Louis S. Warren (84 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

Midpage, between the two images, is a telling poem, “Lines Inspired on Witnessing the Prairie Chief Caressing His Baby Daughter, Little Irma Cody”:

Only a baby's fingers patting a brawny cheek,

Only a laughing dimple in the chin so soft and sleek,

Only a cooing babble, only a frightened tear,

But it makes a man both brave and kind

To have them ever near.

The hand that seemed so harsh and cruel,

Nerved by a righteous hate

As it cleft the heart of Yellow Hand,

In revenge of Custer's fate,

Has the tender touch of a woman,

As rifle and knife laid by,

He coos and tosses the baby,

Darling “apple of his eye.”

Thus the prairie centaur featured in the top illustration, the vengeful slayer of “Yellow Hand,” has been domesticated by the daughterâand the wife who provided herâin the bottom image. In a limited way, the frontier hero has become a paragon of the new, suburban “masculine domesticity,” which situated men in closer proximity to family and home than in previous generations.

11

So audiences were astonished to read in major newspapers, in the early months of 1904, that after thirty-eight years of marriage, Buffalo Bill Cody was suing his wife for divorce. The family, however, was not surprised. The 1890s had been no kinder to the Cody marriage than any of the previous decades. In 1893, while he was showing in Chicago, Louisa made a surprise visit to the house where she had heard that he was living with Katherine Clemmons. She did not find Clemmons. Louisa tore the place to pieces. Upon her return to North Platte, she told her staff, “I cleaned out the house.”

12

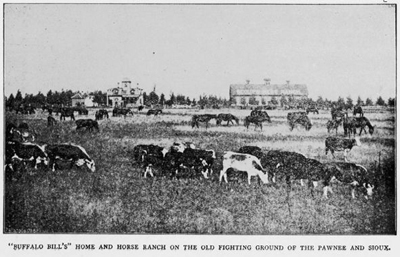

Cody's image hinged on his being a domesticator of the frontier (top) through

the establishment of the family home (bottom), particularly at the Scout's Rest

Ranchâwhere Louisa refused to live. Buffalo Bill's Wild West

1893

Program,

author's collection.

In 1898, she went to New York and took a room at the Astoria. She called her husband at the Hoffman House, where the phone was answered by a press agent named Bess Isbell. This time, she upended her own room, and William Cody paid the bill.

13

Mistresses aside, their most constant bone of contention was his Scout's Rest Ranch, over which she struggled to gain control, although she refused to live in it. Under pressure from Louisa, William Cody's sister Julia and her husband, Al Goodman, had vacated the premises in 1891, so that Arta and her husband, Horton Boal, could manage the property. Although Goodman returned to manage it again in 1894, he left for good in 1899.

14

Goodman and the other managers and foremen of the ranch took their orders from William Cody, but all of them complained of interference, even hostility, from his wife, who constantly countermanded Cody's orders and imposed demands of her own. As time passed, there may have been confusion about who was in charge. William Cody corresponded with ranch managers and continued to give them advice about how to handle the ranch. “I sent out . . . one of my old dining room tents,” he wrote one of them, “to cover the [hay]stacks with . . . to keep the exposed stack from getting wet.”

15

He advised them on confrontations with Louisa right up to the time he filed the divorce petition. But in 1900, soon after Al Goodman left, he handed the ranch over to Louisa with a one-line, unpunctuated message: “The ranch is yours take it run it to suit yourself.”

16

He returned home to North Platte for a brief Christmas break in 1901. After that, he ceased his visits to the town or to Louisa.

17

William Cody's petition for divorce rested on two complaints. First, he made the stunning accusation that Louisa had many times threatened to poison him. Second, and more banal, was the charge that she had driven him “from his former home in North Platte, Nebraska, and has at divers times refused” to let him “bring his friends and guests” to that home. At times when he did, Louisa “would make it so unpleasant for him and his guests they were forced to leave.” His married life was “unbearable and intolerable” in these conditions.

18

The nation's newspapers quickly cast the drama as a tongue-in-cheek Wild West show. “Intrenched in a legal fastness and surrounded by a band of brave attorneys, who know every byepath [

sic

] of the Wyoming divorce laws, the hero of the thrillers of two generations started today to fight his way to marital freedom,” wrote one reporter. On the other side, “Mrs. Cody, surrounded by another brave band of attorneys, is determined to fight to the last ditch, for she asserts the colonel wants the divorce only in order to marry another woman.”

19

The newspaper narrative turned the celebrity divorce trial into entertainment. But understanding how William Cody understood his marriage and his life, and why he lost this case, requires examining a very different story. The divorce trial was in a sense a battle of narratives, and William Cody's charges told a familiar and popular tale. For all the tensions over money and property that checkered their marriage, the heart of his case was the sensational allegation of the poison threat. Wild West show programs had long scripted Buffalo Bill's home, especially Scout's Rest Ranch, as the domesticated triumph of the frontiersman. The poison charge emplotted both Codys into a quite different drama, one in which an evil woman lured her husband to provide home and wealth, and then poisoned him to gain control of the property.

This was, indeed, the plot of

Lucretia Borgia,

a popular melodrama in the nineteenth century, and one which so appealed to William Cody that by the late 1860s he had named his favorite buffalo rifle after the treacherous title character. Whether or not he was aware of the similarities between his accusations and the play, the old showman's complaint resonated with the dark side of the domestic dream, the nightmare of the deceiving woman who strikes out from the heart of the home where the man believes he is safest. As various scholars have observed, this narrative is a mythic trope as old as the home itself, and a powerful undercurrent running against the popular enthusiasm for home and domesticity in the late nineteenth century.

20

William Cody's first attempt at divorce, more than twenty years before, had halted when little Orra Cody suddenly died. Nothing would stop this one from proceeding, but the couple's bitterness was compounded by another tragedy. Weeks after William Cody filed the petition, daughter Arta suddenly died of “organic trouble.” Her life had become a tragedy in itself. Her first husband, Horton Boal, committed suicide in 1902, leaving her with two infant children. She remarried in January 1904, at a small Denver wedding which her father attended. Her new husband, Dr. Charles Thorp, worked as a surgeon for the Northern Pacific railroad. But within a month, she was dead.

21

With the heartbroken parents locked in a court battle, the funeral was a disaster. Upon hearing of Arta's sudden death, William Cody sent a telegram to Louisa, asking to put “personal differences” aside while they buried their daughter.

22

Louisa herself may have been attempting a reconciliation at the time Arta died. Arta's two children had been visiting Louisa when Arta sent word that she was very ill and was about to have surgery, from which she did not expect to recover. Louisa and the children immediately began journeying to Arta's home in Spokane. She had resented the Cody sisters for many years, but in Denver she asked her husband's youngest sister, May Cody Bradford, to come along and help her, and she may have intended the invitation as a gesture to her husband.

But now, at the Bradford house in Denver, devastated by the telegram announcing Arta's death, Louisa was further hurt and infuriated by her husband's message. She refused to reconcile merely for the duration of the funeral. According to May Cody Bradford, she wanted to send a telegram accusing William Cody of murdering their daughter by breaking her heart with the divorce petition. Relatives persuaded her to soften her language.

23

William Cody, on his way to meet the family funeral procession in Omaha, received a message telling him his wife believed he “broke Arta's heart. Suit entered under false accusation.” Louisa would accept no temporary reconciliation. “Never for only a while, forever or not at all.”

24

The couple met in Omaha and did not speak, as they made their way with Arta's body to Chicago and on to its last resting place in Rochester, New York. The procession was tearful and tense. They rode in separate rooms of the sleeper car. As it became clear he would not attempt a reconciliation with her, Louisa threatened to “denounce him as Arta's murderer from the grave of his dead child.”

25

But she was silent as she put her first daughter in the ground, beside the graves of Kit and Orra Cody. At the conclusion of the funeral, William Cody left for New York City. As he left, he turned to his old friend Frank Powell and asked him to see if Louisa was open to a reconciliation. According to Powell, a man for whom Louisa had only contempt, she refused. She made her way back to Nebraska, still accompanied by her sister-in-law. Stopping over in Chicago, she raged at William Cody, shook her fist at his sister, and swore, “I will bring you Codys down so low the dogs won't bark at you.”

26

The divorce trial did not begin until almost a year after Arta's death, by which time William Cody had added two more complaints to his petition. The first was that Louisa refused to sign mortgages, which made it impossible for him to carry on his business. The final charge was that she had subjected him to “extreme cruelty” in charging him with Arta Cody's murder.

27

Testimony was made in depositions, many of them in open court in Cheyenne, before an audience of some three hundred “women, cowboys, and officers from Fort Russell,” according to the press.

28

At the close of proceedings, the judge would render his decision.

The opening testimony by William Cody was actually made in a deposition the year before, in which he told the court of his long, unhappy marriage to Louisaâof his fights with her from their earliest days, his venture to “the end of the line” to escape his unhappy home, her discontent with his buffalo hunting and her disappointment in him upon the failure of his town of Rome. She disliked his life in the theater, was jealous of friendly actresses, and was always critical of him. “My home was made disagreeable to such an extent that I am ashamed to say . . . that I chose the saloons and the wine cup at times in preference.”

29

In recent years, matters had become worse. “Well, kiss it goodbye, that's gone,” she taunted him every time she signed a mortgage to provide cash for the Wild West show. Finally, she “refused to sign her name to any piece of paper at all for me.” He had outstanding mortgages he could not pay, and other properties he needed to sell. But “as she will not sign any papers, I find myself unable to conduct my affairs in a businesslike manner.”

30