Lost at School (7 page)

Authors: Ross W. Greene

His teachers also feel that when Rodney senses weakness or vulnerability in a classmate or teacher, he “goes in for the kill.” One of his classmates commonly erupts when Rodney whispers things, out of earshot of the teacher, that he knows will upset her. One teacher tells the story of a shy, timid kid who was formerly in Rodney’s science class. Rodney verbally tormented the student so relentlessly that he eventually transferred out of the class in order to escape him.

Rodney’s teachers report that trying to talk with him about these issues is an exercise in futility. Reports one teacher, “He won’t talk. He always changes the topic. And if you press him on something, he just gets up and leaves the room.”

When Rodney’s teachers completed an ALSUP, they endorsed virtually every item, including the following:

• Difficulty expressing needs, thoughts, or concerns in words

• Difficulty empathizing with others and appreciating another person’s perspective or point of view

• Difficulty maintaining focus for goal-directed problem-solving

As regards unsolved problems, they prioritized the following:

• Being corrected or reprimanded for using profanity

• Being corrected or reprimanded for his mistreatment of classmates

• Whenever you don’t watch him like a hawk

ILLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES

Before moving on, let’s consider in greater detail why common interventions are not terribly effective. Kids learn how we want them to behave because we tell them. In the case of challenging kids, it’s not that they don’t know how we want them to behave, it’s that they’re lacking the skills to execute what they know. You may want to catch yourself the next time you’re on the verge of asking a kid “How many times do I have to tell you …?” Instead, figure out why he’s having such difficulty consistently acting on what he knows—in other words, identify the skills he’s lacking—and pinpoint the specific situations (unsolved problems) in which those lacking skills are causing the most trouble.

But that’s not what usually happens. Instead, the kid gets those powerful, inescapable,

natural

consequences: praise, approval, being scolded, being disliked, not being invited to things, and so forth. Challenging kids experience lots of natural consequences, though they’re likely to experience the punishing variety far more often than their less challenging counterparts. Natural consequences are effective at reducing the challenging behavior of some kids, but not the kids this book is about. That’s because natural consequences don’t solve the problems or teach the lagging skills that are precipitating their challenging behavior.

So the challenging behavior persists, or worsens. In response, adults usually add even more consequences, those of the imposed, “logical,” “unnatural,” or “artificial” variety. These include punishments such as staying in from recess, time-out from reinforcement, detention, suspension, and expulsion; rewards such as special privileges; and record-keeping devices such as stickers, points, levels, and the like. A word of caution on referring to such consequences as “logical”: If a kid hasn’t responded to

natural

consequences, then simply adding imposed consequences may not be very logical at all! Imposed consequences don’t solve the problems or teach the lagging skills that are precipitating challenging behavior, either.

These kids clearly need something else from us. They need adults who know that lagging skills give rise to challenging behavior and that such behavior occurs under specific conditions. They need adults who can identify those lagging skills and unsolved problems and know how to solve those problems (collaboratively) so that the solutions are durable, the skills are taught, and the likelihood of challenging behavior is significantly reduced.

And yet, the debate is a common one: Is it that the kid

can’t

do well or

won’t

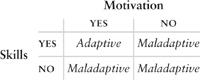

do well? If he can’t do well, then lagging skills are the logical explanation. If he won’t do well, then poor motivation would seem to make sense. Things are seldom so simple, but here’s a graphic that might help you think this through; it shows the different combinations of motivation and skills and their logical outcomes:

If a child has the requisite skills and is motivated (Yes/Yes), we should expect to see adaptive behavior. If a child does not possess the requisite skills and is not motivated (No/No), we are unlikely to see adaptive behavior. And if a child does not possess the requisite skills and is motivated (No/Yes), adaptive behavior is also unlikely. Which brings us to the fourth possibility: Yes Skills/No Motivation. Many adults believe they see this combination most often; that’s why motivational strategies are so popular. However, I’m not sure I’ve ever seen it. When people make use of the ALSUP, they find that kids who they thought were unmotivated were, in fact, lacking lots of skills. In other words, when adults change their understanding of challenging behavior, things finally begin moving in the right direction.

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this chapter, so a summary of the key points might be helpful:

• Viewing challenging behavior as the result of lagging skills (kids do well

if they can

) rather than as poor motivation (kids do well

if they want to

) has significant ramifications for how adults interact with kids with behavioral challenges and try to help them.

• A wide range of lagging skills can set the stage for challenging behavior.

• Challenging behavior usually occurs in predictable situations called unsolved problems.

• Adults have a strong tendency to automatically apply consequences to challenging behavior. Whether of the natural or artificial variety, consequences do not teach lagging cognitive skills or help kids solve problems.

• The first step in helping a challenging kid is to identify the skills he’s lacking and the problems that are precipitating his challenging moments, and this is best accomplished by having relevant adults use the ALSUP as a tool for achieving a consensus.

Q & A

Question:

If lagging cognitive skills and unsolved problems set the stage for social, emotional, and behavioral challenges in kids, what is the fate of the functional behavior assessment (FBA) routinely performed in schools to better understand challenging behavior?

Answer:

For the unfamiliar, an FBA (sometimes called a functional analysis) is a procedure through which the function (causes, purposes, goals) of a kid’s challenging behavior is identified. Though FBAs are common in schools, the information gathered through and inferences drawn from a functional analysis vary depending on the orientation, training, and experience of the evaluator conducting the procedure.

But a core assumption guiding most FBAs is that maladaptive behavior is “working” for a kid by allowing him to “get” something desirable (e.g., attention, peer approval) or “escape” or “avoid” something undesirable (e.g., a difficult task). The belief that challenging behaviors are somehow “working” for a kid leads many adults to the

conclusion that those behaviors are purposeful (what could be referred to as the

intentionality attributional bias

). This popular conclusion can set the stage for misguided statements such as “It must be working for him or he wouldn’t be doing it,” and invariably sets the stage for interventions aimed at punishing kids’ challenging behaviors so the behaviors don’t “work” anymore, and rewarding adaptive replacement behaviors to encourage ones that “work” better. This is the foundation of most school discipline programs.

But this definition of “function” reflects what I call the “first pass” of a functional assessment. There’s an indispensable “second pass”—a deeper level of analysis—that, regrettably, often goes neglected. And that is:

What lagging skills help us understand why the kid is getting, avoiding, and escaping in such a maladaptive fashion?

The second pass begins with some very important questions: If the kid had the skills to go about getting, escaping, and avoiding in an adaptive fashion, then why is he going about getting, escaping, and avoiding in such a mal-adaptive fashion? Doesn’t the fact that he’s going about getting, escaping, and avoiding in a maladaptive fashion suggest that he doesn’t have the skills to go about getting, escaping, and avoiding in an adaptive fashion? These questions spring from the core mentality of the CPS model (kids do well if they can) and from the belief that doing well is always preferable to not doing well (but only if a kid has the skills to do well in the first place).

The essential function of challenging behavior is to communicate to adults that a kid doesn’t possess the skills to handle certain demands in certain situations.

This definition sets the stage for interventions aimed at solving the problems that are giving rise to challenging behavior and teaching the kid the skills he’s lacking.

So, back to the original question: What is the fate of the FBA? I can’t think of a reason to stop doing them. But if you want an FBA to help you get to the

core

of challenging behavior—lagging skills and unsolved problems—you’ll want to focus on the second pass rather than the first. By the way, you don’t need to do a full-blown FBA to complete the ALSUP and achieve a consensus on a kid’s lagging skills and unsolved problems.

Question:

I’m not quite clear about what you mean by “unsolved problems.” Can you explain further?

Answer:

Challenging kids aren’t challenging every minute. They’re challenging sometimes, under certain conditions, usually when the environment is demanding skills they aren’t able to muster or presenting problems they aren’t able to solve. As you’ve read, lagging skills are the

why

of challenging behavior. Unsolved problems are the

who, what, where,

and

when

of challenging behavior and help adults pinpoint the specific circumstances or conditions under which a kid’s challenging behavior is most likely to occur.

So if a kid is having difficulty in his interactions with a particular classmate (a “who”) or teacher (another “who”), and those interactions are setting the stage for challenging behavior, then getting along with that particular classmate or teacher is an unsolved problem. If a kid is having difficulties with a particular assignment (a “what”), and those difficulties are setting the stage for challenging behavior, then difficulty with that assignment is an unsolved problem. Difficulties on the school bus, in the cafeteria, or in the hallway (all “where” and “when”) are also unsolved problems. If the kid could resolve these problems in an adaptive manner, he would.

I use the terms “unsolved problems,” “triggers,” “circumstances,” “antecedents,” and “situations” interchangeably, but they all refer to the same thing. I like “unsolved problems” best, though, because it unambiguously tells us that there’s a problem the child is having difficulty solving on his own.

Question:

What research supports the idea that challenging behavior is a form of developmental delay?

Answer:

Much of the research is, for better or worse (mostly worse), tied to specific diagnoses, but the link between lagging skills and challenging behavior is unequivocal. For example, the association between ADHD and lagging executive skills (e.g., difficulty shifting cognitive set, doing things in a logical sequence, having a sense of time, maintaining focus, controlling one’s impulses) is well-established. Equally well-established is the fact that kids with ADHD are at increased risk for other diagnoses (and much more serious challenging behavior), such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD: temper outbursts, arguing with adults, and defiance) and conduct disorder (CD: bullying, threatening,

intimidating, fighting, physical aggression, stealing, destroying property, lying, truancy).

2