Life in a Medieval Village (12 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Village Online

Authors: Frances Gies

a mixture of wheat and rye or barley and rye, baked into a coarse dark loaf weighing four pounds or more, and consumed in great quantities by men, women, and children.

18

For the poorer peasant families, such as the Trunes or the Saladins of Elton, pottage was favored over bread as more economical, since it required no milling and therefore escaped both the miller’s exaction and the natural loss of quantity in the process. Barley grains destined for pottage were allowed to sprout in a damp, warm place, then were boiled in the pot. Water could be drawn off, sweetened with honey, and drunk as barley water, or allowed to ferment into beer. Peas and beans supplied scarce protein and amino acids to both pottage and

bread. A little fat bacon or salt pork might be added to the pottage along with onion and garlic from the garden. In spring and summer a variety of vegetables was available: cabbage, lettuce, leeks, spinach, and parsley. Some crofts grew fruit trees, supplying apples, pears, or cherries. Nuts, berries, and roots were gathered in the woods. Fruit was usually cooked; raw fruit was thought unhealthy. Except for poisonous or very bitter plants, “anything that grew went into the pot, even primrose and strawberry leaves.”

19

The pinch came in the winter and early spring, when the grain supply ran low and wild supplements were not available.

Stronger or weaker, more flavorful or blander, the pottage kettle supplied many village families with their chief sustenance. If possible, every meal including breakfast was washed down with weak ale, home-brewed or purchased from a neighbor, but water often had to serve. The most serious shortage was protein. Some supplement for the incomplete protein of beans and peas was available from eggs, little from meat or cheese, though the wealthier villagers fared better than the poor or middling. E. A.

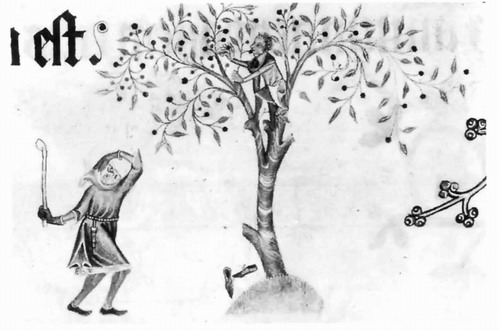

Gathering fruit. British Library, Luttrell Psalter, Ms. Add. 42130, f. 196v.

Kosminsky believed that the virgater and half-virgater could have “made ends meet without great difficulty, had it not been for the weight of feudal exploitation”—that is, the labor services and other villein obligations—but that a quarter virgate (five to eight acres) did not suffice even in the absence of servile dues.

20

H. S. Bennett calculated the subsistence level as lying between five and ten acres, “probably nearer ten than five.” The most recent scholarly estimate, by H. E. Hallam (1988), is that twelve acres was needed for a statistical family of 4.75. J. Z. Titow pointed out that more acreage was needed per family in a two-field system than a three-field system, since more of each holding was lying fallow. Cicely Howell, studying data from the Midland village of Kibworth Harcourt, concluded that not until the mid-sixteenth century could the half-virgater provide his family with more than eight bushels of grain a year per person from his own land. Poor families survived only by their varied activities as day laborers.

21

Besides the shortage of protein, medieval diets were often lacking in lipids, calcium, and vitamins A, C, and D.

22

They were also often low in calories, making the inclusion of ale a benefit on grounds of health as well as recreation. Two positive aspects of the villagers’ austere regimen—its low protein and low fat content—gave it some of the virtues of the modern “heartsmart” diet, and its high fiber was a cancer preventative.

A middling family like that of Alexander atte Cross or Henry Abovebrook probably owned a cow or two or a few ewes, to provide an intermittent supply of milk, cheese, and butter. Most households kept chickens and pigs to furnish eggs and occasional meat, but animals, like wheat, were often needed for cash sales to pay the rent or other charges. Salted and dried fish were available for a price, as were eels, which also might be fished from the Nene or poached from the millpond.

Medieval literature voiced the popular hunger for protein and fat. A twelfth-century Irish poet describes a dream in which a coracle “built of lard/ Swam a sweet milk sea,” and out of a lake rose a castle reached by a bridge of butter and surrounded by a palisade of bacon, with doorposts of whey curds, columns of

Men fishing with nets. British Library, Queen Mary’s Psalter, Ms. Royal 2B VII, f. 73

.

aged cheese, and pillars of pork. Across a moat of spicy broth covered with fat, guards welcomed the dreamer to the castle with coils of fat sausages.

23

It was a hungry world, made hungrier by intermittent crop failures, one series of which in the early fourteenth century brought widespread famine in England and northwest Europe. The later, even more devastating cataclysm of the Black Death so reduced the European population that food became comparatively plentiful and the peasants took to eating wheat. The poet John Gower (d. 1408) looked back on the earlier, hungrier period not in sorrow but rather with an indignant nostalgia that reflected the attitude of the elite toward the lower classes:

Laborers of olden times were not wont to eat wheaten bread; their bread was of common grain or of beans, and their drink was of the spring. Then cheese and milk were a feast to them; rarely had they any other feast than this. Their garment was of sober gray; then was the world of such folk well ordered in its estate.

24

The peasant’s “garment” has often been pictured in the illuminations of manuscripts, but only occasionally in “sober gray”; the colors shown are more often bright blues, reds, and greens. Whether Gower’s memory was accurate is uncertain. Peasants did have access to dyestuffs, and Elton had a dyer.

Over the period of the high Middle Ages, styles of clothing of nobles and townspeople changed from long, loose garments for both men and women to short, tight, full-skirted jackets and close-fitting hose for men and trailing gowns with voluminous sleeves, elaborate headdresses, and pointed shoes for women. Peasant dress, however, progressed little. For the men, it consisted of a short tunic, belted at the waist, and either short stockings that ended just below the knee or long hose fastened at the waist to a cloth belt. A hood or cloth cap, thick gloves or mittens, and leather shoes with heavy wooden soles completed the costume. The women wore long loose gowns belted at the waist, sometimes sleeveless tunics with a sleeved undergarment, their heads and necks covered by wimples. Underclothing, when it was worn, was usually of linen, outer garments were woolen.

The tunic of a prosperous peasant might be trimmed with fur, like the green one edged with squirrel found by three Elton boys in 1279 and turned over to the reeve.

25

A poor peasant’s garb, on the other hand, might resemble that of the poor man in Langland’s fourteenth-century allegory,

Piers Plowman,

whose “coat was of a [coarse] cloth called cary,” whose hair stuck through the holes in his hood and whose toes stuck through those in his heavy shoes, whose hose hung loose, whose rough mittens had worn-out fingers covered with mud, and who was himself “all smeared with mud as he followed the plow,” while beside him walked his wife carrying the goad, in a tunic tucked up to her knees, wrapped in a winnowing sheet to keep out the cold, her bare feet bleeding from the icy furrows.

26

The village world was a world of work, but villagers nevertheless found time for play. Every season was brightened by holiday intervals that punctuated the Christian calendar. Many of these were ancient pagan celebrations, appropriated by the Church, often with little alteration of their character. Each of the seasons of the long working year, from harvest to harvest, offered at least one holiday when work was suspended, games were played, and meat, cakes, and ale were served.

On November 1, bonfires marked All Hallows, an old pagan rite at which the spirits of the dead were propitiated, now renamed All Saints. Martinmas (St. Martin’s Day, November 11) was the feast of the plowman, in some places celebrated with seed cake, pasties, and a frumenty of boiled wheat grains with milk, currants, raisins, and spices.

The fortnight from Christmas Eve to Twelfth Day (Epiphany, January 6) was the longest holiday of the year, when, as in a description of twelfth-century London, “every man’s house, as also their parish churches, was decked with holly, ivy, bay, and whatsoever the season of the year afforded to be green.”

27

Villagers owed extra rents, in the form of bread, eggs, and hens for the lord’s table, but were excused from work obligations for the fortnight and on some manors were treated to a Christmas dinner in the hall.

This Christmas bonus often reflected status. A manor of Wells Cathedral had the tradition of extending invitations to two peasants, one a large landholder, the other a small one. The first was treated to dinner for himself and two friends and served “as much beer as they will drink in the day,” beef and bacon with mustard, a chicken stew, and a cheese, and provided with two candles to burn one after the other “while they sit and drink.” The poorer peasant had to bring his own cloth, cup, and trencher, but could take away “all that is left on his cloth, and he shall have for himself and his neighbors one wastel [loaf] cut in three for the ancient Christmas game to be played with the said wastel.”

28

The game was evidently a version of “king of the bean,” in which a bean was hidden in a cake or loaf, and the person who found it became king of the feast. On some Glastonbury Abbey manors, tenants brought firewood and their own dishes, mugs, and napkins; received bread, soup, beer, and two kinds of meat; and could sit drinking in the manor house after dinner.

29

In Elton the manorial servants had special rations, which in 1311 amounted to four geese and three hens.

30

In some villages, the first Monday after Epiphany was celebrated by the women as Rock (distaff) Monday and by the men as Plow Monday, sometimes featuring a plow race. In 1291 in

the Nottinghamshire village of Carlton, a jury testified that it was an ancient custom for the lord and the rector and every free man of the village to report with his plow to a certain field that was common to “the whole community of the said village” after sunrise on “the morrow of Epiphany” and “as many ridges as he can cut with one furrow in each ridge, so many may he sow in the year, if he pleases, without asking for license.”

31

Candlemas (February 2), commemorating Mary’s “churching,” the ceremony of purification after childbirth, was celebrated with a procession carrying candles. It was followed by Shrove Tuesday, the last day before Lent, an occasion for games and sports.

At Easter, the villagers gave the lord eggs, and he gave the manorial servants and sometimes some of the tenants dinner. Like Christmas, Easter provided villeins a respite—one week—from work on the demesne. Celebrated with games, Easter week ended with Hocktide, marked in a later day, and perhaps in the thirteenth century, by the young women of the village holding the young men prisoner until they paid a fine, and the men retaliating on the second day.

32

On May Day the young people “brought in the May,” scouring the woods for boughs from flowering trees to decorate their houses. Sometimes they spent the night in the woods.

Summertime Rogation Days, when the peasants walked the boundaries of the village, were followed by Whitsunday (Pentecost), bringing another week’s vacation for most villeins. St. John’s Day (June 24) saw bonfires lit on the hilltops and boys flourishing brands to drive away dragons. A fiery wheel was rolled downhill, symbolizing the sun’s attaining the solstice.

33

Lammas (August 1) marked the end of the hay harvest and the beginning of grain harvest, with its “boons” or precarias, when all the villagers came to reap the lord’s grain and were treated to a feast that in Elton in 1286 included an ox and a bullock, a calf, eighteen doves, seven cheeses, and a quantity of grain made into bread and pottage.

34

On one Oxfordshire manor it was customary for the villagers to gather at the hall for a songfest—“to sing harvest home.”

35

Elton records mention an

occasional “repegos,” a celebration at which the harvesters feasted on roast goose.

36