Listening In (5 page)

Authors: Ted Widmer

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

PHOTOGRAPHIC CREDITS

FOOTNOTES

BY CAROLINE KENNEDY

All my life people have told me that President Kennedy changed their lives—they decided to join the Peace Corps, run for office, volunteer in the inner city or outer space because he asked them to—and convinced them that they could make a difference.

The generation he inspired changed this country—they fought for Civil Rights, women’s rights, human rights, and nuclear disarmament. They passed that inspiration down to us—their children and grandchildren. As the first truly modern president, my father redefined America’s timeless values for a global audience, and asked each individual to take responsibility for making this a more just and peaceful world.

As we mark the fiftieth anniversary of his presidency, my father’s time is becoming part of history rather than living memory. Yet President Kennedy’s words, his example and his spirit, remain as vital as ever. At a time when young people are often disillusioned with politics, we need to reach across the generations and recommit ourselves and our country to these ideals.

During times of uncertainty like the present, the future appears threatening and the challenges to our nation can seem almost insurmountable. Yet history reminds us that America has faced difficult and dangerous times before—and that we have triumphed over them.

Listening to these tapes now is a fascinating experience because historical perspective informs our understanding of events that were unfolding in real time for the participants. Moreover, many of the issues that defined that tumultuous time—racial justice, economic fairness, and foreign intervention—continue to dominate our national debate today. Studying a legacy of strength in the face of conflict and examining the leadership of past administrations, we can identify warning signs, critical turning points, and guiding principles that can help us deal with current crises.

I was always told that my father installed secret Oval Office recording devices after the Bay of Pigs disaster so that he could have an accurate account of who said what, in case of any later disputes as to the exact nature of the conversations. And as an avid reader of history, and a Pulitzer Prize–winning author, he intended to draw upon this material in his memoirs. The full 265 and a half hours of tape-recorded conversations that have now been made available by the Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston provide insight into the magnitude, the complexity, and the range of issues confronting a president on a daily basis. They also give a sense of the human side of the presidency—the exhilaration, the frustration, and the sense of purpose that were part of my father’s commitment to public service.

The unedited conversations are fascinating but somewhat difficult to decipher and navigate. The sound quality is often poor, and at times it is hard to figure out who is talking. Our family and the Kennedy Library are committed to making the record of my father’s presidency widely accessible, so we decided to compile significant excerpts and make them easily available to the public.

We are fortunate to have Ted Widmer as our editor and guide through this material. A historian with a comprehensive knowledge of the historical and the modern presidency, Ted also served as a speechwriter to President Clinton, edited the Library of America’s two-volume anthology of American speeches, and has written numerous books and articles on American history. We wanted this collection to include the most significant moments caught on tape, as well as snippets of conversation that give insight into the President’s mind at work and the human qualities that made him who he was: serious, purposeful, curious, skeptical, impatient, probing, principled, amused. Ted has done a masterful job of listening, transcribing, selecting, and illuminating this audio record.

As always, I am deeply grateful to the archivists and staff of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum and the entire National Archives, who preserve, catalogue, archive, and study the documents, tapes, films, memorabilia, and ephemera that form the stuff of history. Their dedication and their commitment to excellence is something all Americans should find inspiring.

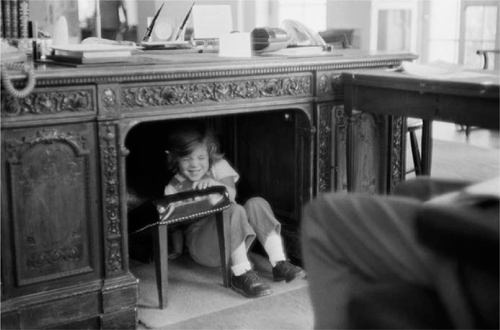

For me, listening to these conversations is a powerful experience. Although at the time, I was too young to understand much of what was happening, I recall spending happy afternoons eating candy and making paper-clip necklaces under my father’s desk while men talked in serious voices. The delight in my father’s voice when my brother and I appear is something I treasure.

CAROLINE HIDING UNDER THE HMS

RESOLUTE

DESK IN THE OVAL OFFICE, MAY 16, 1962

I especially hope young listeners will find these selections interesting enough that they will want to further study the Kennedy presidency, and I trust that those who remember these times will gain new perspective. I hope that people will be drawn into the drama and the daily routine of the presidency, that they will feel they have learned something about the kind of person my father was, and most of all, I hope they will be inspired to serve our country as he did.

PRESIDENT KENNEDY CONFERS WITH SECRETARY OF DEFENSE ROBERT MCNAMARA AND GENERAL MAXWELL TAYLOR, CHAIRMAN OF THE JOINT CHIEFS OF STAFF, JANUARY 25, 1963

BY TED WIDMER

“Mythology distracts us everywhere,” John F. Kennedy said on June 11, 1962, in a speech at Yale University. Kennedy had spent a good deal of his life debunking the mythologies he encountered. As a senator, he gave important speeches questioning the binary logic of the Cold War in remote theaters like Vietnam and Algeria. As a historian, he was attracted to the lonely few inside Washington’s political establishment who possessed the courage to think for themselves. Fresh out of college, he struck closer to home by criticizing the pacifistic idealism of the British leaders who failed to prepare their nation for war in the 1930s. That latter stand included an implicit rebuke of his father, Joseph P. Kennedy, which seems not to have fazed their relationship in the slightest.

A month after the Yale speech, he struck back at mythology yet again. To avoid inaccuracy and possibly worse, Kennedy was determined to have a reliable record of the words that were spoken in the White House. And so in July 1962, Secret Service agents installed a sophisticated taping system in the Oval Office and Cabinet Room of the White House. The reasons for the installation were never explained, by Kennedy or anyone else; in fact, the very existence of the taping system was a closely held secret, communicated to a tiny number of people. The President’s secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, knew; her assistance was required to operate the system and maintain the tapes. Robert Kennedy probably knew; it is difficult to believe that he did not, and he used the tapes a few years later to write his memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis,

Thirteen Days

. But we simply do not know for sure.

The result, however, is not a mystery at all. It is a fact of the highest significance. A vast amount of information was gathered by those recording devices—248 hours of meetings in the Oval Office and Cabinet Room, and 17 and a half hours of telephone conversations and dictated private reflections. They constitute a historical trove of extraordinary consequence. They shed insight into all of the policy decisions of the Kennedy administration, as they were arbitrated at the highest level. And they offer a precious insight into something elusive—how a presidency actually

works

. Minute by minute, we get a sense of what it feels like to occupy the most important office in the world—and likely the loneliest. Earlier presidents had dabbled in taping—Kennedy’s three predecessors, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman, and Dwight D. Eisenhower, had all put a few meetings on tape. But Kennedy’s new initiative was on a vastly different scale.

The agent who installed the taping system, Robert Bouck, recorded an oral history in 1977 that shed some light on the devices, although his memories had already become somewhat hazy. Bouck’s responsibilities included the protection of the President from electronic surveillance, so he was a logical person to ask to improvise a new recording system for the private use of the President himself. Accordingly, he placed a microphone in the kneehole of the famous HMS

Resolute

desk and another, disguised, on the coffee table between the two sofas where the President sometimes sat with visitors. Kennedy could activate the device with a push button under his desk. According to Bouck, “It looked just like a button you’d press to signal your secretary—like a buzzer button.” Kennedy also had a button on the coffee table, near the chairs where he would sit for more relaxed conversation.

In the Cabinet Room, the microphones were in two spots on the wall where there had once been light fixtures, now covered by draperies. By his place at the table, President Kennedy had another switch to activate recording. The microphones were fed into a Tandberg reel-to-reel tape recorder, whirring in a basement room used by Evelyn Lincoln for storage. Bouck would change the tapes as needed. He believed that Evelyn Lincoln also had the capacity to initiate recording, but he could not remember with certainty. Not long after the installation of the system, Kennedy significantly expanded the operation by creating a separate system that would record his telephone calls. These calls, recorded on Dictaphone belts (also called Dictation Belts or Dictabelts) add real meaning to the record and are generally recorded with higher sound quality. The telephone and Dictabelt recording devices were installed separately, and there is no record of why they were set up. Bouck believed that the President also was able to record inside his private living quarters, but that fact has never been established with authority, and the existing tapes do not corroborate it.

Unfortunately, Bouck was relatively mute on a key question—

why

did President Kennedy suddenly want a record of his conversations in July 1962? Tentatively, Bouck essayed an answer—that “the tensions with the Russians were kind of great during that period, and I think initially his concern was to record understandings that might have been had in those relations.” There are grounds for this theory—during the Bay of Pigs episode of April 1961, Kennedy received a great deal of inaccurate information from the planners of the operation, including the CIA and the Joint Chiefs, and it would certainly have been useful for him in the future to have these bland predictions of success on record. During an interview she gave to

Newsweek

in 1982, Evelyn Lincoln speculated that the Bay of Pigs was the reason for the tapes.