Lost Empire (27 page)

Authors: Clive;Grant Blackwood Cussler

“You’ve lost me.”

“The first line of his poem—‘In my love’s heart I pen my devotion’—he’s got to be talking about his wife, about Ophelia, which is what he renamed the

El Majidi

.”

El Majidi

.”

Remi caught on. “And a ship’s bell could be considered the heart of the ship.”

“Right. Now, the second line, ‘On Engai’s gyrare I trust my feet.’ In Swahili,

Engai

is one of the spellings for the Maasai’s version of ‘God,’ and

gyrare

is Latin for ‘gyre’; it’s a synonym for vortex or spiral.”

Engai

is one of the spellings for the Maasai’s version of ‘God,’ and

gyrare

is Latin for ‘gyre’; it’s a synonym for vortex or spiral.”

“As in the Fibonacci spiral. God’s pattern in nature.”

“That’s what I was thinking. Blaylock was using the spiral to guide himself. Put the lines together and maybe you’ve got Blaylock inscribing the bell with the source of his devotion—his obsession—and using the Fibonacci spiral as some kind of encoding technique.”

“And since by the time he made the inscriptions his wife was dead and he’d found the

Shenandoah

, his ‘devotion’ was something else altogether,” said Remi. “What about the gyre? How exactly would that fit in?”

Shenandoah

, his ‘devotion’ was something else altogether,” said Remi. “What about the gyre? How exactly would that fit in?”

“Picture a golden spiral.”

“Okay.”

“Now picture it superimposed on the interior of the bell, starting at the crown and spiraling downward and outward toward the mouth.”

Remi was nodding. “And wherever the spiral intersects a symbol it means . . .” She shrugged. “What?”

“I don’t know. Something to do with the last three lines of the poem, maybe. I’m still working on that. All I know is that two of the most frequently repeated items in his journal are the Fibonacci spiral and Aztec symbols. If he’s hiding something, they’re probably involved.”

THEY GOT UP, made a carafe of coffee, and headed down to the workroom. Selma was asleep on a cot in the corner. The overhead halogen lights were dimmed. Pete and Wendy sat at the worktable, laptops open, the screens’ glow illuminating their faces.

“Coffee, guys?” Sam whispered.

Wendy smiled, shook her head, and nodded toward the collection of Red Bull cans on the table.

“We’re almost done,” Pete said. “Those Ziploc bags must have done the trick. It’s just a guess, but I’d say the letters have been protected in one way or another for most of their life.”

“You got them all?” Remi asked.

Wendy nodded. “Aside from some illegible spots here and there. We’ll have everything uploaded and sorted in a couple hours.”

“Sam’s got a hunch he wants to play,” Remi said.

“We’re all ears,” replied Wendy.

Sam explained his theory. Pete and Wendy considered it for a few moments, then nodded in unison. “Plausible,” Pete said.

“Ditto,” Wendy added. “Blaylock was a mathematician. Those guys love order within chaos.”

From across the room Selma’s scratchy voice said, “Buy what?”

“Go back to sleep,” Remi said.

“Too late. I’m up. Buy what?”

She got off the cot and shuffled to the worktable. Remi poured her a cup of coffee and slid the mug down the table. Selma palmed it, took a sip. Sam reexplained his spiral/bell/symbol theory.

“It’s worth a shot,” Selma agreed. “The crown of the bell would be the likely place to start the spiral, but how do we know how big it is? And you’re assuming it would unravel and end at the bell’s mouth. What if it doesn’t?”

Sam smiled wearily. “Killjoy.”

THE GROUP BEGAN BRAINSTORMING. At the top of their list was the question of scale. A Fibonacci spiral could be built to any scale. If Blaylock was in fact using a spiral, he would’ve used a reference size for the first box in the grid. They tossed around ideas for an hour before realizing they were getting nowhere.

“It could be anything,” Sam said, rubbing his eyes. “A number, a note, a doodle . . .”

“Or something we haven’t even seen yet,” Remi added. “Something we’ve overlooked.”

Across the table, an exhausted Pete Jeffcoat laid his head down on the wood and stretched his arms before him. His right hand struck Blaylock’s walking staff, which rolled off the edge and clattered to the floor.

“Damn!” Pete said. “Sorry.”

“No problem.” Sam knelt down to retrieve the staff. The bell clapper had torn free of its leather bindings and was hanging by a single thong. Sam picked them up together. He stopped and peered at the head of the staff. He frowned.

“Sam?” said Remi.

“I need a flashlight.”

Wendy pulled out a storage drawer and handed an LED across to Sam, who clicked it on and shone it onto the staff’s head. “It’s hollow,” he muttered. “I need some long-handled tweezers.”

Wendy retrieved a pair, handed them over.

Gingerly, Sam inserted the tips of the tweezers into the opening, wriggled them around for a few seconds, then began withdrawing them.

Grasped between the pincers was a corner of parchment.

CHAPTER 28

“OH, SURE,” SAM MUTTERED. “IT COULDN’T HAVE BEEN SOMETHING easy. Like a map with a big X on it.”

Wary of damaging the remainder of the parchment, or anything else that might lie hidden inside Blaylock’s walking staff, Pete and Wendy had taken it into the archive vault for extraction and triage preservation.

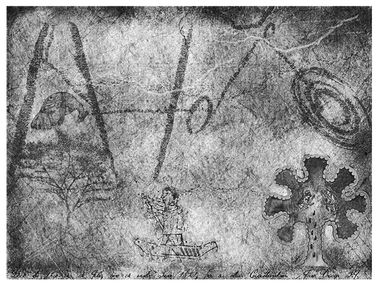

Ten minutes later a digital image of what Sam had grabbed with his tweezers appeared on the workroom’s LCD screen:

Pete came out of the vault. He said, “We had to reduce it. The map’s actual dimensions are roughly six inches wide by ten long.”

“What about those notations along the coast?” Sam asked.

“Once we get the map digitized, Wendy’s going to work her Photoshop magic and try to clean them up. Based on their placement and the capital

R

suffix, they’re probably river names—in French, by the looks of it. The partial word in the upper left-hand corner—‘runes’—might be something we can work with, too.

R

suffix, they’re probably river names—in French, by the looks of it. The partial word in the upper left-hand corner—‘runes’—might be something we can work with, too.

“There’s another notation,” Pete continued. “See the arrow I superimposed?”

“Yes,” Remi replied.

“There’s some microwriting overtop that little island. We’re working on that as well.”

The archive vault door opened, and Wendy emerged carrying a rectangle of parchment sandwiched between two panes of Lexan clear polycarbonate.

“What’s this?” Remi asked.

“The surprise behind door number two,” replied Wendy. “This was rolled up at the bottom of the staff.”

She laid the pane on the worktable.

Sam, Remi, and Selma gathered around it and stared in silence for ten seconds.

Finally Remi whispered, “It’s a codex. An Aztec codex.”

FACED WITH two seemingly disparate artifacts, they divided forces. Pete and Wendy settled down at a workstation to identify the map, while Sam, Remi, and Selma tackled this new parchment.

Remi began. “Codex is Latin for a ‘block of wood,’ but over time it became synonymous with any type of bound book or parchment. It’s the model for modern book manufacturing, but before binding became common practice anything could be considered a codex—even a single piece of parchment or several folded together.

“You see, when the Spanish invaded Mexico in 1519—”

Sam interrupted. “Maybe now would be a good time for an Aztec 101 course?”

“Okay. Bear in mind, among historians there’s a lot of debate about the Aztecs, from the trivial to the significant. I’ll give you the condensed, middle-of-the road version.

“Aztec is the popular name for a group of Nahua-speaking peoples that some historians refer to as the Mexica—sounds like Meh-SHEE-kah—who migrated into central Mexico from somewhere to the north in the sixth century.”

“‘Somewhere to the north’ is rather vague,” Selma observed.

Remi nodded. “Yet another source of controversy. I’ll cover that in a minute. So the Aztecs continued their migration into the Valley of Mexico, displacing and absorbing other tribes—including some of their mythology and cultural practices. This went on until around the twelfth century. At the time, most of the power in the region was concentrated in the hands of the Tepanecs in Azcapotzalco. Fast-forward: power trades hands, alliances are made and broken, and the Aztecs are fairly low on the power ladder.

“Until 1323, when legend has it that the Aztecs were shown a vision of an eagle with a snake in its mouth perched atop a cactus. After a few more years of wandering, the Aztecs come across a swampy, barely inhabitable island in the middle of Lake Texcoco—which is mostly gone today; it sits beneath Mexico City. It’s on this island they supposedly see the eagle/snake/cactus vision. They stop wandering and start building. They called their new city Tenochtitlán.

“Despite their new capital being as much marsh as it was land, the Aztecs pulled off an engineering marvel. Tenochtitlán occupied about five square miles on the west side of Lake Texcoco. They built causeways to the mainland, complete with rising bridges to accommodate water traffic; they built aqueducts to supply the city with fresh water; there were plazas and palaces, residential areas, and business centers all connected by canals. When the population got too big to feed with crops grown on the mainland, Aztec engineers created floating gardens called

chinampas

that could produce up to seven crops a year.

chinampas

that could produce up to seven crops a year.

“This went on another fifty years or so until the late 1420s, when the Triple Alliance among Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tlacopan was formed. All the tribes outside the alliance were subjugated as the alliance grew in strength. Then, slowly, over the next century, the Aztecs and Tenochtitlán rose to the top.”

“And then Cortés arrived,” Sam said.

“Right. In the spring of 1519. Within two years, the Aztec Empire was all but destroyed.”

“What’s the rest of the controversy?” Selma said. “About the Aztecs?”

“Where they came from—north or south, or from how far away. Many of the classical and pre-classical Mesoamerican cultures—the Toltecs, the Maya, the Olmecs—share similarities with the Aztecs. It’s a chicken-or-egg situation. Was it simply a matter of cultural cross-pollination or was one of these peoples the precursor to all the rest? There are a lot of historians who think the Aztecs were Mesoamerica’s true progenitors.”

Sam and Selma took all this in. Then Sam said, “Okay, you were talking about codices . . .”

“Right,” Remi said. “When Cortés invaded and the Aztec Empire collapsed, there were a lot of codices written, most of them by Jesuit and Franciscan monks, some by soldiers or diplomats, and even a few by Aztecs as dictated to others. Those are fairly rare and usually discounted—or at least they were until the last couple hundred years. Aztec codices tended to stray from the Spanish ‘party line,’ which was that Aztecs were savages and that their conquest was wonderful and dictated by God. You get the idea.”

“Again, victors write the history,” Sam said.

“You got it.”

Selma said, “You’re talking about the Codex Borbonicus, the Mendoza, the Florentine . . .”

“Right. There are dozens. Usually they depict Aztec life either before, during, or after the Spanish conquest. Some are just tableaus of routine activities while others are meant as historical accounts of Cortés’s arrival, of battles fought or ceremonies, and so on.”

Other books

The Avenger 17 - Nevlo by Kenneth Robeson

Speedboat by RENATA ADLER

Highland Son (Highland Sorcery: A New Dawn) by Clover Autrey

The Magician's Apprentice by Canavan, Trudi

The Scrubs by Simon Janus

The Alaskan by Curwood, James Oliver

The Man-Kzin Wars 01 by Larry Niven

Mr. Nice Spy by Jordan McCollum

Gracie's Game: Sudden Anger, Accidentally on Purpose by Parker, Jack

Traitor by Julia Sykes