Lionheart (27 page)

Authors: Douglas Boyd

Richard, with his fascination for all technology with military application, would certainly have known of this and required at least some of the ships to be equipped with compasses.

On 22 April they reached the island of Rhodes, which had been recaptured from the Muslims during the First Crusade,

16

but a third of the journey still lay ahead. On that day Philip was already being welcomed to the siege of Acre by his cousin Conrad of Montferrat after an uninterrupted voyage of twenty-two days from Messina, which indicates that he had enjoyed moderate favourable winds all the way. As Dr Gertwagen remarks:

Galleys of all kinds were poor sailers because they were designed to be rowed and could use their sails only with moderate breezes astern. Nor was the upwind performance of

naves

much better than that of galleys. Because of their rounded hull configuration and lack of deep keel, they made much leeway and with winds abeam it was difficult to hold a … course.

17

In fact, it was probably impossible to do so. The great advantage of galleys, of course, lay in calms when they could not only keep going on the right heading, but also tow becalmed vessels powered only by sail.

Richard’s crossing was very different from Philip’s. From Crete onwards, the seas were rough. Having suffered greatly from sea-sickness, he prolonged the stopover on Rhodes for ten days to take on provisions and especially fresh water, which was important for the horses, to exercise them a little and also to allow straggling ships to catch up. Fed on dry grain, with only stale water to drink while on board and their digestive systems upset by the motion of the ships, horses emerged from their stalls with problems that required several days of convalescence on land before the voyage could continue. Even more recuperative time would be needed on arrival in the Holy Land before the

destriers

would be fit for combat.

18

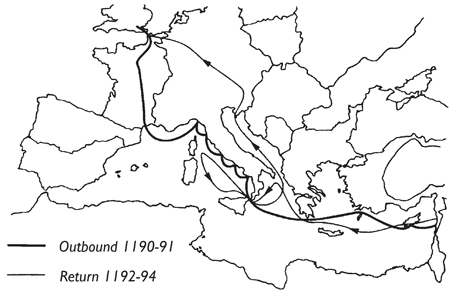

Richard’s routes on the Third Crusade

The third landfall may not have been intended, since the island of Cyprus lies less than 200 miles from Acre. In taking the Cross a crusader swore not to be deflected from the journey to Jerusalem for any reason. Yet the relief of Acre was unilaterally put on hold by Richard after another storm drove Joanna’s small convoy onto the coast of Cyprus. The

dromon

carrying her and Berengaria reached Limassol on the southern coast of the island, but the two escorting galleys were wrecked on shoals before reaching this haven and their cargoes impounded. The survivors of the wrecks were imprisoned on the orders of the tyrant Isaac Comnenus, who had seized power in 1184 and declared himself emperor of Cyprus. He instituted a reign of terror on the island after securing a niche within the balance of power of the eastern Mediterranean by signing treaties with William II on Sicily to the west and Saladin to the east.

Isaac refused permission for the

dromon

with its two royal passengers to moor in the calmer waters of Limassol harbour, hoping to oblige them to accept his offer that they should step ashore.

19

Refusing to be taken hostage so easily, Joanna replied to Isaac’s invitation with a polite apology, saying that she first needed her brother’s permission. In spite, Isaac refused supplies and even fresh water to her ship, but the number of armed men on board discouraged any further action.

On 6 May, five days after Joanna’s arrival, Richard’s fleet staggered into Limassol after another tempestuous crossing from Rhodes in which several vessels had been sunk and Richard’s

esnecca

narrowly missed the same fate. Foul-tempered from prolonged seasickness, he swore vengeance for the insults to his sister and Berengaria, and gave orders to trans-ship a landing force from the larger vessels into shallow-draught galleys and small boats to make for the shore, which had been fortified by Isaac and was defended by his troops. With Richard commanding a force of archers in the first landing craft, a hail of arrows fell on the defenders, giving the advantage to the invasion force. A great slaughter ensued, forcing the surviving defenders to flee inland and save their lives by taking paths through the mountains unknown to the crusaders.

20

Never one to let an enemy escape easily, Richard ordered horses to be disembarked and took advantage of the unpopularity of Isaac among the non-Greek merchant families of the port to hire guides, with which he pursued the Cypriot army, surprising its camp before dawn with such violence and bloodshed that Isaac fled in his night-clothes, leaving behind his treasury, tent, horses and even the royal seal. Next day, many of the Cypriot nobility came to the crusader camp and swore to support the king of England in his war against Isaac, giving hostages as witness of their good faith. Seeing himself thus abandoned, Isaac asked for and obtained a safe conduct to meet Richard, where he agreed to terms: a payment of 20,000 gold marks; the prisoners to be freed; and himself to join the crusade with 100 knights, 400 Turcopole mercenaries and 500 infantry. In addition, he ordained that supplies bought by the crews and passengers of the fleet would be duty free at fair prices. He also did homage to Richard, acknowledging him as overlord of Cyprus. Yet another example of the fate of women in those times was his gift of his daughter, for Richard to marry to whomever he chose.

It was a very satisfactory outcome for two days of combat – until Isaac took advantage of the camp being asleep and slipped away to what he thought was the safety of Famagusta on the eastern coast, despatching his wife and daughter to the fortress-port of Kyrenia (modern Girne in north Cyprus) and ordered the crusaders to leave his territory. On the same day a ship berthed in Limassol bringing Guy de Lusignan and a coterie of supporters including Humphrey of Toron to lobby Richard’s support in the political struggle with Conrad. Richard’s impulsive endorsement of Guy – who was generally considered dim-witted and lacking in princely authority – as the rightful king of Jerusalem was a knee-jerk reflex on hearing that Philip Augustus had given his support to Conrad.

Richard broke promises all the time, but decided to punish Isaac’s effrontery by conquering Cyprus after the new arrivals pointed out to him the strategic significance of the island. If it became a haven for crusading ships, so much the better; but if Isaac were allowed to make a firm alliance with Saladin, it could be used as a base for Saracen ships to intercept and capture Christian convoys bearing men, money and supplies to and from the Holy Land – which would spell the end of the Latin states.

Richard therefore divided his army into three regiments: one was to pursue Isaac overland and the balance boarded the galleys, whose number was swollen by five of Isaac’s galleys that had been taken as prize. These were divided into two flotillas, one under himself and the other under Robert of Turnham, to circumnavigate the island in both directions, in his words so that ‘this perjurer may not slip through my hands’.

21

In a time of no charts, the circumnavigation of an island beset by rocks and shoals was a hazardous undertaking that must have required pressing into service local seafarers as pilots and the use of the tallowed lead to ascertain the depth of water beneath the ships and the composition of the bottom when nearing shore. The mini-campaign was successful: every one of Isaac’s galleys and other ships encountered was taken as prize, and, seeing the crusader flotillas approaching, the castellans of Isaac’s littoral castles abandoned them and took refuge in the mountains.

22

Already feeling confident that he was the de facto ruler of Cyprus, Richard took a day off. On Sunday 12 May, Lent being ended, the 33-year-old king of England married Berengaria in the garrison church of St George at Limassol and then watched the bishop of Évreux crown her as queen of England. There was no shortage of bishops to perform the ceremony. No detail of Berengaria’s appearance was recorded by the celibate chroniclers, although the bridegroom is known to have been wearing a gorgeous rose-coloured

cotte

of samite, embroidered with glittering silver crescents, a scarlet bonnet worked with figures of birds and animals in gold thread, a cape decorated with shining half-moons in gold and silver thread and slippers of cloth of gold. His spurs and the hilt of his sword were of gold, and the mounts of his scabbard were silver. What his bride made of this display, which defied the austerity decreed for crusaders – or, indeed, of his penance in Sicily, where he had been flagellated publicly in his underwear before being given absolution for sodomy in order to take the sacrament at the wedding mass – is not recorded. Whether he ever shared her bed is unknown. There was in any case no issue.

Ignoring pleas from Philip Augustus to hasten to Acre with all possible speed and not waste time fighting Christians, albeit of the Orthodox rite,

23

Richard pursued Isaac to Famagusta, his army travelling partly on land and partly by sea. Isaac retreated to Kantara in the north of the island, placing his faith in the reputed impregnability of the fortress-port of Kyrenia and the castles of Kantara, St Hilarion and Buffavento, which, although ruined, are still impressive works of fortification today. The inland city of Nicosia was among those that surrendered without bloodshed. At some point Richard fell ill, probably from malaria, which had troubled him for years, leaving it to Guy de Lusignan to command the force that captured Kyrenia. Isaac’s queen and their daughter had taken refuge in the castle of Kantara, but when she saw the army approaching, the daughter came out to throw the castle, her mother and herself on Richard’s mercy.

Realising that all was lost, Isaac had fled to the furthest point on the island, at Cape St Andrew on the extremity of the Karpas Peninsula, where he finally surrendered on 21 May, pleading with his captors not to treat him like a common criminal by putting him in irons. As one king to another, Richard agreed, but had chains made of gold and silver before delivering his prisoner thus fettered as a hostage to the Knights of St John, who kept the self-appointed emperor of Cyprus confined at their castle of Margat in the principality of Antioch for three long years. Before sailing away, Richard entrusted the island to Robert of Turnham and Richard of Camville as regents in his absence.

Isaac’s daughter, who was referred to simply as

la demoiselle de Chypre

, joined Joanna and Berengaria for the rest of the voyage, arriving at the siege of Acre on 1 June and returning to Europe with them.

24

It was, for her, the start of an adventurous life that reads like the plot of a novel. After being bought from the Plantagenets as part of Richard’s ransom agreement negotiated in 1193, she was released – as was her father – into the care of Duke Leopold V of Austria, who was a distant relative of her branch of the Comnenus family. In 1199 she was recorded as living in Provence, where she met Count Raymond VI of Toulouse, who was then married to Joanna, the former queen of Sicily. Joanna was pregnant by Raymond for the second time but, shortly after what one supposes was a happy reunion with her erstwhile travelling companion, Countess Joanna was dumped by Raymond, who set up home with the Cypriot princess.

That did not last: in 1202 she married a bastard son of the Count of Flanders named Thierry, with whom she set sail, ostensibly on the Fourth Crusade. While the main body of the European crusaders forgot their sworn oaths and turned aside to sack the Christian city of Constantinople, thus destroying Europe’s bulwark against the Muslim Turks, the two adventurers headed for Cyprus with the ambition of reclaiming Isaac Comnenus’ realm in the name of his daughter. In the interim Richard had, although briefly styling himself ‘king of Cyprus’, sold the island to the Knights Templar for 100,000

bezants

, 40,000 down and the balance on a mortgage. Unfortunately, the Templars’ rule of the island proved as unpopular as Isaac Comnenus’ had been, the heavy taxation of the islanders causing a series of uprisings. These culminated in Nicosia on 5 April 1192, when the Templars were forced to take refuge in the citadel, emerging to beat off their attackers in a savage combat in which they narrowly missed being wiped out. Wisely, they returned the island to Richard, who sold it again – to Guy de Lusignan, the exiled king of Jerusalem, under whose descendants it knew comparative peace and prosperity for many years. The impromptu invasion by Isaac Comnenus’ daughter and her lover failed dismally. They were last reported seeking asylum in Armenia.