Lion of Jordan (21 page)

Authors: Avi Shlaim

The Israelis hoped that Jordan would refrain from joining either Iraq or the Egyptian-led bloc. The British consul-general in Jerusalem emphasized to an Israeli official that the Iraqi Army posed no threat to

Israel and that it would enter Jordan only to prevent the disintegration of the country.

28

From their other sources too the Israelis concluded that Iraq's main objective in sending troops would be to prevent Egypt from gaining control over Jordan, and at a later stage to make Jordan join the Baghdad Pact. What was not clear to the Israelis was for how long Jordan would be able to survive as an independent country between the two rival blocs. By preserving its freedom to react to Iraqi troop deployments in Jordan, Israel intended to signal to Hussein that he was running the risk of the destruction of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

29

It was a warning that Hussein could not afford to ignore. The best option left to him was to turn to Egypt, Syria and Saudi Arabia for economic and military assistance to help Jordan cope with the threat from Israel. Accordingly, he initiated intensive contacts with these neighbouring Arab countries, and these led to closer coordination and unity. Small quantities of arms were obtained, as well as a financial contribution towards the maintenance of the National Guard.

The border war with Israel thus had a two-fold effect. First, it accelerated the trend in Jordan's foreign policy away from the reliance on Britain and Iraq and towards Egypt and Syria. Second, the border war radicalized further the opposition groups inside Jordan and prompted them to adopt an even more militant anti-Israeli and anti-imperialist stand in the lead-up to the general elections. Many of their candidates resorted to slogans about recovering âthe usurped part of the homeland'.

30

The growing popular hostility towards Israel and the open calls by some of his Palestinian subjects for war on Israel, together with Israel's devastating military attacks, created serious internal problems for his regime. One was that the inhabitants of the border areas began to migrate to the cities to escape Israel's wrath. At a loss to know what to do, Hussein summoned Samir Rifa'i to seek his advice. Rifa'i recommended removing the National Guard from the border areas and replacing it with the army. He also suggested direct talks with the Israelis with the aim of reaching an informal agreement in the first instance. Rifa'i himself had had extensive first-hand experience of such talks as an aide to King Abdullah. He now suggested making contact with suitable Israelis whom he had met in the past. According to Israel's Jordanian informer, Hussein agreed and said he was prepared to accompany Rifa'i

to a secret meeting with Israeli representatives in Europe or America or Iraq.

31

There was no immediate follow-up to the suggestion of a face-to-face meeting with Israel, but Rifa'i planted the seed of what became one of the dominant ideas of Hussein's reign: dialogue across the battle lines. Already at this early stage it is possible to detect the beginning of an understanding on Hussein's part that Israel could be either his ultimate threat or his ultimate ally. The legacy of his grandfather pointed in the direction of a tacit alliance. King Abdullah had a closer understanding, based on a perception of common interests, and a more intimate political relationship with Israel than he did with any of his fellow Arab rulers. It was too soon for King Hussein at this stage in his career to follow in his grandfather's footsteps, but he was already reflecting on the advantages of contact and compromise with his belligerent Western neighbour.

In another private conversation earlier that year with Sir Alec Kirkbride, Hussein revealed a surprisingly moderate attitude towards Israel. He said he understood Israel's difficulty in taking back Palestinian refugees but thought that it ought to pay compensation to those who had left property behind â roughly 30 per cent of the total. Hussein estimated that, if given a choice between compensation and repatriation, no more than 10 per cent would opt for repatriation, and the majority of those would probably not stay there for more than six months. Hussein talked only about the refugee problem; he did not even mention the other key issue in the ArabâIsraeli dispute â borders. But Kirkbride had the impression that Hussein, and those among his advisers who wanted Jordan to survive as an independent country, realized that this depended to a large extent on a settlement with Israel.

32

Hussein's emergence as an Arab nationalist was thus combined with traditional Hashemite moderation and pragmatism on the subject of the Jewish state.

The Liberal Experiment

The dismissal of Glubb was only the first of two exceptionally important decisions made by Hussein in 1956: the second was to hold free elections in the autumn. On the wisdom of holding the promised elections, Hussein's advisers were divided. The old guard warned that elections could risk the rise to power of the leftist, pro-Nasser parties, who would create instability and proceed to challenge the monarchy. In his memoirs Hussein explained the thinking that led him to disregard this warning and to come down on the side of reform and change:

I take full responsibility for that period of experiment. I had felt deeply that for too long Jordanian political leaders had relied on outside help, and it was only natural that these politicians should meet with bitter opposition from the younger, rising men of ambition, who, like myself, thought it was time to throw off external shackles.

I had decided, therefore, that younger and promising politicians and Army officers should have a chance to show their mettle. I realized that many were very leftist, but I felt that even so most of them must genuinely believe in the future of their country, and I wanted to see how they would react to responsibility.

1

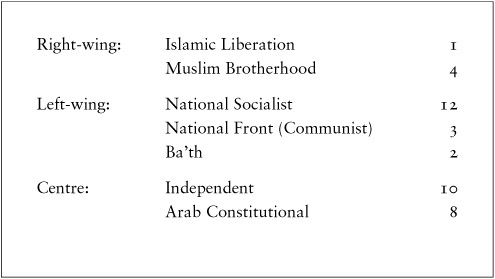

Jordan went to the polls on 21 October for the first truly free election in the history of the country. This was also the first election that was based more on political parties than on individuals. It did not follow, however, that the political parties had clear ideological positions or that the political process was essentially an inter-party contest. Everything in Jordanian politics revolved round money and patronage. The parties provided flexible frameworks to facilitate cooperation between individuals, especially at election time. There were also debates and divisions inside parties, especially on the left. Changing party for personal advantage was a common occurrence. The results were as follows:

These results represent a remarkable victory for the left-wing opposition parties, who wanted to abrogate Jordan's treaty with Britain and to substitute for it military pacts with Egypt and Syria. The largest of these parties was the National Socialist Party (NSP). It captured 12 out of the 40 seats of the lower house, even though its leader, Suleiman Nabulsi, narrowly failed in his bid for a seat. Nabulsi (1910â76) was born in Salt and educated at the American University of Beirut, which, despite its name, was the intellectual stronghold of pan-Arabism. He went into politics at a relatively young age and gained a reputation as an outspoken critic of the monarchy and a fiery Arab nationalist. The party that he formed in 1954 aimed to liberate politics from the control of the palace, and to work for greater equality at home and Arab unity abroad. Nabulsi was an admirer of Nasser and the leader of the opposition to the king's bid to take Jordan into the Baghdad Pact. He was not a communist, but he wanted to distance Jordan from the conservative Arab states.

The question in everybody's mind was: how would the king react to the verdict of the electorate? After some serious reflection, the king decided to be relaxed and accept the situation. At that time he had to contend with external pressures: he was courting the radical Arab states, and he was seeking the support of his Palestinian subjects. Precisely because of his radical Arab pedigee, Nabulsi could be instrumental in achieving these ends. The king therefore invited him, as the leader of the largest party, to form a government. (Jordan's constitution did not require ministers to be members of parliament.) âNabulsi was a leftist,' Hussein noted, âbut even so I felt he had to have his chance.'

2

Hussein

did this in the face of strong opposition from Zain. One contemporary observer saw Hussein's decision to bring Nabulsi and the National Socialists to power as the beginning of his rebellion against his mother: âShe was a traditionalist and the king was toying with adventurous, liberal and nationalist ideas and people. Queen Zain had been ruling the country, telling Hussein whom to appoint to this and that post. She began to lose her power when Hussein started making his own decisions.'

3

Whereas the decision to dismiss Glubb had been taken behind Zain's back, the appointment of Nabulsi was made in open defiance of her. It marked a further step in Hussein's political coming of age.

Even before Nabulsi assumed office, Hussein made another dramatic move to establish his credentials as an Arab nationalist. On 24 October he signed an agreement in Amman with Egypt and Syria, providing for a joint command of the armed forces of the three countries under the Egyptian commander-in-chief Major General Abdel Hakim Amer. Amer and General Tawfiq Nizamuddin, the Syrian chief of staff, were guests of honour at the opening of the new parliament by the monarch the following day. Two days later Nabulsi was appointed prime minister, and he also assumed the foreign affairs portfolio. Hussein gave Nabulsi a free hand to form his own cabinet. The result was a coalition that included three independents, one communist and one member of the extremely pro-Syrian Ba'th Arab Socialist Party. Abdullah Rimawi, the leader of the Ba'th, was given the relatively humble post of minister of state for foreign affairs. But he was the most outspoken anti-royalist in the government and exercised disproportionate influence through his alliance with Nabulsi's more extreme ministers and with some of the Free Officers in the army. He openly proclaimed his opposition to Jordanian independence and called for its merger with Syria. He was reputed to make frequent trips to Damascus and to return with suitcases full of money.

4

Not a single Hashemite loyalist was included in the cabinet.

Failure to win a majority in the Chamber of Deputies weakened the position of the new prime minister and made it more difficult for him to impose his authority on his argumentative colleagues. Nevertheless, during his short period in power, Nabulsi acted as a relatively free agent. He interpreted the 1952 constitution literally and held himself responsible to parliament, not to the palace. His government, for the

first time in Jordan's history, considered itself, rather than the king, as the principal decision-maker. The programme of the government reflected faithfully the electoral platforms of its constituent parts. The two main planks were to distance Jordan from Britain and to move closer to the radical Arab states. Hussein initially went along with this programme. The Amman pact for a unified military command fitted perfectly into this programme.

What the Jordanians did not know was that their conclusion of the new defence pact with Egypt coincided with a conspiracy between Britain, France and Israel to attack Egypt. Thus, on the eve of the Suez War, Jordan was in the curious position of having defence pacts with one of the villains as well as with the victim of what in Arab political discourse was usually referred to as

al-adwan al-thulathi

, or âthe tripartite aggression'. The timing of the Amman pact was singularly propitious for Israel. Israel's powerful propaganda machine was able to portray the military pact between its Arab neighbours to the north, east and south as a ring of steel justifying a pre-emptive attack. In reality, the Arab alliance was little more than a paper pact with no mechanism for creating an integrated command structure. In addition, Israel was trying to divert attention from its preparations to attack Egypt by deliberately raising the level of tension on the Jordanian front. The Amman pact contributed to the success of this strategic deception plan by focusing international attention on the JordanianâIsraeli conflict. More importantly, and to the evident satisfaction of the Israeli chief of staff, up to the last minute the general staffs of the Arab armies believed that Israel's intention was to march on Jordan.

5

It was Anthony Eden, however, who got Britain into this hopeless tangle. The road to Suez began when the neurotic prime minister declared a personal war on Nasser following the dismissal of Glubb. Relations between Egypt and the West deteriorated further when America withdrew its offer to finance the building of the Aswan Dam. Nasser retaliated on 26 July 1956, the fourth anniversary of the Free Officers' Revolution, by announcing the nationalization of the Suez Canal â a potent symbol of Western colonial domination. Though not illegal, this action convinced Eden that force would have to be used to remove Nasser from power. Eden was adamant that Nasser must not be permitted to have âhis thumb on our windpipe'. Because Dwight D. Eisenhower was equally convinced that force must not be used, Eden

resorted to the famous collusion with the Israelis and the French that paved the way to the tripartite attack on Egypt in October 1956. Israel got on the bandwagon of this colonial-style war at a later stage. The French were the match-makers between Britain and Israel. Like Eden, they saw the canal crisis as a replay of the 1930s, and, like him, they were determined that this time there must be no appeasement. They had another cause for complaint against âHitler on the Nile', as they called President Nasser â his support for the Algerian rebels against the French Army. France's generals at that time had only three priorities â Algeria, Algeria and Algeria. They calculated that if Nasser could be put in his place, the Algerian rebellion would collapse. Although each country had its own motives, the aim that united them was to knock Nasser off his perch.