Lion of Liberty (18 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

On March 17, 1776, British troops began evacuating Boston, and Virginia's Convention prepared to declare independence from England, naming Henry to a committee to create a new government. What was Virginia to become? The short struggle against Britain had made it clear that most colonies would be unable to stand alone as independent countries and survive. But Virginia was not like most colonies. It was wealthier and more heavily populated than the other colonies, and huge by comparisonâlarger than every European nation except Russia and Turkey.

At the time of the First Continental Congress, Henry had studied Baron de Montesquieu's seminal work on government,

The Spirit of Laws

. The French political philosopher classed government into three categories: the republic, based on virtue; monarchy, based on honor; and despotism, based on fear. Liberty, Montesquieu wrote, was most likely to survive in small republics in which governors remain close to the governed and aware of their needs. “In a large republic,” he warned, “the public good is sacrificed to a thousand views . . . In a small one, the interest of the public is perceived more easily, better understood. ...”

8

Also essential to the survival of liberty, Montesquieu declared, was the separation of powers into

executive, legislative, and judicial branches, with the powers of each branch held by different individuals, acting independently of those in other branches, to prevent collusion.

The Spirit of Laws

. The French political philosopher classed government into three categories: the republic, based on virtue; monarchy, based on honor; and despotism, based on fear. Liberty, Montesquieu wrote, was most likely to survive in small republics in which governors remain close to the governed and aware of their needs. “In a large republic,” he warned, “the public good is sacrificed to a thousand views . . . In a small one, the interest of the public is perceived more easily, better understood. ...”

8

Also essential to the survival of liberty, Montesquieu declared, was the separation of powers into

executive, legislative, and judicial branches, with the powers of each branch held by different individuals, acting independently of those in other branches, to prevent collusion.

“The grand work of forming a constitution for Virginia is now before the convention . . . ” Henry wrote to John Adams, the man he most respected among delegates from other states he had met at the Continental Congress. “Is not a confederacy of our states necessary? If that could be formed, and its objects for the present be only offensive and defensive, and guaranty respecting colonial rights, perhaps dispatch might be had.” Adams sent Henryâ“as a token of friendship”âa pamphlet he had written entitled

Thoughts on Government,

9

with a plan for a democratic/ republican style government, which Henry “read with great pleasure. ...” In his letter of thanks, Henry warned Adams that unless Congress agreed on a plan for funding the Continental Army, “our mutual friend the General [Washington] will be hampered. ...”

10

Thoughts on Government,

9

with a plan for a democratic/ republican style government, which Henry “read with great pleasure. ...” In his letter of thanks, Henry warned Adams that unless Congress agreed on a plan for funding the Continental Army, “our mutual friend the General [Washington] will be hampered. ...”

10

“My Dear Sir,” John Adams answered Henry,

I had this morning the pleasure of yours. . . . Happy Virginia, whose Constitution is to be framed by so masterly a builder! . . . I know of none so competent to the task as the author of the first Virginia resolutions against the Stamp Act, who will have the glory with posterity, of beginning and concluding this great revolution. . . . I esteem it an honor and a happiness that my opinion so often coincides with yours. . . . It has ever appeared to me that the natural course and order of things was this: for every colony to institute a government; for all the colonies to confederate and define the limits of the continental constitution; then to declare the colonies . . . confederated sovereign states; and last of all, to form treaties with foreign powers. But I fear we cannot proceed systematically, and that we shall be obliged to declare ourselves independent states before we confederate, and indeed before all the colonies have established their governments. . . . We all look up to Virginia for examples.

11

11

After Henry published Adams's scheme of government in the

Virginia Gazette

, the Convention adopted most of it in principle, creating a bicameral

legislature with a popularly elected lower houseâthe House of Delegates, or Assemblyâand a Senate, or upper house, elected by members of the Assembly. The two houses were to elect a governor to serve as chief executive with consent of a privy councilâalso elected by the two houses. The two houses would also elect all other executivesâtreasurer, attorney general, and so forth. The governor would appoint all judges, with the advice and consent of the upper house.

Virginia Gazette

, the Convention adopted most of it in principle, creating a bicameral

legislature with a popularly elected lower houseâthe House of Delegates, or Assemblyâand a Senate, or upper house, elected by members of the Assembly. The two houses were to elect a governor to serve as chief executive with consent of a privy councilâalso elected by the two houses. The two houses would also elect all other executivesâtreasurer, attorney general, and so forth. The governor would appoint all judges, with the advice and consent of the upper house.

The Virginia Convention made a few minor changes, most of them based on the deep fears of executive tyranny implanted by George III's treatment of the colonies and the arbitrary powers imparted to colonial governors as the king's personal representatives. It limited the governor's term in office to one year and the length of time he could serve to three successive terms. After a hiatus of four years, he could serve a maximum of three more one-year terms. He could not legislate or rule by decree. Only the House of Delegates could originate laws, which the Senate would have to approve or reject for them to take effect. Despite Henry's objections, the Convention denied the governor the right of veto and the right to dissolve the legislature.

The Convention rejected “every hint of power which might be stigmatized as being of royal origin,” explained Edmund Randolph, then a delegate and later governor. “No member but Henry could with impunity to his popularity have contended as strenuously as he did for an executive veto. ... Amongst other arguments he averred that a governor would be . . . unable to defend his office from usurpation by the legislature . . . and that he would be a dependent instead of a coordinate branch of power.” In the end, however, “the Convention gave way to their horror of a powerful chief magistrate without waiting to reflect how much stronger a governor might be made for the benefit of the people.”

12

12

One addition Virginians made to the John Adams plan of government was mandatory voting, with fines for failing to vote. The convention limited voting privileges, however, to white, male freeholders with at least fifty acres of unimproved land, or twenty-five acres of improved land (cultivated, with a dwelling), or an improved lot in a town. Independence, in other words, did not change the “mental condition” of Americans, as an

English observer put it at the time. “Their deference for rank and for judicial and legislative authority continued nearly unimpaired,” and early state constitutions such as Virginia's kept voting powers in the hands of property owners and Christiansâdespite inclusion of bills of rights that seemed to empower all citizens.

13

English observer put it at the time. “Their deference for rank and for judicial and legislative authority continued nearly unimpaired,” and early state constitutions such as Virginia's kept voting powers in the hands of property owners and Christiansâdespite inclusion of bills of rights that seemed to empower all citizens.

13

As a preface to its framework for government, the Virginia Convention included a declaration of rights written by George Mason, who began with an affirmation that “all men are born equally free. ...” After delegates complained that the phrase gave blacks equal claims to freedom, old Edmund Pendleton resolved the arguments with an eight-word amendment that “all men are created equally free and independent

when they enter into a state of society

. . . .”

when they enter into a state of society

. . . .”

Among other rights, the sixteen articles guaranteed the “inalienable right to enjoy life, liberty, and happiness, the freedom of the press, the right to a speedy and fair trial before a jury, and the freedom of elections.” The sixteenth article asserted that “all men are entitled to the free exercise of religion. ...” and would lead to separation of church and state in Virginia in 1786. The articles prohibited excessive bail and fines, cruel and unusual punishment, imprisonment except by law or jury judgments, inheritance of public offices, and a standing army.

On June 29, the Virginia Convention adopted one of the first written constitutions in the Americas and proclaimed that “the government of this country [Virginia] as formerly exercised under the Crown of Great Britain, is TOTALLY DISSOLVED.” After George Mason placed Henry's name in nomination, the Convention elected Henry first governor of the newest, largest, and most powerful state in America, thus allowing him to fulfill his pledge to his troops to serve “the glorious cause” as a private citizen.

14

14

Virginia's declaration of independence came three weeks after Richard Henry Lee, Virginia's delegate to the Continental Congress, proposed the sweeping resolution that the United Colonies “are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States.” He also proposed that “a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective colonies for their consideration and approbation.”

15

15

On July 2, Congress adopted Lee's resolution, and on July 4, it approved a Declaration of Independence written largely by Thomas Jeffer-son

and to which John Hancock appended his bold signature as president of Congress. As Hancock was signing the Declaration, Patrick Henry was taking his oath as first governor of the free and independent Commonwealth of Virginia. In an evident response to criticisms of his coarse apparel, Henry laid aside his coarse country clothes before taking office. Breaking with his past, he crowned his head with an unpowdered wig and donned a costly black suit with knee breeches, overlaid by a scarlet cloak and other adornments that befitted the highest office in the new and sovereign Commonwealthâincluding a costly, ornate carriage.

and to which John Hancock appended his bold signature as president of Congress. As Hancock was signing the Declaration, Patrick Henry was taking his oath as first governor of the free and independent Commonwealth of Virginia. In an evident response to criticisms of his coarse apparel, Henry laid aside his coarse country clothes before taking office. Breaking with his past, he crowned his head with an unpowdered wig and donned a costly black suit with knee breeches, overlaid by a scarlet cloak and other adornments that befitted the highest office in the new and sovereign Commonwealthâincluding a costly, ornate carriage.

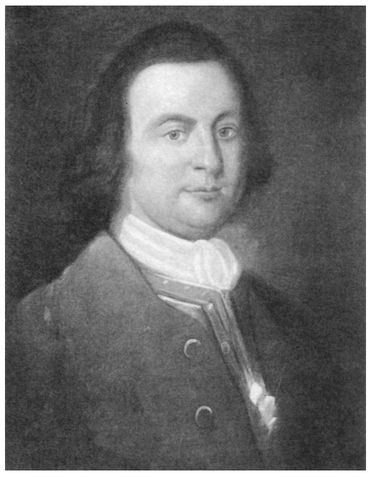

Planter George Mason was among the first members of Virginia's House of Burgesses to support a boycott of British goods after Parliament raised duties and sought to tax American colonists.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

“He had been accused by the big-wigs of former times as being a coarse and common man, and utterly destitute of dignity,” explained his son-in-law Judge Spencer Roane, “and perhaps he wished to show them that they

were mistaken.”

16

He apparently succeeded. From that time on, his friends and enemies addressed him as “Your Excellency” or “Your Honor.”

were mistaken.”

16

He apparently succeeded. From that time on, his friends and enemies addressed him as “Your Excellency” or “Your Honor.”

Almost all Virginians and, indeed, leaders in other states, hailed Henry's election. “Once happy under your military command,” wrote the officers and men of the First and Second Regiments that he had once commanded, “we hope for more extensive blessings from your civil empire . . . our hearts are willing, and arms ready to maintain your authority as chief magistrate. . . . ” Replying that “the remembrance of my former connection with you shall ever be dear to me,” Henry urged them, “Go on, gentlemen, to finish the great work you have so nobly and successfully begun. Convince the tyrants again, that they shall bleed, that America will bleed to her last drop, 'ere their wicked schemes find success.”

17

17

Henry's Quaker friends were equally elated that “the representatives of the people have nobly declared all men equally free,” and they proposed a plan for gradual emancipation of slaves. “I can but wish and hope,” wrote Virginia's Quaker leader Robert Pleasants, “that great abilities and interest may be exerted toward a full . . . confirmation thereof.”

18

18

In New York, meanwhile, the 10,000 British troops General Howe had evacuated from Boston landed unopposed on Staten Island. Ten days later, 150 British transports sailed into New York Bay and landed 20,000 more British troops and 9,000 Hessian mercenaries. Meanwhile, a second British fleet sailed within sight of Charleston, South Carolina, and rained cannon fire over Fort Moultrie on Sullivan's Island at the entrance to Charleston Bay. Instead of destroying the fort, however, the cannon balls embedded themselves in the soft palmetto logs of the fort's walls and strengthened themâindeed, made them all but impenetrable. When the fort's cannons returned fire, the British fleet had no choice but to sail away ingloriously, leaving the South free of British occupation for the moment.

With fewer than 20,000 men to defend the sprawling New York area, Washington desperately needed help defending Long Island. On August 16, Patrick Henry's former troopsâthe 700 men of the First and Second Virginia regimentsâbroke camp in Williamsburg and marched northward through the oppressive summer heat, with the Culpeper Minutemen carrying their rattlesnake flag, to which they had added Henry's words, “Liberty

or Death.” They reached Washington's headquarters on Harlem Heights in less than a monthâbut they were too late. Twenty thousand British and Hessian troops had stormed ashore in Brooklyn on the southwestern edge of Long Island and overrun the Patriot force of 5,000 defenders, killing 1,500 and capturing the American army's entire food supplyâalong with two American generals. Only a thick fog allowed survivors to escape in the dark of night across the East River to New York Island (Manhattan) on August 29.

or Death.” They reached Washington's headquarters on Harlem Heights in less than a monthâbut they were too late. Twenty thousand British and Hessian troops had stormed ashore in Brooklyn on the southwestern edge of Long Island and overrun the Patriot force of 5,000 defenders, killing 1,500 and capturing the American army's entire food supplyâalong with two American generals. Only a thick fog allowed survivors to escape in the dark of night across the East River to New York Island (Manhattan) on August 29.

After the Battle of Long Island, the British high command freed one of the captured American generalsâJohn Sullivan of New Hampshireâto go to Congress with a proposal for an informal peace conference. On September 6, Congress sent Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Edmund Rutledge of South Carolina to Staten Island to confer with Britain's military commanders General Sir William Howe and his brother Admiral Lord Richard Howe. After the usual preliminaries on September 11, the conference came to an abrupt end when the Howes insisted that the Americans renounce the Declaration of Independence as a condition for any further discussions.

Washington immediately posted the Connecticut militia to guard against a British landing at Kips Bay on the eastern shore of Manhattan Island and moved the main body of his troops to Harlem Heights, about six miles to the north.

19

Three days later, on the morning of September 15, five British ships in the East River began pounding American emplacements at Kips Bay with cannon fire. Within hours, 6,000 of the 8,000 Connecticut troops had fled. In disbelief, Washington galloped to the scene to rally the troops, but the slaughter on Long Island had left them so terrified they ignored Washington's orders. Officers and soldiers alike sprinted to the rear without firing a shot, leaving Washington and his aides exposed to possible capture.

19

Three days later, on the morning of September 15, five British ships in the East River began pounding American emplacements at Kips Bay with cannon fire. Within hours, 6,000 of the 8,000 Connecticut troops had fled. In disbelief, Washington galloped to the scene to rally the troops, but the slaughter on Long Island had left them so terrified they ignored Washington's orders. Officers and soldiers alike sprinted to the rear without firing a shot, leaving Washington and his aides exposed to possible capture.

Other books

Leap by M.R. Joseph

Hard to Serve: A Hard Ink Novella by Laura Kaye

Love Only Once by Johanna Lindsey

Private Dancer by Nevea Lane

Spellcrossed by Barbara Ashford

Sisters by Patricia MacDonald

Orphans of the Sky by Robert A. Heinlein

No Safeword: Matte - the Honeymoon by Candace Blevins

Stella Makes Good by Lisa Heidke

Keep: The Wedding: Romanian Mob Chronicles by Kaye Blue