Long Road Home: Testimony of a North Korean Camp Survivor (16 page)

Read Long Road Home: Testimony of a North Korean Camp Survivor Online

Authors: Yong Kim,Suk-Young Kim

Tags: #History, #North Korea, #Torture, #Political & Military, #20th Century, #Nonfiction, #Communism

“What a bitter cigarette! Terrible taste! Pew! Hey you, come here and clean this!”

He would throw a perfectly fine cigarette on the floor and walk out. The cigarette had just been lit and was still burning. The appointed prisoner would immediately jump on it and puff away the heavenly bud while others intensely watched the orange flame and smelled the air with fathomless envy. Guards were not supposed to stay with one work unit too long so that they wouldn’t develop any personal attachment to particular prisoners or possibly the entire unit. If the guards detected any humane connection between their colleagues and prisoners, they would report it to their superiors. And the next day every guard would be rotated to take charge of another work unit.

Mother

One day during work I was summoned by a guard. My heart sank. Was this the end of my dismal existence at last? Other prisoners must have thought that I was doomed like so many others who were summoned, never to return. I got in a container and ascended to the outside of the mine shaft. The brilliant sunlight overwhelmed me. For the two years I’d been at Camp No. 14, I hadn’t seen any sunlight except during the brief road construction project. My entire body was itchy and dripping pus for lack of sun. My face must have looked simply awful. As I was facing the sun, tears kept flowing from my eyes. I finally made out a four-wheel-drive vehicle parked in front of the entrance to the mine. The guards ordered me to get in. Riding in the car, for the first time in two years, I had a bird’s-eye view of the camp from farther up the valley. The car came down to the main area of the camp and the guards took me to a reception area, quite similar to where I’d been checked in two years before. Many more guards were waiting for me, unfamiliar faces, definitely not the guards from this camp. Out of habit, I kneeled on the floor and lowered my head. One guard who looked like a leader said, “Do you know why you are here?”

I had no answer. I really had no idea. But I knew for sure that I wouldn’t be executed; otherwise, they would not have brought me here to the office.

“Read this form and sign it. It’s very important for your own security.”

The form he gave me said that I could not divulge any information about Camp No. 14 to anyone in any form of writing or speech. The head of the guards threatened in a low, coarse voice that if I opened my mouth, I would be dragged back to the camp and beaten to death like a stray dog. I immediately signed the paper, avoiding eye contact with the guards.

“The Great Party generously considered your case and decided to bestow clemency, so that you could move on from Camp No. 14.”

I simply could not believe my ears. My entire body was numb with shock. For a few minutes, I thought that I was excused of my charges and was to be released. I could not believe that I was leaving this hell. I was so carried away that I prostrated in front of Kim Jong-il’s portrait and hailed him with what little strength was left in me. “Long live the Dear Leader! Long live the Dear Leader! Long live the Dear Leader!” The guards did not stop me and let me go on until I ran out of breath.

When I was done paying my profuse tribute, the unfamiliar guards ordered me back to the car again. We drove for some time and I saw that we were crossing a bridge over a river. Then to my surprise, I saw a large iron gate. I felt like my head had been struck by a hammer. I knew better than to think that they would let me walk away from Camp No. 14 alive, but I’d been so shocked to hear the announcement that I lost my judgment temporarily and assumed that I was being set free. Of course, that never could have happened. What would happen to me now? The car drove through the iron gates and the guards took me to a reception area, where there were not only local security guards but also guards from the Pyongyang National Security Agency. Having been a part of that organization, I immediately knew that the NSA guards had been dispatched from the capital. There was also an old woman in rags quietly sitting in the corner. She looked completely frozen, as if she wasn’t breathing. When I entered the room, one of the guards pushed my back, steering me toward the old woman, and asked, “Hey, aren’t you glad to see your mother?”

Mother?

How strange that name sounded in that bizarre moment. I did not know what to say.

All I saw was a crooked face covered with wrinkles and multiple traces of indescribable suffering. Her skin was so thin and dry that it looked like a worn-out rag covering her protruding cheekbones. Her thin gray hair barely covered her tiny head, making it look like a skull with corn silk patches stuck on here and there. The old woman’s dull eyes were gazing at me like I was a stranger. She was at a loss. I cannot rationally explain, but instead of feeling glad or surprised to see her again, I just felt incredible resentment toward this strange old hag.

“Stupid cow, don’t you realize that it’s your son?” one of the guards reprimanded her.

She lifted her head a bit and kept looking at me blankly.

I could see that the guards were looking at each other and exchanging signs. The ones from Pyongyang were also noticing the obvious lack of familiarity between the old woman and me. Later I realized that it was their final test to see if I had really been involved in my mother’s conspiracy to forge my identity. Having confirmed what they probably knew already—that I had not had any substantial contact with my mother ever in my life—the officers left the room. The local guards shoved us to the exit and yelled coarsely, “You will be allowed to live with your mother from now on. Now both of you are dismissed.” That was how I was suddenly transferred to Camp No. 18 and unexpectedly reunited with my birth mother.

When the guards released us, Mother led me to her quarters. Her gait was heavy and slow. She neither looked at me nor talked to me. She opened the door of a shabby hut made of corn stalks and mud. I could see the exposed stalks where dried mud had fallen out. The hut would collapse if there were a strong storm. The floor was exposed ground, nothing covering it. In a corner of the hut was a small kitchen where a steel pot and a broken bowl were the only household items. This was where Mother had been living ever since she’d been arrested. When we were left to ourselves, we sat in silence. Strangeness lay between us. She kept looking at me from the left, then from the right, and then left, and repeating the process. Her eyes welled up with tears, which rolled down her cheeks in streams. I felt that tyrannical fate was leading me through a tumultuous spiral where I could not see an inch ahead. My head was spinning, and I lay down on the floor and fell asleep without understanding the meaning of it all.

That night, I woke up to find my face covered with tears. When I opened my eyes, Mother was looking down at me. A fresh tear fell on my face. A strange and sore sensation came over me and I gazed into her eyes.

Both of us were speechless, but there was an emotional rapport when our eyes met.

“Mother …” I responded to her teary gaze in a low voice.

Mother.

It was the name I’d longed for all my life, the word that I had wanted so badly to pronounce, without any pretense or doubt. There was the mother I’d craved in the days at the orphanage. Then followed an adoptive mother who did not love me. And now in front of me was the mother I had lost, unknown to me, for a reason larger than any of us.

We both could not sleep that night. Mother broke her silence and started to tell me about the past. About the father I had never known, about how Uncle took risks to save my life, how she regretted it after she gave me up at the orphanage, how she wondered about me all her life. We sat and talked; we talked and cried; and when we cried together, we understood each other. Mother told me that my father was a talented mechanic and traveled frequently to Seoul as a peddler. When the Korean War broke out, he became the village chief of the Self-Defense Corps and killed many communists. When the South Korean Army and the allies marched up north, he facilitated their advance. She wasn’t sure if he really worked for the CIA, but as far as she knew, it was true that he worked under the command of a U.S. Army officer.

Thus began two and a half years of my life with Mother at No. 18. Being with her made everything bearable. Whenever I had spare time, I would go up the hillside and collect any edible weeds for her, and she in turn would also collect anything edible to feed me. In the beginning I did not know that she was saving a major part of her ration for me. She thought she could get by with less food because she did manual labor, whereas I kept working in a coal mine. Everyone in No. 18, young or old, had to work. My mother’s work was to weave plant material for carts and make brooms. Whenever I noticed that she was not eating, she would say that her old body couldn’t digest coarse food. Prisoners in No. 18 ate half of what normal people would eat. We had to survive for ten days on a portion that normal people would consume in five days. Our main diet consisted of dried cornmeal boiled with any edible grass we managed to collect. So when Mother cut back on what was already a meager portion, it must have rapidly weakened her. But she was only too glad to put up with perpetual hunger for her only surviving child. For the first time I experienced unconditional maternal love. Her love was strong and pure; it defied any doubts or fears.

Camp No. 18

Compared to No. 14, No. 18 felt like heaven. By 7:00 a.m., all prisoners were required to sign in at their workplace, whereas in Camp No. 14, everyone was at work by 5:30 a.m. At No. 18, prisoners could live with their family in a single hut. No matter how dilapidated the living quarters might have been, it was humane to live with one’s family. No matter how hungry the prisoners might have been, they could at least be with their family members. At Camp No. 14, sixty male prisoners slept together piled on top of one another in a small barrack. There, prisoners were not given any freedom to move around the camp, while in No. 18, they could climb up the mountain to a certain level and gather grass to supplement their diet. The only rule was that they had to return to the camp by a certain hour. For this reason all the bark on the pine trees in that area had been consumed by starving prisoners. If the guards caught inmates collecting bark, they were punished for damaging state property. If the prisoners were caught three times, they would be executed for their intention to destroy state property. Nevertheless, they risked their lives, scrambling to get their hands on anything edible. Although Camp No. 18 was a lot better than No. 14, I still witnessed so much brutality—death by starvation and public executions prevailed.

A close-up satellite image of prisoner housing in Camp No. 14. Kim Yong was confined in one of these barracks, approximately 10 yards by 6 yards, with some 60 other male prisoners.

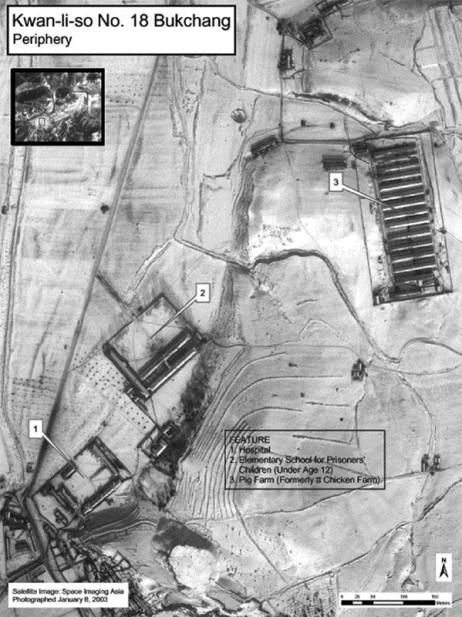

A close-up satellite image of Camp No. 18, featuring an elementary school, a pig farm, and a hospital.

Only much later did I learn that my former supervisor D had filed for clemency on my behalf, which must have been risky for him. He must have argued that I was sent to the camp not because of the crime I had committed myself, but because of what my parents’ generation had done. In other words, I was not the “first generation of wrongdoers,” as they would put it in North Korea, but the “second generation” imprisoned for my parents’ crime; therefore, D had a chance of appealing for my transfer. Besides, I had been perfectly loyal to Kim Jong-il and his regime before imprisonment. Because Camp No. 18 was less ghastly than No. 14, the second and the third generations of wrongdoers were usually detained there. The original “wrongdoers”—the first generation—and the second generation were often executed immediately upon their arrest; the third generation was sent to No. 18, where the fourth generation was born. In principle, prisoners did not have the right to bear children at the camp. But because family members lived together, women occasionally became pregnant. Many were forced to have an abortion at an early stage. I heard stories about how the guards injected salty water into pregnant women’s wombs and dug out the fetuses with spoons. It was not a secret that starved inmates would eat aborted fetuses instead of discarding them after the “surgery.” But some women who were discovered too late to have an abortion managed to give birth at the camp to a generation of people who knew no life beyond the walls topped with barbed wire. They were detained there for having been born into a family of “criminals.” However, because they had not committed a crime of their own, they did relatively easy work, such as working in the distillery or feeding the pigs, where they could scavenge food scraps to fight starvation. Guards poured night soil into the animal feed so that the prisoners would not steal it, but this failed to deter them from drinking and eating whatever was in the pigsty. When the pigs gave birth, usually to ten or twelve piglets at a time, the prisoners working there would steal two or three and put them in a boiling food pot. Then they would secretly have a sumptuous feast, unimaginable by any camp standards. They ate not only the tender meat but also everything else—skin, feet, eyeballs, and ears.