhere at Arnewassebroc three furrows to his one headland from all the strips abutting upon that headland,” for which Reginald was fined 12 pence by the Elton manorial court of 1279.

6

Bylaws stipulated the time the harvested crop could be taken from the fields (in daylight hours only), who was allowed to carry it (strangers not welcome), and who was allowed to glean. All able-bodied adults were conscripted for reaping. “And [the jurors] say that Parnel was a gleaner in the autumn contrary to the statutes. Therefore she is in mercy [fined] sixpence.”

7

“The wife of Peter Wrau gleaned…contrary to the prohibition of autumn.”

8

Bylaws ruled the period when the harvest stubble should be opened to grazing, and for which kind of animals, when sheep were barred from the meadows, and when tenants must repair ditches and erect, remove, and mend fences. (Only the lord’s land could be permanently fenced, and only if it lay in a compact plot.) Repeatedly, through the year, the village animals were herded into or driven off the open fields as crop, stubble, and fallow succeeded each other.

The regulation of grazing rights was fundamental to the oper

ation of open field farming. The lord’s land was especially inviolate to beastly trespass: “Robert atte Cross for his draft-beasts doing damage in the lord’s furlong sown with barley, [fined] sixpence.”

9

On some manors grazing rights were related to the size of the holding. A Glastonbury survey of 1243 found the holder of a virgate endowed with pasture enough for four oxen, two cows, one horse, three pigs, and twelve sheep, calculated as the amount of stock required to keep a virgate of land fertile.

10

The open field system was thus not one of free enterprise. Its practitioners were strictly governed in their actions and made to conform to a rigid pattern agreed on by the community, acting collectively.

Neither was it socialism. The strips of plowed land were held individually, and unequally. A few villagers held many strips, most held a few, some held none. Animals, tools, and other movable property were likewise divided unequally. The poor cotters eked out a living by working for the lord and for their better-off neighbors who held more land than their families could cultivate, whereas these latter, by marketing their surplus produce, were able to turn a profit and perhaps use it to buy more land.

How much of his time a villager could devote to cultivating his own tenement depended partly on his status as free or unfree, partly on the size of his holding (the larger the villein holding, the larger the obligation), and partly on his geographical location. In England “the area of heavy villein labor dues—say two or more days each week—was relatively small,” consisting mostly of several counties and parts of counties in the east.

11

In the rest of the country, though rules varied from manor to manor, the level of villein obligations tended to be lower. In several counties in the north and northwest they were very light or nonexistent.

Huntingdonshire, containing Ramsey Abbey and Elton, was in the very heart of the heavy-labor region, where the obligation was basically two days’ work a week. In Elton, the dozen free tenants owed very modest, virtually token service. The cotters owed little service because they held little or no land. Only the

two score villein virgaters owed heavy week-work, amounting to 117 days a year (the nine half-virgaters owed fifty-eight and a half days).

12

In addition, the Elton virgater owed a special service, the cultivation of half an acre of demesne land summer and winter, including sowing it with his own wheat seed, reaping, binding, and carrying to the lord’s barn.

13

Some question exists about the length of the work day required of tenants. A Ramsey custumal for the manor of Abbot’s Ripton stipulates “the whole day” in summer “from Hokeday until after harvest,” and “the whole day in winter,” but during Lent only “until after none (mid-afternoon).”

14

In some places a work day lasted until none if no food was supplied, and if the lord wanted a longer day, he was obliged to provide dinner. Another determinant of the length of the working day may have been the endurance of the ox (less than that of the horse).

15

The annual schedule of week-work at Elton divided the year into three parts:

From September 29 (Michaelmas) of one year to August 1 (Gules of August) of the following year, two days’ work per week (for a virgater).

From August 1 to September 8 (the Nativity of the Blessed Mary), three days’ work per week, with a day and a half of work for the odd three days. This stretch of increased labor on the demesne was the “autumn works.”

From September 8 to September 29, five days’ work a week, known as the “after autumn works.”

16

Thus the autumn and post-autumn works for the Elton virgater totaled thirty-one and a half days, half of the two critical months of August and September, when he had to harvest, thresh, and winnow his own crop.

The principal form of week-work was plowing. Despite employment of eight full-time plowmen and drivers on the Elton demesne, the customary tenants, with their own plows and animals, were needed to complete the fall and spring plowing and the summer fallowing to keep the weeds down. Default of the

plowing obligation brought punishment in the manor court: “Geoffrey of Brington withheld from the lord the plow work of half an acre of land. [Fined] sixpence.”

17

“John Page withholds a plowing work of the lord between Easter and Whitsuntide for seven days, to wit each Friday half an acre. Mercy [fine] pardoned because afterwards he paid the plowing work.”

18

By the same token, the main kind of work the villein did on his own land was plowing. Stage by stage through the agricultural year he worked alternately for the lord and for himself.

His plow (not every villein owned one) was iron-shared, equipped with coulter and mouldboard, and probably wheeled, an improvement that allowed the plowman to control the depth of furrow by adjusting the wheels, saving much labor. He might own an all-wooden harrow, made by himself from unfinished tree branches, or possibly a better one fashioned by the carpenter. Only the demesne was likely to own a harrow with iron teeth, jointly fabricated by the smith and the carpenter. The villein’s collection of tools might include a spade, a hoe, a fork, a sickle, a scythe, a flail, a knife, and a whetstone. Most virgaters probably owned a few other implements, drawn from a secondary array scattered through the village’s toolsheds: mallets, weeding hooks, sieves, querns, mortars and pestles, billhooks, buckets, augers, saws, hammers, chisels, ladders, and wheelbarrows. A number of villagers had two-wheeled carts. Those who owned sheep had broad, flat shears, which were also used for cutting cloth.

19

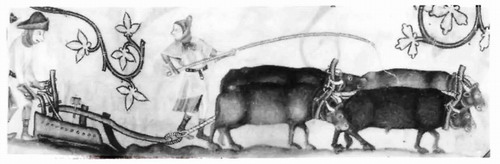

Heavy plow, with coulter and mouldboard, drawn by four oxen. British Library, Luttrell Psalter, Ms. Add. 42130, f. 170.