Lost Empire (26 page)

Authors: Clive;Grant Blackwood Cussler

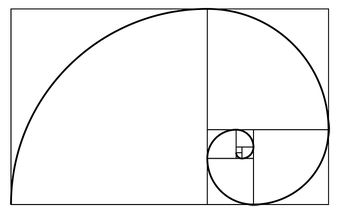

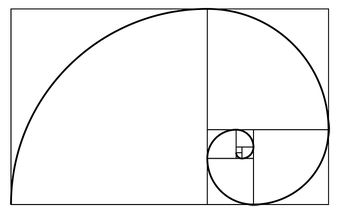

“You get the idea,” he said. “It’s also the basis of what’s known as the golden ratio, or the golden spiral, or even the Fibonacci spiral. Here, I’ll show you.” He walked to one of the computer workstations, did a quick Google search, and double-clicked a thumbnail. It filled the screen:

“You simply build a grid with whatever Fibonacci numbers you choose and overlay it with an arc,” Sam said. “Your first box could be an inch square or a foot square. Anything.”

“That’s what’s on the journal page,” Remi said. “A Fibonacci spiral.”

Sam nodded. “Part of one, at least. The spiral is central to a lot of sacred geometry theories. You see the spiral in nature—the way shells form, in the buds of flowers. The Greeks used the spiral in a lot of their architecture. Even Web designers and graphic artists use it to create layouts. There’ve been scientific studies that show the golden spiral is inherently pleasing to the eye. No one’s exactly sure why.”

“The question is,” Remi said, “why was Blaylock obsessed with it? What else can it be used for, Sam?”

“Anything to do with geometry, really. I read that the NSA uses the Fibonacci sequence and the spiral in cryptography, but don’t ask me how. That’s far outside my wheelhouse. Selma, are there any more images that repeat?”

In response, Selma picked up the phone and dialed the archive vault. “Pete, do you remember image twelve-alpha-four? Right, that’s the one. How many repeats so far? Have you digitized it yet? Good, put it on the server, will you? I want to show it to Mr. and Mrs. Fargo. I’ll hold.” A few moments later: “Thanks.”

Selma hung up, grabbed the remote, and used it to scroll back into the server’s file system. “The image we’ve named twelve-alpha-four has repeated nine times so far, usually in the margins but sometimes as a central image. Here it is. Wendy worked her magic and plucked it off the page. It’s still pretty messy.” On the screen, Selma moved the pointer over a thumbnail and double-clicked it. The image enlarged:

“Looks like a skull,” Sam said.

“My thought as well,” replied Selma.

Sam looked at Remi, who was staring at the image, her head cocked to one side, eyes narrowed. He said, “Remi . . . Remi . . .”

She blinked her eyes and looked at him. “Yes?”

“I know that expression. What’s happening in your head?”

She didn’t reply but shook her head absently. Without a word she got up, walked to one of the workstations, and sat down. Her fingers began working the keyboard. Without turning she said, “Just had a moment of déjà vu. Ever since we ran into Rivera and his men, their names have been stuck in my head. Why Aztec names? I thought it was just an oddity. I did a semester of Ancient Mesoamerican Studies at B.C., so I knew I’d seen that image before.” She tapped a few more keys and murmured, “There you are . . .”

She turned in her seat and pointed at the TV screen. “It’s called Miquiztli. In Nahuatl, the Aztec language, it represented death.”

CHAPTER 27

“THAT’S MORE THAN A LITTLE OMINOUS,” SAM SAID AFTER A moment.

“It also doubled as the symbol for the afterlife. It’s all about context. Selma, do we have others?”

“Yes, three.” Selma brought them up on screen:

Remi peered at them for a few moments, then said, “Do we have images we can use to compare?”

Selma picked up the phone to check.

Remi went on: “Unless I’m wrong, they’re all Aztec, too. The one on the right is Tecpatl, which represents flint, or obsidian knife; the middle one is Cipactli, or crocodile; the last one is Xochitl, or flower. It represents the last day of the twenty-day month.”

Sam asked Selma, “And these were isolated like the first one? No annotations?”

Selma was off the phone. “None. Wendy’s uploading some clean images onto the server now.” Selma used the pointer to back out of the current image files until she found the new ones.

They were labeled “Flint,” “Crocodile,” and “Flower”:

“They look like a match to me,” Selma said.

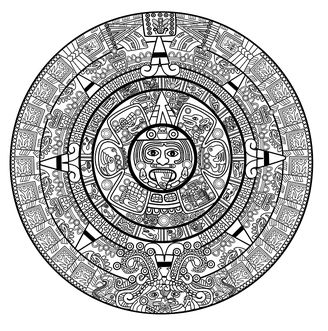

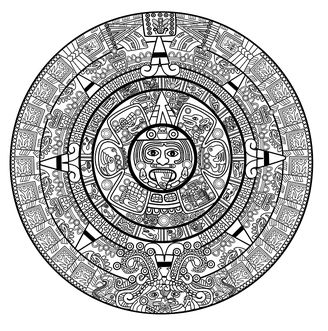

“Me too,” replied Sam. “Remi, all of these are from the Aztec calendar, correct? It might be useful to see the whole thing.”

“I have the one Remi downloaded for me,” Selma said. She scrolled around the screen, found the correct file, and double-clicked it:

“Now,

that’s

a calendar,” Sam muttered. “How in the hell did they make sense of that?”

that’s

a calendar,” Sam muttered. “How in the hell did they make sense of that?”

“Patience, I would imagine,” Remi replied. “The symbols we’ve found so far all belong to the month ring. It’s the fourth one from the edge.”

“No wonder the one in Mexico City’s so big. How big exactly?”

“Twelve feet in diameter and four feet thick.”

“It’d have to be that big for anything to stand out. It’s fascinating.”

“More so when you realize it’s over five hundred years old. Three hundred of those it spent buried under the main square. Workers found it while doing repair work on the cathedral. It’s one of the last vestiges of Aztec culture.”

The three of them went silent.

Selma’s cell phone rang. She answered, listened, then said, “We’ll be here. Bring it to the side gate. I’ll have Pete meet you.” She disconnected and told Sam and Remi, “Dobo’s on his way with the bell.”

“That was fast,” said Remi.

“Feels like Christmas morning,” Sam replied.

TWENTY MINUTES LATER Pete Jeffcoat and Dobo came through the workroom’s side door, one pushing and the other pulling a chest-high wheeled enclosure constructed of two-by-fours; hanging inside it was the

Shenandoah

’s bell. Aside from a few darkened patches, the tarnish and barnacles were gone, swept away by Dobo’s magic. The bronze exterior fairly glowed under the workroom’s halogen pendant lights.

Shenandoah

’s bell. Aside from a few darkened patches, the tarnish and barnacles were gone, swept away by Dobo’s magic. The bronze exterior fairly glowed under the workroom’s halogen pendant lights.

Standing arms akimbo in his denim coveralls and white T-shirt, Dobo surveyed his handiwork. “Nice, yes?”

“Beautiful work, Dobo,” said Sam.

If not for his frequent and easy smiles, Alexandru Dobo would have looked sinister, with his bald pate and thick, drooping mustache. He was, Remi had once observed, a Cossack lost in time.

“Thank you, my friend.” He clapped Sam on the back. Sam took a steadying step, then one more—away from Dobo. “You see inside?” the Romanian asked. “See inside! Pyotr, help.”

Dobo and Pete unlatched the bell from its hook, lifted it free, turned it upside down, then returned it, mouth up, to the cage. “Look, look!”

Sam, Remi, and Selma stepped forward and peered into the bell’s interior. Remi sighed. After a few moments Sam said, “Wish I could say I was surprised.”

“Me too,” replied Remi.

Carved haphazardly into the bell’s bronze interior were dozens, perhaps hundreds, of what appeared to be Aztec symbols.

After a few moments Sam muttered, “All aboard the Blaylock crazy train.”

SAM AND REMI GATHERED their team around the worktable, and over the next few hours, and a pair of family-sized pies from Sammy’s Wood-fired Pizzas, they mulled over the mystery before them. The crux of the issue, they decided, could be summed up in two questions:

1. Did Blaylock’s apparent mental instability cast into doubt all they’d found?

2. Were Rivera and his people on a fool’s quest based on Blaylock’s influence, or on other evidence?

Clearly Rivera was either searching for something or trying to keep something hidden, something that was probably Aztec in origin.

Pete Jeffcoat said, “If you’re right about the tourists they murdered, then it seems clear they’re trying to hide something. It’s hard for me to believe they’d do that just because of Blaylock. Wouldn’t they have been asking the same questions about the guy that we are?”

“Good point,” Sam said.

“If that’s the case,” Wendy said, “then maybe Blaylock wasn’t insane; maybe he was just eccentric, and there was something to his Aztec obsession.”

“As well as his fixation on the ship,” Selma added.

Remi said, “Okay, let’s take that as a given. How and why we don’t know, but Blaylock became obsessed with the

Shenandoah

, or

El Majidi

; at some point after that, his mind turned to all things Aztec. Before we go any further, we need to find out when that happened and what caused it.”

Shenandoah

, or

El Majidi

; at some point after that, his mind turned to all things Aztec. Before we go any further, we need to find out when that happened and what caused it.”

Sam asked Pete and Wendy, “How’re we doing on Miss Cynthia’s letters?”

“Another hour or so, and we should have them all examined,” Wendy replied. “Another two hours to scan them and have the computer do an optical character recognition search. After that, we’ll be able to easily sort them by date and search by key word.”

Sam smiled. “Got any big plans tonight?”

“I guess we do now,” Pete replied.

ACCUSTOMED TO how her husband’s brain worked, Remi was not surprised to awaken and find him sitting up at the edge of the bed, Apple iPad propped on his knees. The nightstand clock read 4:12 A.M.

“Lightbulb moment?” she asked.

“I was thinking about chaos.”

“Of course you were.”

“And how most mathematicians don’t believe in it. They know it exists—there’s even chaos theory—but I think secretly they all believe in underlying order. Even if it’s not obvious.”

“I can buy that.”

“Then why would Blaylock go to all the trouble of randomly carving Aztec glyphs on the bell’s interior? And why the bell?”

Remi said, “I assume that’s a rhetorical question.”

“I’m working through it. Did you read this poem from Blaylock’s journal?”

“I didn’t know there was one.”

“I just found it. Pete and Wendy just uploaded it,” Sam said, then recited:

In my love’s heart I pen my devotion

On Engai’s gyrare I trust my feet

From above, the earth turns, my day is halved

Words of Ancients

words of Father Algarismo

On Engai’s gyrare I trust my feet

From above, the earth turns, my day is halved

Words of Ancients

words of Father Algarismo

“Not bad for a mathematician,” observed Remi.

“I wonder if he used the bell because it’s durable, unlike paper. I also wonder if he used it because of its shape.”

Other books

Murder of a Wedding Belle by Swanson, Denise

The Closers by Michael Connelly

Hallowed Bones by Carolyn Haines

Consider Phlebas by Banks, Iain M.

A Christmas Surprise by Downs, Lindsay

The Temptation of Lady Serena by Ella Quinn

Mistress of the Throne (The Mughal intrigues) by Ruchir, Gupta

Leaving: A Novel by Richard Dry

Echo of Tomorrow: Book Two (The Drake Chronicles) by Rob Buckman