Listening In (8 page)

Authors: Ted Widmer

J

ohn F. Kennedy may have been the youngest president elected and a supreme modernist in a modernist age, but he also possessed an acute sense of his nearness to the American past. He invited historians to work and speak in the White House, and unlike most presidents, he formally joined the fraternity by enlisting in the American Historical Association, as Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson had before him. He read widely in British and American history and wrote with surprising breadth for a hard-charging politician.

Profiles in Courage

explored the great and not-so-great with an impressive disregard for the big names guaranteed to sell a book in 1957—Lincoln or Jefferson or Washington. Instead, Kennedy chronicled the little known (who ever heard of Edmund Ross?) along with the well known but not especially well liked (Daniel Webster) and, surprisingly, made a best-seller and a Pulitzer out of it all.

But

Profiles

was only one point of entry into history. It is a commonplace to lament that Kennedy did not live a longer life, but what is remarkable is how much he saw and achieved in the time that was allotted to him. He witnessed Germany writhing under the madness of Nazism on the eve of the war and attended the anguished debates in Parliament as England wrestled with the vexing question of how to respond to Hitler. He famously served in a distant Pacific outpost of the global conflict that ensued, and in the spring of 1945, as a cub reporter, he covered the San Francisco conference that launched the United Nations and painted a more hopeful vision of the world to come. A month later, he walked through the ruins of Berlin with the secretary of defense and the supreme commander of the Allied Forces in Europe, Dwight D. Eisenhower. All of this took place before he launched his political career in 1946.

Despite the newness so palpably in the air in the 1960s, history colored all of the great events of the Kennedy presidency. Without a doubt, the centennial of the Civil War gave additional urgency to the Civil Rights Movement and even to the geopolitical situation (Kennedy called the Cold War “a global civil war”). The waste and carnage of World War I were not all that far from memory, and in 1962, Kennedy was so taken by Barbara Tuchman’s

The Guns of August

that he ordered it sent to military installations around the country. That book, which explored the question of how self-destructive wars are started, could not have been more appropriate on the eve of the Cuban Missile Crisis. And of course, World War II was the experience that unified everyone in the upper reaches of political life, in the United States as well as abroad.

Inevitably, John F. Kennedy’s sense of history seeped into the conversations that he recorded. Two remarkable tapes from early 1960 reveal that he was thinking deeply about the circumstances of his life, from primal forces to small accidents of fate, that were leading him to grasp for the great prize in American politics. One of the tapes records him parrying good-natured questions from a group of friends at a Georgetown dinner party, the other dictating more serious reflections on his life. This may have been the natural instinct of a candidate to set the record straight, or to convey a sense of his origins to the American people—much as Lincoln had issued a short autobiographical sketch when he ran a century earlier. But it seems more likely that Kennedy was contemplating a memoir of some kind, a book (to be written later) that he often mentioned in the White House. These conversations take us closer to that book than one might expect.

On October 3, 1961, Kennedy greeted a group of historians who had issued a set of the papers of John Adams, the first occupant of the White House. Revealingly, he told them, “Some of us think it wise to associate as much as possible with historians and cultivate their good will.” Then, with typical irreverence, he added that he liked the approach of Winston Churchill, who predicted that history would treat him gently, “because I intend to write it.”

That was tongue-in-cheek, of course; Kennedy admired the skepticism of the historical fraternity he had joined, and knew that he would inevitably be judged by them after leaving office, in ways that were beyond his control. He said as much at Amherst College in October 1963, when he praised those who question power, “for they determine whether we use power or power uses us.” Clearly, he wanted to tell his part of the story. The tapes offer a beginning.

RADIO INTERVIEW, ROCHESTER, MINNESOTA, 1940

Kennedy published his first book,

Why England Slept

, in 1940, the year that he graduated from Harvard College. A study of England’s failure to increase defense spending in response to the rise of Nazism, it showed a serious grasp of international affairs, and its call on the United States to prepare for war flew in the face of many of the pronouncements of his father, former ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy. Nevertheless, Ambassador Kennedy was instrumental in supporting the book’s publication, and a range of influential opinion-shapers praised the new work, including the greatest of them all, Henry R. Luce, the force behind

Time

and

Life

. Exactly one radio interview survives from the media blitz, a recording made from a station in Rochester, Minnesota, featuring a very young author not long out of college.

ANNOUNCER:

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. At this time, we are indeed pleased to have with us in our studios Mr. John F. Kennedy, son of Ambassador and Mrs. Joseph P. Kennedy, who is in our city visiting Dr. and Mrs. Paul O’Leary. Mr. Kennedy is the author of the recently published book,

Why England Slept....

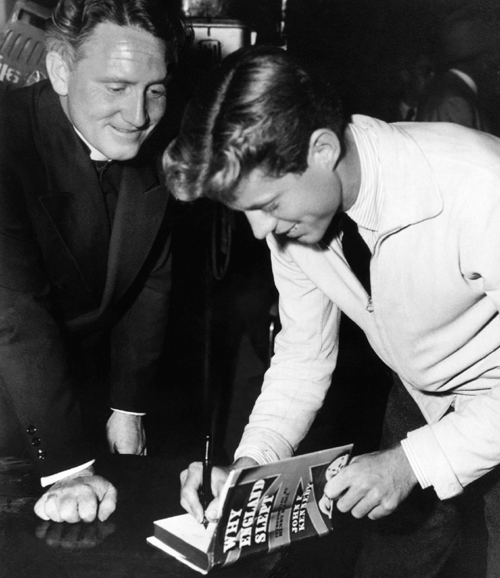

JFK SIGNING A COPY OF HIS BOOK

WHY ENGLAND SLEPT

FOR ACTOR SPENCER TRACY, NOVEMBER 1940

[break]

This young man from Boston has a clear-headed, realistic, unhysterical message for his countrymen, and for his elders. And with that, we want you, too, of the radio audience, to meet Mr. John F. Kennedy, who is known to his friends as Jack Kennedy. But first, before we get into questions about this much-discussed book, I’d like to ask a few questions about how our guest has spent some of his twenty-three years. Tell me, Mr. Kennedy, where did you go to school?

JFK:

Well, I attended Harvard, I just finished there this June.

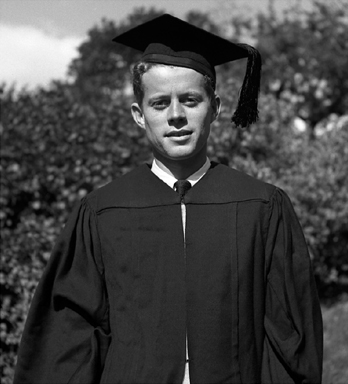

JFK AT HIS HARVARD GRADUATION, 1940

ANNOUNCER:

And what are you studying at the present time?

JFK:

Well, I studied international relations there, and I plan to go on to law school the next three years, and study law at Yale University.

ANNOUNCER:

And may I ask what are your plans for the future?

JFK:

Well, I don’t know exactly yet. I’m interested more or less in working sometime in my life for the government, but I haven’t really decided as yet.

In the pre-television age, songs were more essential to campaigns than now, and a small number of recordings preserve music from the early Kennedy campaigns. This selection, from the 1952 Senate race, in which Kennedy defeated the incumbent, Henry Cabot Lodge, offers a robust set of rhyming reasons for a Kennedy vote.

When we vote this November,

Let’s all remember,

Let’s vote for Kennedy!

Make him your selection,

In the Senate election,

He’ll do more for you and me!