Life in a Medieval Village (11 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Village Online

Authors: Frances Gies

THE VILLAGERS:

HOW THEY LIVED

A

LL THE VILLAGERS OF ELTON, FREE, VILLEIN, AND

of indeterminate status, virgaters, half-virgaters, cotters, servants, and craftsmen, lived in houses that shared the common characteristic of impermanence. Poorly built, of fragile materials, they had to be completely renewed nearly every generation. At Wharram Percy, nine successive transformations of one house can be traced over a span of little more than three centuries. The heir’s succession to a holding probably often supplied an occasion for rebuilding. For reasons not very clear, the new house was often erected adjacent to the old site, with the alignment changed and new foundations planted either in postholes or in continuous foundation trenches.

1

Renewal was not always left to the tenant’s discretion. The peasant taking over a holding might be bound by a contract to build a new house, of a certain size, to be completed within a certain time span. Sometimes the lord agreed to supply timber or other assistance.

2

The lord’s interest in the proper maintenance of the houses and outbuildings of his village was sustained

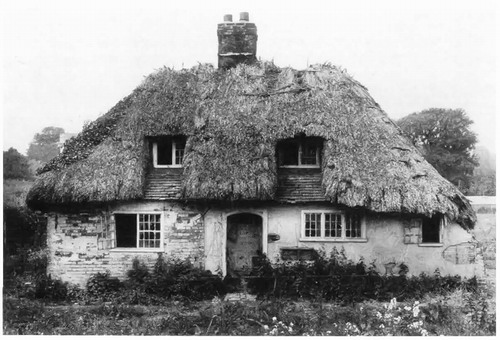

Fourteenth-century peasant house, St. Mary’s Grove cottage, Tilmanstone, Kent. Originally of one story, the house has retained the studs of the medieval partition that divided it into two rooms, and the framing of the window wall. Upper story and chimney were added in the seventeenth century, and the walls have been largely rebuilt. Royal Commission on the Historic Monuments of England.

by the manorial court. In Elton in 1306, Aldusa Chapleyn had to find pledges to guarantee that she would “before the next court repair her dwelling house in as good a condition as she received it.”

3

Two years later, William Rouvehed was similarly enjoined to “repair and rebuild his dwelling house in as good a condition as that in which he received it for a gersum [entry fee],”

4

and in 1331 three villagers were fined 12 pence each because they did not “maintain [their] buildings.”

5

All the village houses belonged to the basic type of medieval building, the “hall,” as did the manor house, the barns, and even the church: a single high-ceilinged room, varying in size depending on the number of bays or framed sections. In peasants’ houses, bays were usually about fifteen feet square.

6

The house of a rich villager such as John of Elton might

Outline of foundation of house at Wharram Percy, with entry in middle of long side.

consist of four or even five bays, with entry in the middle of a long side. Small service rooms were probably partitioned off at one end: a buttery, where drink was kept, and a pantry, for bread, dishes, and utensils, with a passage between leading to a kitchen outside. A “solar,” a second story either above the service rooms or at the other end, may have housed a sleeping chamber. A large hall might retain the ancient central hearth, or be heated by a fireplace with a chimney fitted into the wall. Early halls were aisled like churches, with the floor space obstructed by two rows of posts supporting the roof. Cruck construction had partially solved the problem, and by the end of the thirteenth century, carpenters had rediscovered the roof truss, known to the Greeks and Romans. Based on the inherent strength of the triangle, which resists distortion, the truss can support substantial weight.

7

A middle-level peasant, a virgater such as Alexander atte Cross, probably lived in a three-bay house, the commonest type. A cotter like Richard Trune might have a small one- or two-bay house. Dwellings commonly still lodged animals as well as human beings, but the byre was more often partitioned off and

sometimes positioned at right angles to the living quarters, a configuration that pointed to the European farm complex of the future, with house and outbuildings ringing a central court.

8

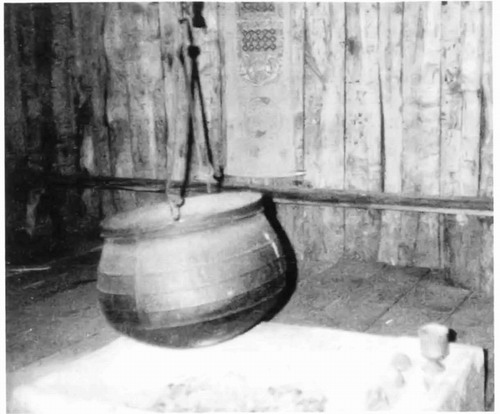

Interiors were lighted by a few windows, shuttered but unglazed, and by doors, often open during the daytime, through which children and animals wandered freely. Floors were of beaten earth covered with straw or rushes. In the center, a fire of wood, or of peat, commonly used in Elton,

9

burned on a raised stone hearth, vented through a hole in the roof. Some hearths were crowned by hoods or funnels to channel the smoke to the makeshift chimney, which might be capped by a barrel with its ends knocked out. The atmosphere of the house was perpetually smoky from the fire burning all day as water, milk, or porridge simmered in pots on a trivet or in footed brass or iron kettles. At night a fire-cover, a large round ceramic lid with holes, could be put over the blaze.

10

A thirteenth-century writer, contrasting the joys of a nun’s life with the trials of marriage, pictured the domestic crisis of a

Woman stirs footed pot on central hearth while holding baby. Trinity College, Cambridge, Ms. B 11.22, f. 25v.

Central hearth of house in reconstruction of Anglo-Saxon settlement at West ow.

wife who hears her child scream and hastens into the house to find “the cat at the bacon and the dog at the hide. Her cake is burning on the [hearth] stone, and her calf is licking up the milk. The pot is boiling over into the fire, and the churl her husband is scolding.”

11

Medieval sermons, too, yield a glimpse of peasant interiors: the hall “black with smoke,” the cat sitting by the fire and often singeing her fur, the floor strewn with green rushes and sweet flowers at Easter, or straw in winter. They picture the housewife at her cleaning: “She takes a broom and drives all the dirt of the house together; and, lest the dust rise…she casts it with great violence out of the door.” But the work is never done: “For, on Saturday afternoon, the servants shall sweep the house and cast all the dung and the filth behind the door in a heap.

But what then? Come the capons and the hens and scrape it around and make it as ill as it was before.” We see the woman doing laundry, soaking the clothes in lye (homemade with ashes and water), beating and scrubbing them, and hanging them up to dry. The dog, driven out of the kitchen with a basinful of hot water, fights over a bone, lies stretched in the sun with flies settling on him, or eagerly watches people eating until they throw him a morsel, “whereupon he turns his back.”

12

The family ate seated on benches or stools at a trestle table, disassembled at night. Chairs were rarities. A cupboard or hutch held wooden and earthenware bowls, jugs, and wooden spoons. Hams, bags, and baskets hung from the rafters, away from rats and mice. Clothing, bedding, towels, and table linen were stored in chests. A well-to-do peasant might own silver spoons, brass pots, and pewter dishes.

13

When they bathed, which was not often, medieval villagers used a barrel with the top removed. To lighten the task of carrying and heating water, a family probably bathed serially in the same water.

14

At night, the family slept on straw pallets, either on the floor of the hall or in a loft at one end, gained by a ladder. Husband and wife shared a bed, sometimes with the baby, who alternatively might sleep in a cradle by the fire.

Manorial accounts yield ample information about what the abbot of Ramsey ate, especially his feast-day diet, which included larks, ducks, salmon, kid, chickens at Easter, a boar at Christmas, and capons and geese on other occasions.

15

The monks ate less luxuriously. For their table, Elton (and other manors) supplied the cellarer at Ramsey with bacon, beef, lambs, herring, butter, cheese, beans, geese, hens, and eggs, as well as flour and meal. The inhabitants of the curia, including the reeve, the beadle, some of the servants, and “divers workmen and visitors from time to time,” also ate comparatively well, consuming large quantities of grain in various forms as well as peas, beans, bacon, chickens, ducks, cheese, and butter. Food was no small part of

the remuneration of servants and staff of a manor. Georges Duby cites the carters of Battle Abbey, who demanded rye bread, ale, and cheese in the morning, and meat or fish at midday.’

16

Less evidence exists for the diet of the average peasant. The thirteenth-century villager was a cultivator rather than a herdsman because his basic need was subsistence, which meant food and drink produced from grain. His aim was not exactly selfsufficiency, but self-supply of the main necessities of life.

17

These were bread, pottage or porridge, and ale. Because his wheat went almost exclusively to the market, his food and drink crops were barley and oats. Most peasant bread was made from “maslin,”

Netting small birds. British Library, Luttrell Psalter, Ms. Add. 42130, f. 63.

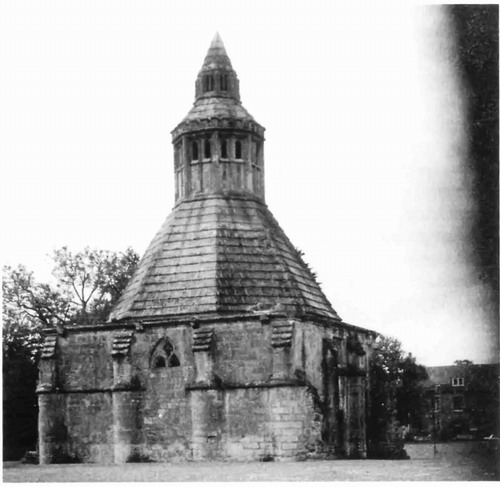

The abbot’s kitchen at Glastonbury Abbey contained four fireplaces for cooking.